Drought Threatens Ukraine, Its Relations with Russia, and Regional Cooperation Plans

Drought Threatens Ukraine, Its Relations with Russia, and Regional Cooperation Plans

Water levels in Ukraine’s rivers and reservoirs are the lowest they have ever been since records began to be kept in 1885, threatening the health and well-being of Ukrainians and the incomes of Ukrainian industry and the government (Dsnews.ua, April 30; see EDM, June 1), exacerbating tensions with Russia over water supplies for occupied Crimea (see EDM, May 21), and casting doubt on hopes for broader regional economic and political cooperation based on the development of a north-south waterway from the Black Sea to the Baltic (see EDM, April 28, May 13).

Because the declines in levels of both reservoirs and rivers have been so severe, Ukrainian officials and commentators have begun talking more about the issue. But resources at the country’s command, continuing problems with bureaucratic confusion, systemic corruption, and speculation about food prices have led some observers to conclude that Kyiv’s efforts may prove too little too late and harm Ukraine far more than anyone in the Volodymyr Zelenskyy administration seems to appreciate. It is an issue few outsiders have, to date, given much attention to, except for the implications in occupied Crimea. However, if these aforementioned experts are right, the severe widespread drought may play an increasing role in the future of Ukraine, the fate of its population, as well as relations with Ukrainian neighbors both to the east and to the north and west.

Ukraine has been facing drought for several years, with water shortages already pushing down food production (Dsnews.ua, June 15, 2018). But this season, according to Kyiv commentator Denis Lavnikevich, the situation has deteriorated markedly because of already lower water tables, river flows and reservoir reserves as well as a winter with far less precipitation than normal. Rains at the end of April were welcome—in Kyiv itself, they amounted to a one-day record that had previously stood for 129 years. But they did not cover all of Ukraine or seriously reduce the country’s water shortages. And by themselves, the April–May rainstorms will not ensure that Ukraine can continue to export as much grain as it has—40 percent of the country’s foreign trade earnings come from food exports—unless it allows prices to rise dangerously at home (Dsnews.ua, April 30).

Consumer advocates and agricultural producers are worried and have urged limits on exports (Agroportal.ua, accessed June 2), but most exporters and government officials do not want to sacrifice foreign hard currency earnings, especially given that there are already serious food shortage problems in other countries that will likely be looking to Ukraine for supplies. This is a position United Nations officials are stressing as well (Facebook.com/Alissitsa, April 13). Lavkinevich asserts that the choices of all concerned may be ever more limited, however, if the drought continues, as weather experts currently predict (Dsnews.ua, May 20).

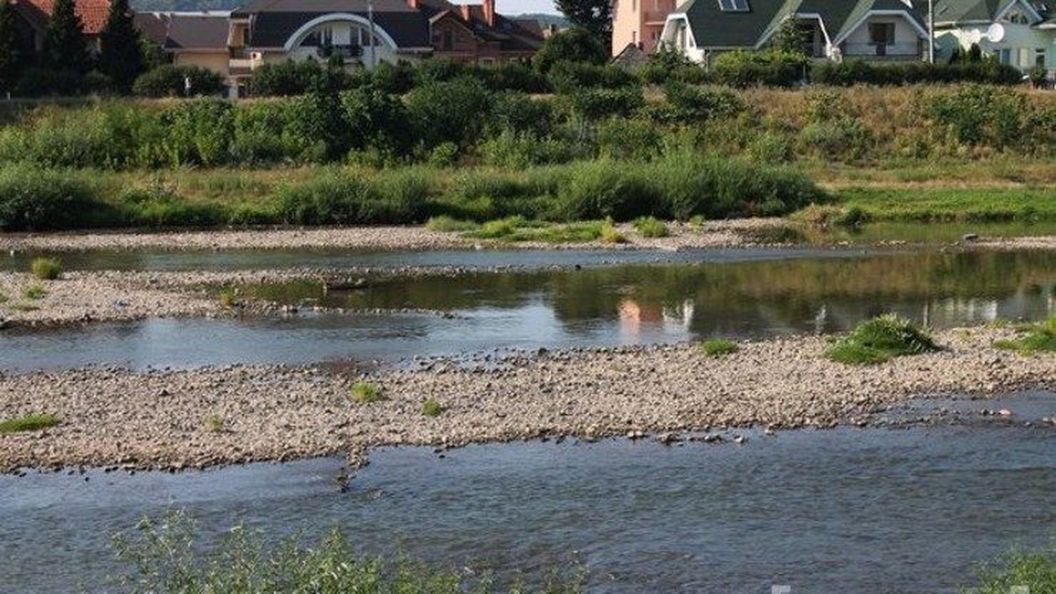

The water problems the Ukrainian authorities face are larger than they appear to recognize, Lavnikevich continues. The level of reservoirs on which Kyiv depends are lower than they have been since 1925, when the city’s population was far smaller; and experts suggest that they are likely to decline still further, putting the capital’s population at risk not only of food shortages but water shortages as well. And water levels in Ukraine’s rivers, on which the E40, a north-south waterway with Belarus and Poland, depend, are lower than they have been in decades. Indeed, in some places, they are now so low that barge traffic cannot easily pass through them; shippers have been forced either to load barges to only 65 percent of capacity or send bulk cargo via the far more expensive railways (Dsnews.ua, March 18, 25, 2019).

The Ukrainian authorities are clearly worried: At a recent meeting of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, that body’s secretary, Oleksiy Danilov, called on the government to treat the drought as a national security issue and take immediate measures to ensure “the water security of the state” this year (Rnbo.gov.ua, May 13, 2020).

Ukraine’s new infrastructure minister, Vladislav Kritkliy, promises to address that challenge by copying the policies of Western governments like France and Germany, which also rely heavily on water transport. But there are serious doubts he will be able to do so, Lavnikevich contends. First, the draft law introduced in January to address waterway restrictions has still not been passed (Rada.gov.ua, January 17). Second, even if finally adopted, the measure does not contain the financing necessary to restore the country’s internal waterways. And third, experts like Yevgeny Bachev, who heads a non-governmental organization (NGO) committed to restoring the Dnipr as a waterway, say that even if the money is found, the bill would open the way for more corruption and speculation because of its public-private partnership provisions. He told the commentator that, in his view, the new bill is no solution but rather “the worst variant of those proposed” over the last eight years (Dsnews.ua, May 20).

To the extent Bachev and Lavnikevich are right—and the evidence they present suggests they are—Ukraine faces an increasingly dire future as a result of the drought. Potentially, it may not be able to export as much as it has in previous years, lest food prices at home spike uncontrollably. It might not being able to address water shortages in areas adjoining Russian-occupied Crimea, thus making a Russian thrust there and elsewhere more likely. And finally, because of the drastic water shortages, Kyiv may no longer be in a position to participate in the construction of a trilateral north-south waterway that could be the basis for Ukraine’s eventual participation in the regional Three Seas Initiative.