Evidence of French Intelligence Agency Rejected in Appeal of Former Guantanamo Inmates

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 7 Issue: 6

By:

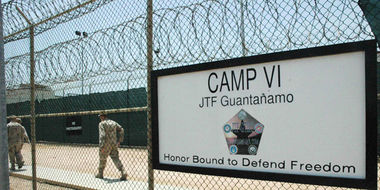

They were already free. Now, they are innocent. On February 24, the Appeals Court in Paris overturned the conviction of five French Muslims, all former Guantanamo detainees repatriated in 2004 and 2005, on the charge of “criminal conspiracy in relation to a terrorist enterprise." Brahim Yadel, Mourad Benchellali, Nizar Sassi, Khaled ben Moustapha, and Redouane Khalid were convicted in December 2007 of attending al-Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan in 2001. Their trial and the overturn of their conviction illustrates that the continued existence of Guantanamo is not simply an American problem, but one that could have far-reaching ramifications for how France prosecutes terrorism cases.

All five men acknowledged traveling to Afghanistan and enrolling in al-Qaeda-sponsored training camps. However, two of the men, Mourad Benchellali and Nizar Sassi, testified that they were tricked into joining the camp. They also added, along with Brahim Yadel, that they did not support Osama Bin Laden’s ideology. The circumstances that brought Redouane Khaled’s and Khaled Ben Moustapha to Afghanistan are not entirely clear. Local security forces detained four of them (Yadel, Benchellali, Sassi, and Moustapha) as they were trying to cross from Afghanistan into Pakistan to make their way back to France in the aftermath of 9/11. Nevertheless, joining a training camp may fall under the statute of “criminal conspiracy in relation with a terrorist enterprise.”

The fact that the five men were imprisoned at Guantanamo without charges weighed heavily on the outcome of the 2007 circuit court trial. The prosecutor argued at the time that “None of these men should have been detained there [Guantanamo], in complete disregard with international norms; and none of them should have been subjected to what they have been subjected to” (AFP, December 11, 2007). Indeed, the prosecutor asked the tribunal to sentence the men because they were guilty of joining the camp, but asked for light sentences so that the men “would not return to prison” after time served in preventive detention. On December 12, 2007, the tribunal sided with the prosecution’s request for light sentences and condemned the five men to a year in prison. Three of the accused received an additional four years of suspended jail-time. According to the prosecutor, “I would not have requested the same imprisonment terms if they had not been in Guantanamo,” thus hinting that she would have requested longer sentences had the men not been sent to Guantanamo in the first place. It is actually unclear that this would have been the case. As a declassified note from the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST – France’s domestic intelligence agency) explained: “In case of repatriation to France, it may not be feasible to imprison and try them, because they did not commit any particular offense in France” (Rue 89, December 12, 2007).

In a lengthy sixty-page decision, the Appeals Court reversed the conviction, arguing that the conditions under which the DST was allowed to interrogate the five French citizens in Guantanamo violated the defenders’ legal rights. The DST went three times to Guantanamo to interview the French prisoners; in January 2002, March 2002, and January 2004. For the court, the “proofs” the prosecution presented had been tricked out of the defenders, who “were led to believe that their [incriminating] statements were necessary to obtain their repatriation in France and were not in a position to realize that they would be used against them” (L’Express, February 24). In consequence, the court ruled the statements obtained by the DST during their inquiry were inadmissible and concluded that, absent any other material evidence, there were no “elements to establish the culpability” of the accused (L’Express, February 24).

The decision highlighted the ambiguous role of the DST in counter-terrorism cases. The DST is a hybrid institution, acting both as an intelligence service designed to gather information in order to thwart a terrorist threat and as a police branch supporting the prosecution of terrorism cases. In each case, the DST operates under different sets of rules; according to the Appeals Court, the DST “cannot confuse the two procedures” without violating the rules of criminal procedure and the principles of international law (Le Monde, February 25).

After the prosecutor’s office opened its initial inquiry in February 2002, all subsequent DST interrogations of the suspects should have respected the rules of criminal procedure. According to the Appeals court, such was never the case, as the DST gathered evidence against the detainees under the cover of gathering intelligence (subject to a different set of procedures). According to the court, the DST debriefings cannot be considered “a case of intelligence collection in order to thwart a terrorist threat,” concluding the DST could not act as both an intelligence agency and a judicial police force (Le Monde, February 25; Le Figaro, February 24).

In addition, the Court found that the DST’s ambiguous role in the case was concealed from the justice system. In the initial trial, which began in the summer of 2006, the notes from the DST’s secret missions served as the basis for the accusation (Rue 89, December 12, 2007). However, because they were classified, the documents were never passed on to the defense. The discovery of the secret notes during the 2006 trial led to an adjournment, during which the judge, Jean-Claude Kross, requested an additional inquiry and asked for the declassification of the DST’s debriefings. [1] At that point, Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ representatives and DST officials conspicuously refused to provide details of their missions (Le Monde, February 20, 2007). It was only after an anonymous source tipped the tribunal as to the identity of the two DST agents who carried out the missions in Guantanamo that the DST agreed to release the memos.

The defense lawyers were elated by the Appeals Court judgment and saluted its historic decision. It is the first time that a terrorism procedure was thrown out because of the DST’s dual role. Said William Boudon, one of the attorneys; “This is an historical decision that defines the red line a democracy cannot cross” (Le Monde, February 25). The prosecutor’s office immediately appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court. A source in that office bitterly remarked; “this is tantamount to validating disloyalty” (Le Monde, February 25).

Notes:

1. “Peine de principe: Mais quel principe,” chroniquedeguantanamo.blogspot.com, December 20, 2007. https://chroniquedeguantanamo.blogspot.com/2007/12/peines-de-principe-mais-quel-principe.html.