Energy and AI Coordination in the ‘Eastern Data Western Computing’ Plan

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 4

By:

Executive Summary:

- The “Eastern Data Western Computing” plan is a multiagency strategy that coordinates cloud computing data centers and energy infrastructure across the People’s Republic of China. These are increasingly relevant with the rise of artificial intelligence.

- This cloud infrastructure buildout likely will not rival that of the United States, but its coordination with renewable energy capacity means that the country’s digital infrastructure will be sustainable, based on a resilient energy system, and foster economic development opportunities in underinvested regions.

- Early plans for building data centers in Western China were backed by Li Zhanshu, later Xi Jinping’s chief of staff, and key support from other influential officials likely were key to establishing Guizhou as a hub in the national system.

- Many of the hubs’ locations are remote and have climates and geographic features that make them suitable for hosting data centers that can perform energy-intensive functions that do not necessarily require “real-time” computation and ultra-low latency.

The training and deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) models is predicated on an enormous energy supply. This has ushered in a new rush for resource security—both for power generation and water use, as the data centers on which these technologies rely consume large amounts of water to keep them from overheating (Semianalysis, February 13). Currently, the United States leads the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in number of data centers by a wide margin (Statista, October 11, 2024). However, given the energy needs of cloud computing and AI, which continue to expand, there is a growing imperative for coordinating energy and cloud investment.

In the PRC, the “Eastern Data Western Computing” (东数西算) plan is a multiagency national initiative to do just that. While the United States lacks a national strategy to coordinate cloud computing and energy use, instead relying on disconnected regional initiatives and private-sector led investment, the PRC’s plan serves as an illustration of the potential benefits such coordination offers at national and local scales (NDRC, February 22, 2022; NCSTI, accessed February 26).

Political Backing Sees Guizhou Lead National Plan

The “Eastern Data Western Computing” plan has its origins in the efforts of Guizhou province to establish itself as an inland hub for cloud computing. The Gui’an New Area (贵安新区) was initially proposed in 2011 by Li Zhanshu (栗战书), then a key provincial leader and later a politburo standing committee member and President Xi Jinping’s chief of staff. It was finally approved by the State Council in early 2014 (Gui’an New Area, February 5; Journal of Contemporary Asia, February 15, 2024). Around the same time, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) released a national plan to optimize data center distribution, laying the groundwork for provincial initiatives (MIIT, January 14, 2013). Guizhou’s rise as a cloud computing hub was further reinforced by key personnel transfers. Chen Gang (陈刚), who had previously helped oversee Beijing’s Zhongguancun high-tech district, was appointed Party Secretary of the provincial capital Guiyang, where he implemented policies to support the region’s nascent cloud computing sector, while from 2012–2017, Chen Min’er (陈敏尔), a close Xi associate from Zhejiang Province, served first as Guizhou’s governor and later as its party secretary (People’s Daily Online, March 6, 2014; Guiyang Government, May 31, 2014). This political backing enabled the province to position itself as a national leader in cloud computing, capitalizing on its cool climate and abundant hydropower resources. By 2014, Guizhou formally launched its big data initiative to the tech industry with the “Guizhou-Beijing Big Data Industrial Development Promotional Conference,” held in Zhongguancun, where Chen Gang served (Journal of Contemporary Asia, February 14, 2024). Since then, Gui’an New Area has attracted data centers from tech giants such as Tencent, Huawei, Apple’s first data center in the PRC, China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom.

Efforts to establish a national digital infrastructure framework accelerated in 2018. The central economic work study group introduced the concept of “new basic infrastructure” (新基建), followed by the National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC) 2020 Guidance on Accelerating the Construction of a National Integrated Big Data Center Collaborative Innovation System (关于加快构建全国一体化大数据中心协同创新体系的指导意见) (Oriental Outlook Weekly, April 26, 2020; NDRC, December 28, 2020). These initiatives build on longstanding regional development strategies, such as the Great Western Development (西部大开发) campaign launched in 1999 to address economic disparities between western provinces and coastal cities (China Brief, March 28, 2002). In recent years, the PRC has intensified data center construction to enhance computing capacity and compete with the United States. This has culminated in the 2021 Implementation Plan for the Computing Power Hub of the National Integrated Big Data Center Collaborative Innovation System (全国一体化大数据中心协同创新体系算力枢纽实施方案). Issued by four national agencies—NDRC, the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission, MIIT, and the National Energy Administration—this plan formally established the “East Data, West Computing” strategy, redistributing digital infrastructure as a strategic economic and geopolitical move (NDRC, May 24, 2021).

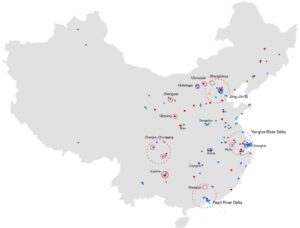

Figure 1: Existing Data Centers and Planned Clusters Under the ‘Eastern Data Western Computing’ Plan

(Source: Author, based on information scraped from official sources)

The “Eastern Data Western Computing” plan aims to optimize the PRC’s computing network by incentivizing data center construction in energy-rich western regions, thus improving the resource efficiency of data centers by lowering power usage effectiveness ratios and leveraging cloud computing to stimulate economic growth in less developed provinces. [1] The plan promotes inland data center development alongside investments in high-speed fiber optic transmission, allowing remote regions to better integrate into the national computing network (Huawei, March 2022). It designates ten “data center clusters” (数据中心集群) within eight “national hub nodes” (国家枢纽节点) encompassing both western provinces and key metropolitan areas, including Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Ningxia, Chengdu-Chongqing, Zhangjiakou, Wuhu, and Shaoguan (See Figure 1) (NDRC, May 24, 2021). By August 2024, the government had invested RMB 44 billion ($6 billion) in the initiative, leveraging over RMB 200 billion ($27 billion) in total investment, with publicly disclosed projects suggesting an estimated RMB 240 billion ($33 billion) allocated to “Eastern Data Western Computing” clusters by the end of 2024 (Xinhua, 2024).

The idea of moving data centers to inland regions initially seemed counterintuitive and at odds with market demand. The PRC’s data centers largely have been concentrated in metropolitan hubs along the eastern seaboard to minimize latency for real-time applications. However, remote data centers are suited for energy-intensive data functions that do not necessarily require “real-time” computation and ultra-low latency. According to the “Eastern Data Western Computing” plan, nodes such as Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Ningxia that are “rich in renewable energy and have suitable climates” (可再生能源丰富、气候适宜) will become part of a “national base for non-real-time computing power” (面向全国的非实时性算力保障基地), performing functions such as “background processing, offline analysis, and storage backup” (后台加工、离线分析、存储备份) (NDRC, May 24, 2021).

Plans Preempt AI Demand, Energy Supply Concerns

More recently, training AI models has also become an imperative for cloud computing companies, something for which remote data centers are also suited. Many PRC firms have built their own AI data centers featuring custom-made chips, such as Baidu AI Cloud’s Kunlun AI chip-powered data centers, Alibaba Cloud’s HPC AI clusters, and Huawei’s Ascend-powered AI computing centers. Others are finding other ways of getting around export bans on advanced chips through both licit and illicit means (China Brief, December 6, 2024). Some have been successful. One private data center executive told me that his firm had established a subsidiary in Qinyang, one of the plan’s designated hubs, which was likely being used for AI model training with Nvidia chips—hardware restricted under U.S. export controls (Author interview in Beijing, 2024).

Ideas for optimizing data center location based on climate and energy concerns were circulating among researchers and officials under ministries like MIIT back in 2013 (MIIT, January 14, 2013). Gui’an New Area became the first in a series of inland data center hubs whose development was accompanied by investment in renewable energy and other utility infrastructures like smart grids, but others have followed suit.

Gui’an New Area’s Energy Reform Pilot

The growth of data centers in Guizhou exemplifies how digital infrastructure development requires coordination between local and national governments, state-backed energy firms, and private technology companies. For local officials, cloud computing was not just a technological investment but a development strategy for one of the country’s poorest regions. To attract capital, the provincial government implemented tax incentives, including five-year exemptions for data centers and a reduced 15 percent corporate tax rate, while also subsidizing renewable energy integration. Recognizing the immense energy demands of large-scale data operations.

Gui’an New Area was designated an energy reform pilot zone, where the local administrative committee partnered with Guizhou Power Grid (贵州电网), a subsidiary of China Southern Power Grid (中国南方电网), to create a deregulated energy market and provide a springboard for regional energy company expansion. This initiative drew investments from power producers such as Huaneng (华能) and Guodian (国电), spurring the construction of new renewable power stations. By 2023, data centers consumed 60 percent of Gui’an New Area’s electricity, with approximately 70 percent sourced from renewables, illustrating the region’s prominent position in the evolving national cloud infrastructure (NDRC, November 26, 2015).

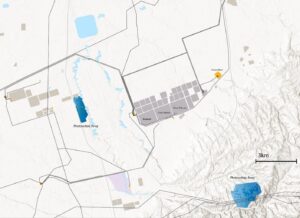

Figure 2: Zhangjiakou Energy Infrastructures

(Source: Author, based on data collected from data companies and open infrastructure map, 2024)

Zhangjiakou’s Renewable Energy Demonstration Zone

The geographic endowments of Zhangjiakou, a historic military garrison for Beijing (and one that still hosts the 82nd Group Army), make it ideal for wind and solar energy production. In July 2015, the State Council approved the establishment of the Zhangjiakou Renewable Energy Demonstration Zone, the country’s first and only national-level renewable energy demonstration zone (Irena, November 2019). A wind energy industrial ecosystem has emerged in the area, including the Hengzhi Science Park, which attracts turbine manufacturers and energy storage companies. The PRC’s state-owned energy giants, including China Datang (中国大唐), China Three Gorges (中国三峡集团), and Huaneng, played a key role in developing large-scale renewable projects such as the Zhangbei Wind Farm and Zhangbei Solar PV Park. By 2020, Zhangbei County had built one of the country’s most extensive renewable energy clusters, with 15 GW of installed wind power capacity and 6.3 GW of solar capacity accounting for an estimated 75 percent of the county’s total energy production (WWF & Shenzhen Institute, 2020).

Officials raised concerns about Zhangjiakou’s limited water resources. Data centers require significant amounts of water for cooling in an arid region, and at the time they were consuming nearly 50 percent of the city’s electricity, and projections indicated that demand would double to 14 TWh annually (Irena, November 2019). Undeterred, authorities have built a new data center cluster in Zhangjiakou near the Guanting Reservoir, just across the border with Beijing (see Figure 2). Zhangjiakou’s proximity to Beijing and its renewable energy potential have made it an attractive location for cloud computing firms. In 2016, Alibaba established a major data center in Zhangbei County, one of the northernmost parts of the city’s sprawling jurisdiction. GDS (万国数据), a leading third-party data center operator, followed suit with a facility near Alibaba’s campus.

Zhangjiakou’s role in digital infrastructure was further solidified in 2021, when the city was designated a key data center cluster serving the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (“Jing-Jin-Ji”) region under the “Eastern Data Western Computing” plan (China Brief, March 1, 2024; Zhangjiakou News, accessed February 27). This inclusion reinforced the government’s commitment to balancing Beijing’s data demands with Zhangjiakou’s renewable energy capacity. The city’s importance was again elevated by its selection as a host location for the 2022 Winter Olympics. This spurred a wave of infrastructure investment, improving connectivity and facilities essential for data center operations. That same year, Zhangjiakou deepened its partnership with private-sector cloud operators with global connections. For example, Chindata, a data center company backed by U.S. private equity firm Bain Capital, recently signed a 10-year strategic cooperation agreement with Zhangjiakou’s state-owned Construction and Investment Group (Chindata, August 31, 2023). It has since established four facilities across multiple counties in Zhangjiakou, aligning with national sustainability priorities while expanding its footprint. Chindata also has a new, massive data center in nearby Datong, Shanxi Province. More recently, Huailai County—Zhangjiakou’s closest county to Beijing—has emerged as a new focal point for data center investment, attracting major players such as Tencent, China Mobile, China Unicom, and China Telecom.

According to the 2024 China Comprehensive Compute Index Report (中国综合算力指数报告), published by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (中国信息通信研究院), Zhangjiakou’s Huailai County is a “shining ‘star’” (闪亮的“星), leading the country in terms of compute (Hebei Daily Client, February 25).

Figure 3: Hohhot Energy Infrastructure

Hohhot

China Telecom began work in 2011 on a data center just south of the Inner Mongolian capital of Hohhot (Hohhot Government, July 2, 2024). In 2016, Inner Mongolia unveiled a big data strategy for the autonomous region aiming to replicate Guizhou’s efforts (Inner Mongolia Daily, October 26, 2016). As with other data center hubs, the region has ample renewable energy potential in solar and wind as well as favorable cool and dry climate. The area is being branded as “China Cloud Valley” (中国云谷) and is part of a broader plan for a new area that aims to draw digital industries beyond data centers. To this end, China Mobile has opened a massive facility near China Telecom, and data centers are planned for national banks (Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, and China Construction Bank), as well as facilities for UCloud and Huawei (Xinhua, October 20, 2023, January 24; UCloud, accessed February 26).

Conclusion

So far, the “Eastern Data Western Computing” plan’s outcomes have been mixed. Hub areas that were already home to some cloud operations (such as Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, and Zhangjiakou) have continued to attract steady investment. More remote areas like those in Gansu and Ningxia are still relatively under-established and may struggle to attract substantial investment beyond state-owned telecoms. Limitations on remote data centers include the costs of building additional fiber optic cable to speed transmission and limited local human capital of skilled engineers and technicians to man data centers. However, the scale of investment from national policies combined with subsidies and tax breaks from local governments, will likely spur at least some investment even in these remote hubs.

For now, the country’s overall computing power, measured both in the number of data centers, as well as the overall market share of cloud companies, lags behind that of the United States. Even if the full planned investment of the “Eastern Data Western Computing” data centers is completed, the PRC will likely remain behind. However, the PRC’s effort to coordinate renewable energy infrastructure and data center buildout is noteworthy. Its multiple benefits include sustaining cloud computing power, strengthening energy system resilience, and fostering economic development opportunities in underinvested regions. For the United States to continue to lead in computing, the PRC approach contains useful lessons.