Embodied Intelligence: The PRC’s Whole-of-Nation Push into Robotics

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 15

By:

Executive Summary:

- Since 2015, Beijing has pursued a whole-of-nation strategy to dominate intelligent robotics, combining vertical integration, policy coordination, rapid deployment, and local experimentation. This approach has already achieved several of its core objectives.

- Policy documents articulate an official focus on core trends and technologies like humanoid robotics, sensors, actuators, and motion control. Local governments are also diversifying applications into fields ranging from eldercare to logistics and manufacturing.

- Massive state subsidies and loans underwrite these programs, with provinces and cities engaging in a de facto “subsidy race,” each vying to foster the next national robotics champion within their jurisdiction.

- “Industrial migration” is another emerging trend, in which a growing number of electric vehicle and tech giants are entering the humanoid robotics sector due to technological and supply chain overlaps. Their scale, engineering capacity, and vertical integration allow them to lower costs, accelerate R&D, and compete aggressively in a nascent industry.

Editor’s note: This article is the first in a series analyzing the trajectory of the PRC’s robotics industry, from ecosystem formation to supply chain control to military implications. This first installment maps previously undisclosed trends, drawing on recent policy papers, investment announcements, and discussions among industry players to decode the Beijing’s approach to this increasingly important sector. Second part can be read here.

Beijing is mounting a coordinated campaign to get ahead in next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) hardware through a nationwide surge in robotics. While companies in the West like Tesla and Boston Dynamics introduced physical AI to global audiences years ago, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is now rapidly assembling an impressive array of competitors, marshalling industrial, academic, and financial resources to scale up its new national champions. The race is well underway.

At the 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference (世界人工智能大会) in Shanghai, the “National and Local Co-built Embodied Artificial Intelligence Robotics Innovation Center” (“HUMANOID”; 国家地方共建人形机器人创新中心) unveiled a new initiative to accelerate the development of humanoid robotics. It introduced fresh funding channels, training platforms, and national research hubs, all with the backing of central ministries and provincial governments (CCTV, July 28).

Across the country, similar announcements have proliferated in recent months. Since January, the central government has launched an $8.2 billion National AI Industry Investment Fund (国家级人工智能基金) to steer capital into frontier technologies, including the integration of AI into physical world. Meanwhile, local governments in Beijing, Shenzhen, and other regions have unveiled plans specifically targeting humanoid robotics (Baijiahao/Neutral Carbon Corporation Company, April 17).

First Steps: PRC’s Path to Robotics Dominance

Back in 2013, the PRC lagged behind global leaders such as Korea, Japan and Germany in robot density, even if it had become the world’s largest market for industrial robotics. Having assessed that robotics would be a key strategic industry in the future, the government began to lay the groundwork to engineer its industrial catch up.

Robotics was grouped alongside high-end computer numerical control (CNC) machine tools as one of 10 sectors highlighted in the Made in China 2025 policy, a landmark industrial strategy launched in 2015 to achieve global leadership in key emerging technologies. This policy, which anticipated many of the embodied AI ambitions now driving current PRC policy, divided robotics into three domains: industrial robots for manufacturing, service robots for human-centric environments, and special-purpose robots for hazardous or military use. (MIIT Equipment Industry Development Center, May 12, 2016). To execute the goals set in the Made in China 2025 plan, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) published the Robot Industry Development Plan (2016–2020) (机器人产业发展规划2016-2020年). This plan highlighted structural weaknesses, such as reliance on foreign core components like servo motors and control systems, and advocated for greater self-sufficiency in response (NDRC, April 27, 2016). Importantly, these calls predated the United States’s imposition of export controls during the first Trump administration.

In 2021, the 14th Five-Year Plan and its related sub-strategies further prioritized robotics, outlining specific goals in intelligent manufacturing, smart mobile robots, and cleanroom automation (using robotics within controlled environments to minimize human intervention). At the end of that year, the government released the 14th Five-Year Robotics Industry Plan (“十四五”机器人产业发展规划), which set an additional goal of becoming a global robotics leader by 2025, with an annual industry growth rate exceeding 20 percent (MIIT, December 28, 2021).

Policy momentum accelerated in 2023 with the launch of a “robotics +” action plan (“机器人+”应用行动实施方案), which promoted widespread robot adoption in manufacturing, healthcare, logistics, and education (MIIT, January 18, 2023). This was followed soon after by a set of opinions to guide innovation and development of humanoid robotics (人形机器人创新发展指导意见). These targeted humanoid systems specifically, identifying key technological bottlenecks and prioritizing breakthroughs in motion planning, cognitive AI, bionic sensing, and dexterous control systems (see Table 1) (MIIT, October 20, 2023).

Table 1: Critical Technological Bottlenecks

| Category | Focus |

| Robot “Brain” | Unified AI architecture for perception-decision control; large models; human-environment interaction. |

| Robot “Cerebellum” | Full-body coordination; terrain adaptation; motion planning; online learning and behavior modeling. |

| Robot Limbs | Biomechanics; high-speed, high-precision movement; bionic limb structures and control systems. |

| Robot Body | Structural optimization; lightweight materials; integrated energy-sensing-structure design. |

| Functional Robots | Low-cost and high-precision variants for interaction, fine motor tasks, and impact protection. |

| Sensors | Vision, auditory, tactile sensors; high-resolution and bionic sensing systems. |

| Actuators | High-power density joints; electric and hydraulic drives; compact transmission systems. |

| Controllers | Real-time motion control chips; AI decision and planning support. |

| Power Systems | High-energy batteries; power management and integration for endurance and adaptability. |

(Source: MIIT)

Mapping Priorities: What Policy Language Reveals About the PRC’s Robotics Drive

As the number of policy documents and action plans have multiply, it has become clear that the PRC is executing a full-spectrum, whole-of-nation push for global leadership in humanoid robotics. Provinces such as Zhejiang, a longstanding manufacturing powerhouse, led early by publishing PRC’s first “robotics+” policy in 2017 (Xinhua Daily Telegraph, March 17). Others quickly followed. This study has found that key provinces such as Guangdong, Jiangsu, Hebei, Anhui, and all four direct-administered municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing) have since issued their own robotics blueprints, reflecting both national alignment and local priorities (Tianjin Net, August 15, 2017; Hebei Government, June 7, 2023; Jiangsu Equipment and Industry Department, April 19, 2024; Beijing Development and Reform Commission, July 18, 2024; Guangdong Government, March 10; Anhui Department of Industry and Information Technology, May 30). Emerging tech centers like Hangzhou, where the “Six Dragons” locate including the robotics giant Unitree, and Shenzhen have also introduced robotics-specific guidance, reinforcing the PRC’s multi-nodal model of tech diffusion, from the Yellow River basin to the Yangtze Delta and the Greater Bay Area.

Figure 1: Key Robotics Hubs in the PRC

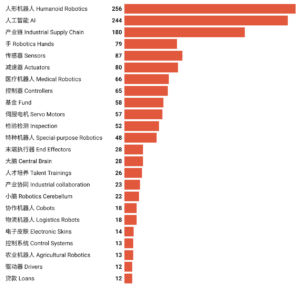

A survey of 30 national, provincial, and municipal-level policy documents based on the abovementioned areas published between 2015 and May 2025 offers a revealing window into the state’s evolving priorities. Across this dataset, “humanoid robotics” (人形机器人) and “Artificial Intelligence” (人工智能) top the list of keywords, with 256 mentions and 244 mentions, respectively (see Figure 2 below). This underscores a national pivot toward embodied intelligence systems that integrate machine capabilities and human-like functions. The emphasis reflects recent efforts from central ministries to integrate cognitive AI with physical platforms across both industrial and social domains. This explains why Beijing humanoid robotics industry revenue has grown nearly 40% in the first half of this year, accounting for about one-third of the national total (Cailian, August 8). Also, prominent across the policy documents is the phrase “industrial supply chain” (工业供应链) (180 mentions). This signals concerns over upstream resilience and import substitution, particularly in core robotics components long dominated by foreign suppliers. Frequent mention of terms like sensors, actuators, controllers, and servo motors similarly reflects ongoing efforts to localize critical hardware ecosystems and escape long-standing bottlenecks identified in the Made in China 2025 strategy.

Figure 2: Mentions of Keywords Across 30 PRC Robotics Policies, 2015–2025

Local policies reveal considerable variation from topline central directives. Specialized domains are increasingly mentioned, such as Medical Robotics (66), Special-purpose Robotics (48), and even Electronic Skins (18), and often reflect deliberate local prioritization. For example, Shanghai was among the first localities to release a white paper exclusively focused on medical robotics—a decision shaped by its advanced healthcare infrastructure and robust biomedical innovation base (Shanghai Government, October 31, 2023). The Beijing authority also issued an exclusive notice on promoting intelligent eldercare robots (养老机器人) (Beijing Bureau of Economy and Information Technology, June 12). The policy reflects efforts to integrate advanced technologies into daily life, accelerating the expansion of application scenarios and driving widespread adoption at an unprecedented scale. This indicates that technical emphasis is distributed across the country to minimize intra-provincial competition while accelerating collective progress. Local governments are increasingly seeking to carve out distinct roles within the national robotics architecture, tailoring their strategies to local industrial composition, startup ecosystems, and access to talent and capital.

The PRC’s use of state-backed financing to drive the industry is apparent in the frequent mentions of “funds” (58) and “loans” (12) across these policy documents. Government guidance funds help robotics startups and designated strategic companies scale key technologies, while loans offer support for R&D commercialization. Jiangsu has offered up to RMB 30 million ($4.2 million) in subsidies for robotics manufacturing innovation centers (Jiangsu Equipment and Industry Department, April 19, 2024). Guangdong prioritizes funding for innovation platforms, offering RMB 50 million ($7 million) in fiscal support for robotics centers and up to RMB 100 million ($14 million) for approved special projects (Shenzhen Government, April 28, 2023; South Plus, April 1). Meanwhile, Zhejiang integrates robotics into consumption-boosting policies, offering 15 percent subsidies—up to RMB 2,000 ($280) per unit—for smart home robots through its appliance trade-in program (Baidu/JRJ.com, May 20). At the city level, Suzhou provides up to RMB 200 million ($28 million) for robotics research institutions, particularly those aiming to become national labs (Suzhou Legal Bureau, June 9). These examples underscores the PRC’s sustained reliance on subsidies and credit instruments to steer and accelerate priority tech sectors through early-stage uncertainty and financial volatility. As a result, provinces and cities are engaged in a de facto “subsidy race,” each vying to foster the next national robotics champion within their jurisdiction.

From Patent Race to Factory Floor: PRC’s Two-Track Robotics Surge

The PRC’s robotics campaign currently is advancing along two tightly coordinated fronts: scaling physical deployment and securing dominance in future innovation domains. In 2023, the country made over 276,000 industrial robot installations, nearly six times that of Japan and far surpassing the United States, South Korea, and Germany, and indicating the fruition of several years of policy support (see Figure 3 below). The current installation figures indicate that they country successfully met annual production targets set by the NDRC in 2016 for 2020 (NDRC, April 27, 2016).

Figure 3: Installations of Industrial Robots by Country 2023

(Source: International Federation of Robotics)

In terms of intellectual property, however, Chinese firms continued to lag long-established Japanese and Korean players (see Figure 4 below). While 2023 data shows PRC firm UBTECH (优必选) leading in global patent filings—with growing contributions from institutions like Tsinghua University, Beijing University of Technology, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences—long-established Japanese and Korean players still dominated the intellectual property space. though the gap is shrinking. As of 2025, the PRC accounts for nearly 60 percent of global AI-driven robotics patent filings, signaling not only dominance in output, but also growing influence over the future trajectory of embodied AI (PatentPC, July 31).

A similar trend emerges in robotics-related research. Between 2015 and 2022, the PRC recorded a 545 percent increase in first-author robotics publications, and a 256 percent rise in the number of institutions conducting robotics research. The PRC overtook the United States in total publication volume in 2022 (The China Academy, October 24, 2023). The result is a rapidly expanding ecosystem in which academic, industrial, and state-driven innovation are increasingly synchronized.

Here it is necessary to emphasize the distinction between industrial and humanoid robots. While the PRC is already delivering measurable outcomes in the former, in the latter it remains in its early incubation stage, with production only recently beginning. This production is driven largely by university labs, intellectual property competitions, and long-cycle capital. However, as policy attention and investment increasingly converge on embodied AI, this gap also is likely to narrow. According to the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology , the PRC’s humanoid robotics industry reached a market size of nearly RMB 2.8 billion ($380 million) in 2024 and is projected to grow into a RMB 100 billion market by 2030 (CCTV, September 12, 2024).

Figure 4: Number of Valid Humanoid Robotics Patents by Organization (2023)

(Source: Created by the author based on data from CNIPA and WIPO)

Figure 5: Number of Cumulative Humanoid Robotics Patent Applications by Country (2015–2022)

(Source: Created by the author based on data from CNIPA and WIPO)

EV and Tech Sectors Fuel Humanoid Robotics

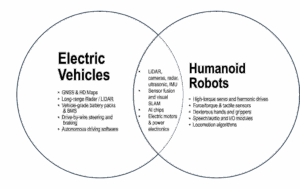

“Industrial migration” is an emerging trend shaping the PRC’s robotics industry, whereby the country is increasingly leveraging its mature electric vehicle (EV) ecosystem to support its nascent robotics sector. Leading EV companies like XPeng (小鹏汽车), BYD (比亚迪), GAC (广州汽车集团), and Li Auto (理想汽车) are repurposing EV technologies for robotics, capitalizing on shared system architectures. Both EVs and humanoid robots operate on a “perception–decision–execution” loop, using sensors to perceive their environment, processing information in real time, and autonomously taking actions in response (Sina Finance, May 23).

On the perception side, technologies developed for autonomous driving—such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), cameras, ultrasonic sensors, radar, and inertial measurement units (IMUs)—are now being widely adopted in humanoid robot navigation and vision systems (Nvidia, April 15, 2019). These sensors feed into sensor fusion algorithms and SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping) systems, which are standard in self-driving vehicles and now widely adopted in humanoid robot navigation and vision. The same AI processors originally developed for automotive autonomy—including neural processing units (NPUs), graphics processing units (GPUs), and CPU/system-on-chip (SoC) architectures—also are being repurposed in humanoid robots to support environment modeling, motion planning, and real-time decision-making (South Plus, April 11).

The execution layer shows similar alignment. EVs rely on high-torque electric motors, precision servo drives, and battery management systems (BMS), all of which are essential for powering a robot’s limbs, joints, and core systems. Thermal and energy management systems originally designed for EVs platforms, including advanced cooling solutions, can also be applied to robots, which face comparable challenges in heat dissipation and endurance. Even vehicle chassis control systems, like drive-by-wire and braking logic, conceptually align with robotic joint control and limb coordination (Auto Business Review, June 3).

As a result, Chinese EV makers are not entering humanoid robotics space as complete outsiders but as well-positioned incumbents, accelerating the commercialization of humanoid platforms with existing R&D, talent, and infrastructure.

Figure 6: Venn Diagram of Technologies Shared by Electric Vehicles and Humanoid Robots

(Source: Created by the author)

As this ecosystem evolves, major players are emerging as both investors and system architects. EV manufacturers such as XPeng, BYD, GAC, Li Auto, Changan (长安汽车), and Geely (吉利) are building in-house robotics teams, and also collaborating with or investing in top robotics companies like UBTECH, Unitree (宇树科技) and Leju (乐聚机器人). These partnerships allow carmakers to directly apply their competences to developing humanoid robot performance. For example, XPeng’s “Iron” robot uses the same autonomous driving system and in-cabin AI from its EVs to enable 720° visual perception and voice interaction. Meanwhile, BYD uses its vertically integrated supply chain to self-produce 80 percent of core components like harmonic reducers and torque sensors at scale, achieving a 30–40 percent cost reduction (Weibo/Zhineng, December 29, 2024; QQ/Zhixin Lele, April 17). The company plans to deploy 2,000 robotics at its production lines this year.

EV firms also bring manufacturing muscles, deploying their factories—that are already optimized for modular, high-precision assembly—to scale robotics production. NIO (蔚来汽车) and Geely have partnered with Unitree and other leading robotics companies to transform their factories into testbeds for robotics startups, providing real-world environments to fine-tune robotic navigation, manipulation, and coordination (Late Post, June 11; Xinjing News, July 29). GAC’s GoMate robot integrates a force control system adapted from its EV drive platform. By transplanting torque control algorithms, it reportedly achieved a 50 percent improvement in single-leg balance response time and accelerated force control system development by nine months ahead of the industry average (Jiemian, December 25, 2024).

On the tech front, Meituan’s founder Wang Xing (王兴) has emerged as the PRC’s most prominent investor in embodied AI, supporting over 30 robotics-related startups and building a full-stack “robot army” spanning hardware, AI brains, and real-world scenarios (TMT Post, July 25). ByteDance has exceeded 1,000 units in robot production, deploying them across logistics and retail sectors (Late Post, July 2). Tencent and Alibaba have funded key players like AgiBot (智元机器人) and Galaxea AI (星海图), focusing on modular perception, bionic cognition, and general-purpose AI brains (Cailianshe, July 21). Xiaomi combines to integrate end-to-end hardware R&D with ecosystem investment across actuators, chips, and algorithms to reinforce its CyberOne platform (Haokan Video, March 8). Finally, U.S.-blacklisted battery giant CATL (宁德时代) has also entered robotics realm, leading the largest single funding round in the country’s embodied intelligence sector through its investment in Galbot (银河通用), a rising general-purpose robotics company (Xinhua, June 23). In the first half of 2025, total financing in the humanoid robotics sector has already reached a record high, exceeding 10 billion RMB ($1.4 billion) (CCTV, July 27).

Figure 7: The Tech Sector Backgrounds of Leading Robotics Firms

(Source: Created by the author)

Huawei also is emerging as a key player. In 2024, it launched an Embodied AI Industry Innovation Center (全球具身智能产业创新中心) in Shenzhen, partnering with the municipal government alongside 16 companies, including Leju Robotics and Hechuan Technology (禾川人形机器人) (The Paper, May 16). Huawei also signed a strategic agreement with UBTECH to co-develop humanoid technologies. In collaboration with China Mobile and Leju, Huawei unveiled the industry’s first 5G-A humanoid robot, addressing complex challenges like multi-agent coordination and real-time decision-making (Sina Finance, June 20). This wave reflects more than enthusiasm—it marks a structural shift, with EV and tech giants treating humanoid robotics not as speculative ventures but as strategic extensions of their core AI and smart hardware ambitions.

Conclusion

The rise of the PRC’s robotics industry represents a tightly coordinated, whole-of-nation campaign driven by national strategy, regional policy alignment, and deep industrial integration. At its core is a convergence of capabilities—spanning electric vehicles, AI platforms, sensors, and advanced manufacturing—that enables rapid transition from concept to commercialization. This emerging model of vertical integration and cross-sector collaboration is reshaping global supply chains and production paradigms. If successful, it may redefine global standards for intelligent machines. Policymakers and industry leaders alike should closely examine how the PRC is systematically aligning state planning with industrial execution to accelerate technological dominance and secure long-term strategic advantage.