Divergent Economic and Ideological Visions Contend Ahead of 20th Party Congress

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 12

By:

Introduction

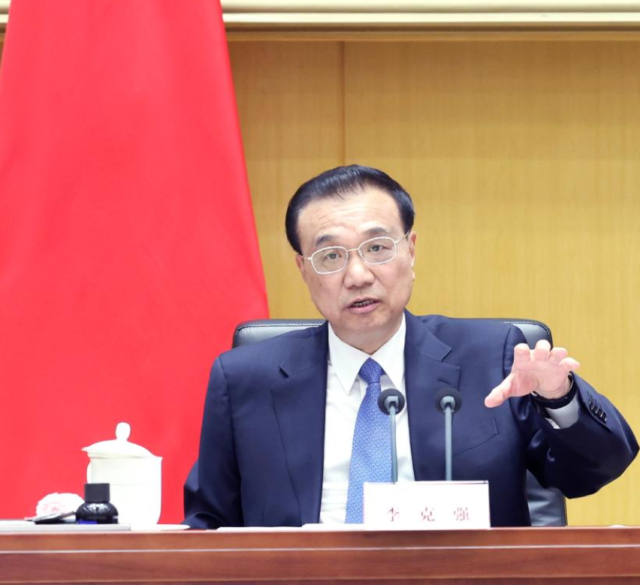

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) approaches its 20th National Congress, the economic downturn in China has opened a Pandora’s Box of theoretical debates on how to manage this crisis. Premier Li Keqiang recently suggested that the nation’s economic performance has been weak and may not meet its GDP growth targets as the problems facing the economy are more serious than they were in 2020 (Gov.cn, May 26). In China’s political arena, theoretical discussions have always been key to guiding the country’s future development, especially at a time of social and economic disruption. This dynamic is particularly marked at present in light of the recent revelation about a possible policy divergence between General Secretary Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang over China’s future economic development model. While the principal contradiction remains unchanged, the questions of how to deliver common prosperity and how to manage policy direction, defined seven years ago, remain unanswered.

Xi’s Way of Seeing Contradictions

The concept of contradictions (矛盾, maodun ) is embedded in the CCP’s rhetorical foundation and plays an important part in China’s domestic theoretical debates. Furthermore, Marxist doctrine, which the Party follows, states that only by identifying and solving the “general contradiction” can a society peacefully develop, while failure to do so will push society toward chaos and revolution. In the history of the CCP, this discussion started with Mao’s paper “On contradiction” (August 1937), and twenty years later, his writing “On the correct handling of contradictions among the people” (February 1957). [1] Verbs that connotate conflicts, such as fight and struggle (斗争, douzheng) occur frequently in party documents. In the Maoist period, this was reflected in the party’s intense focus on class contradictions that sparked the modern Chinese revolution, as well as a three-sided conflict between imperialism, feudalism, and the Chinese nation that constituted a modern society.

In contrast to the Maoist era, under Deng Xiaoping, the CCP focused less on the contradictions between the working class and the bourgeoisie, and instead saw capital as a vehicle for generating material well-being. The reasoning of “the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people” prevailed and allowed Deng to conduct his policy of reform and opening up (People.cn, October 24, 2017). However, nothing lasts forever, and Xi’s tenure started with a redefinition of domestic contradictions. Xi has summarized all of the past contradictions, considers them fulfilled, and has now established a new one – unbalanced development and the people’s need for “a better life” (美好生活, meihao shenghuo) (Xinhuanet, October 24. 2017). “What we now face is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life,” Xi said in his 19th Party Congress report (Gov.cn, November 3, 2017). In order to achieve what it sees as a better outcome for the Chinese population, the CCP has set its goals for a “people-centric philosophy of development” and common prosperity. In this way, the party not only creates new narratives and alters political discourse, but also presents itself as an institution that takes care of its citizens and their changing needs. However, Mao stated in 1957 that in peaceful times and “ordinary circumstances, contradictions among the people are not antagonistic.” [2] As China now faces an economic downturn that may lead to social turmoil, the question of resolving contradictions among the people is apparently at the top of Beijing’s agenda.

Can Common Prosperity be achieved through Introverted Institutional Changes?

Five years ago, Xi declared that China had entered five sub-eras under the New Era that marked the new leadership period in China’s history. The sub-eras are an era of securing a great victory, an era of building a great modern socialist country in all respects, an era of achieving common prosperity for everyone, an era of realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, and an era of moving to the center on the world stage. However, in order to achieve common prosperity and the status of a modern socialist country, existing contradictions among the people need to be effectively managed (Gov.cn, November 27, 2017).

In order to realize common prosperity, Gong Yun, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, reiterated Xi Jinping’s thoughts in the CCP’s theoretical journal- Qiushi (Seeking Truth). Per Gong, Xi’s emphasis on greater party involvement in the nation’s economy is central: “the party must adhere to the basic economic system, unswervingly consolidate and develop the public ownership economy, and unswervingly encourage, support, and guide the healthy development of the non-public ownership economy to play an active role in the process of realizing common prosperity” (Qiushi, March 25; Qiushi, October 24, 2019). From a general perspective, this centralization model ensures effective management of contradictions in society. This approach is exemplified by the anti-corruption campaign, and the crackdown against the technology industry with Alibaba founder Jack Ma serving as the symbol for “individualistic” and “capitalistic” paths. The central government’s intervention in the economy is also evident in Xi’s recent announcement of major infrastructure projects, which will invariably be largely undertaken by state-owned enterprises (Xinhua, April 27).

Apart from this ongoing overall centralization, what is less known is the institutional dimension of lead CCP theorist and Politburo Standing Committee member Wang Huning’s approach, which is evidenced throughout the country in the form of mediation centers (矛调中心, maodiao zhongxin). In June 2021, the Central Committee and the State Council issued a special document on Zhejiang province’s pilot demonstration zone for common prosperity based on the mediation centers at the county level (Gov.cn, June 10, 2021). Data analysis from the China Academic Journal Database illustrates that Zhejiang has taken the lead in reforming institutions responsible for appeasing public tensions. This should come as no surprise as Zhejiang, in particular its capital city Hangzhou, is regarded as a national leader in social innovation.

An example of a mediation center, reported by the National Public Complaints and Proposals Administration (NPCP) can be found in the city of Ruian in Zhejiang province. According to Yu Liequan, executive deputy secretary of the Ruian Political and Legal Committee, as soon as the Mediation Centre opened it began to resolve disputes between citizens. Since 2020, the mediation center has resolved 1,830 cases of various contradictions and disputes, which according to local authorities, has brought about common prosperity wherever it is possible. It is also notable that local authorities stated that Ruian has always adhered to and followed people-centered policies and promised that the mediation center is the perfect solution to keep contradictions under control and to manage social stability and resolve disputes among people (NPCP, January 19, 2021).

Can Common Prosperity be Achieved by Keeping the Door Open?

As Deng’s definition of domestic contradictions aligned with his policy of reform and opening up, the current definition of contradiction has illuminated possible future scenarios for how to balance growing domestic contradictions and interdependence with the outside world. As the central leadership has continuously signaled, the global economic structure is experiencing what the CCP sees as structural and institutional disruption, typified by unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable development. As a remedy for these challenges, CCP leaders have promoted, especially to international audiences, global trade and investment liberalization. For example at this year’s World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Xi advocated liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment, developing a global network of the free trade zone, e.g. with the Hainan Free Trade Port, the promotion of institutional opening up of rules, regulations, management, as well as standards, and pledged to develop a larger and more comprehensive opening-up approach (WEF YouTube, January 17).

However, what looks good on paper may be more difficult to implement in reality. With this in mind, the CCP is seeking a third way. In the past, the policy of isolation has led to escalating tension as well as competition between local authorities for limited resources. How far along plans are for compulsory self-isolation of key economic sectors is debatable. It is puzzling that Premier Li, who is still responsible for economic development, assured the assembled press at the last Chinese National People’s Congress that no one “wants or can close the door” to the world (State Council, March 11). In contrast, Xi seemed to question the policy of “opening up” in a virtual meeting with U.S. President Joseph Biden, saying that “the prevailing trend of peace and development is facing serious challenges. The world is neither tranquil nor stable” (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, March 19).

Since March, People’s Daily– the party mouthpiece in which official positions are disseminated to domestic and global audiences, has presented two different views. On the one hand, the paper runs editorials characterized by intense anti-Americanism, which are no doubt supported by Beijing hardliners. However, its pages have also included more conciliatory viewpoints advocating for an open China that is part of the global economy. The former view, which is often espoused through the commentary of the “China voice” (钟声, zhongsheng) penname, has accused the United States of being an imperialistic hegemon, and a troublemaker in international security affairs, which has a detrimental impact on global stability and development. The war in Ukraine is also seen as part of, what hardliners assert are a pattern of hegemonic actions by the U.S. However, these anti-American sentiments in People’s Daily are countered by other perspectives that still cherish Deng’s “reform and opening up” and who adopt a fairly positive image of the European Union, and its member states. Even more significantly, a recent commentary entitled “Voice of harmony” (和音, heyin) likened China’s economy to a big ocean for all and praised global trade’s interdependence calling for more remain openness and inclusivity as had occurred previously under Deng (People’s Daily, March 1; March 7).

It is notable that after Premier Li hosted a video meeting with 100,000 cadres that focused on the economy, People’s Daily published an article under the series “Face to Face with the Party at 100” (百年大党面对面, bainian dadang mian dui mian) entitled “How is reform, opening up, and socialist modernization being carried out? (People’s Daily, May 27; Caixin, March 25). Interestingly, the article fails to mention Xi as core leader and exclusively discusses Deng’s approaches to reform and opening. The article also begins with a big bang question: “What is socialism?” Between the lines, the article defines China’s stage of development as being in the initial stage of socialism and warns against seeing China as a soon-to-be communist country.

Afraid of repeating the past mistakes of the Great Leap Forward, People’s Daily admitted that Chinese society is already socialist, although socialism in China is still in its infancy. Another striking aspect of the article was its proposed solution to the dilemma of how to deliver common prosperity arguing that “the essence of socialism is to liberate the productive forces, develop the productive forces, eliminate exploitation, eliminate polarization, and ultimately achieve common prosperity.” This statement goes against the centralization process that is in progress under Xi, and instead praises Deng’s economic decentralization that for bringing so many benefits to China over the last 40 years. The opinion piece went on to urge the party-state not to intervene in the economy, while shaping the political control in the party, and to follow the previous path of development with the “four cardinal principles” (The Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, March 30, 1979). The article stated that “some things must be changed and not changed, and some things must not be changed and cannot be changed, and if they are changed, they will lose their roots and lose their direction”.

What is even more striking about the May 27 People’s Daily article on reform and opening is its reference to former leader Jiang Zemin’s “theory of three represents” (三个代表, san ge daibiao), which gave businesspeople a voice in the economic reforms taking place within the party (People’s Daily, May 27). Moreover, the article stresses support for close relations with the outside world and active participation in the international community based on Deng Xiaoping’s “peace and development” approach. It is also noteworthy that the article quotes philosopher Wang Anshi (1021-1086) who advocated for reforms during the Northern Song dynasty. As is commonly known, the reforms that Wang Anshi proposed created political tension between his faction, which was known as the reformers, and conservative ministers led by historian and Chancellor Sima Guang (1019–1086). In other words, the May 27 Peoples’ Daily article gave voice to the opinion of technocrats aligned with Premier Li.

Conclusion

In the eyes of CCP leaders, a proper understanding and definition of contradictions is essential to securing the party’s political position and ensuring stability in the country. Certainly, a consensus exists that the government should be a guarantor of common prosperity. However, when it comes to determining optimal methods to implement this approach, the debate is far from over. Watching the domestic discussions there are two camps that are ready to do battle. The first group is the more anti-globalist movement, which is driven by anti-American sentiment and whose preferred way forward is to manage the domestic contradiction behind a closed door with a strict zero-COVID policy. In the opposite corner is an internationalist-oriented group, which hopes to keep China’s door open or at least ajar. Should the first group emerge from the 20th Party Congress in the driver’s seat it may seek to explain away policy deficiencies by utilizing anti-foreign rhetoric that portrays China as a besieged fortress with the ultimate goal of securing Xi’s central position. The “open-door” group, which prefers collective leadership, while also proactively managing an economic downturn and de-globalization, sees China as part of global value chains and a member of the international economic community. As far as China’s economic stance is concerned, the die is not yet cast.

Dominik Mierzejewski: head of the Centre for Asian Affairs (University of Lodz); Professor at Department of Asian Studies at the Faculty of International and Political Studies (University of Lodz); Chinese language studies at Shanghai International Studies University; visiting professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing; the principal investigator in grants supported by the National Science Centre (Poland), Horizon 2020, Ministry of Foreign Affairs; specializes in the rhetoric of Chinese diplomacy, political transformation of the PRC and the role of provinces in Chinese foreign policy.

Notes

[1] Mao Tse-tung, “On Contradiction,” Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Foreign Languages Press” (Peking, 1967), Vol. I, https://cmpa.io/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/02/MAO-ON-CONTRADICTION.pdf

[2] Mao Tse-tung, “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People,” February 27, 1957, Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung: Vol. V, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-5/mswv5_58.htm