Scandinavian Trials Demonstrate Difficulty of Obtaining Terrorist Financing Convictions

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 7 Issue: 5

By:

As the international community gears up for reconstruction efforts in Gaza, a number of European Union members are grappling with the question of how to deal with the alleged funding of Hamas through a number of charities. A Swedish court’s February 17 acquittal of Khalid al-Yousef on charges of terrorist financing and violating EU sanctions is the latest in a series of actions attempting to target al-Aqsa Foundation, believed by many security services to be a conduit for funds from Europe to Hamas. Al-Yousef’s acquittal echoes a 2008 decision in Denmark in which two men charged with terrorist financing through al-Aqsa were narrowly acquitted by a divided court.

In largely similar cases, EU members have taken a wide variety of legal and administrative actions against organizations carrying the al-Aqsa name. In Sweden and Denmark, lengthy criminal investigations followed by criminal prosecutions have both ended in acquittals. This is in part because of the high evidentiary standards applied by the courts, but mainly because much of the evidence provided by Israel was discarded. The reliance on evidence from Israel and lower evidentiary thresholds were important factors in several German and Dutch court decisions to uphold administrative bans on al-Aqsa organizations in those countries. By contrast, the Belgian government has not attempted to shutter the organization’s offices in Verviers and Brussels.

Court cases over the legality of bans on al-Aqsa and the organization’s inclusion on the EU terror list have highlighted a number of the security challenges and humanitarian tradeoffs inherent in prosecuting suspected cases of terrorist financing. The Swedish and Danish trials showcase the most recent developments.

Al-Aqsa in Sweden

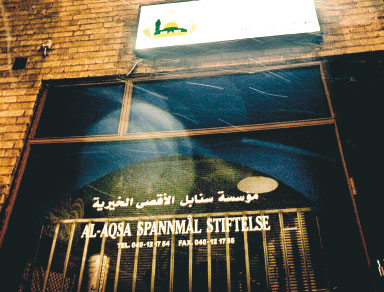

Khalid al-Yousef, head of al-Aqsa Spannmål Stiftelse (al-Aqsa Grain Foundation) in Malmö, Sweden, was brought to court on charges of terrorist financing and breaking EU sanctions prohibiting support to Hamas. Al-Yousef agreed that he had collected money and transferred it to charities in Palestine including the Jenin Charity Committee, the Islamic Society, WYMA, and Human Appeal, but he denied that the recipient organizations were part of Hamas or that the purpose was to finance terrorism. [1]

The crux of the prosecution’s argument was that money sent from al-Aqsa Spannmål Stiftelse to charities in Gaza may have been used to support the families of deceased terrorists, thus encouraging terrorism. The court dismissed the charge, however, because Swedish law does not explicitly prohibit such support. On the charge of breaking EU sanctions, the court found that the total evidence put forth “to some extent indicates that one or more of the organizations to which Khalid al-Yousef has sent money may be a part of Hamas, and the transaction thus prohibited. The evidence presented, however, is not sufficient for a conviction.”[2]

The court’s verdict followed a tough evaluation of the evidence presented. The court said that because Israel and Hamas are engaged in a “war-like situation,” the Israeli view of Hamas as a terrorist organization and the outlawing of the charities in question “should be regarded as entirely irrelevant.” [3] The court also rejected documents seized by Israeli authorities in Hebron in June 2002 that allegedly show that Hamas’ social, political, and military activities are all related. Because the documents’ authenticity could not be verified, they had “very little or no value” as evidence. Lastly, the court said that evidence from two trials by an Israeli court in Samaria “cannot be given any decisive importance” because of the “war-like situation” in Israel and Palestine, as the trials were conducted on occupied territory and the original documents were not presented. [4]

Citing various concerns, the Swedish court largely discarded as evidence an FBI wiretap of a 1993 meeting of Hamas operatives in Philadelphia, a statement from the PLO, and a letter from the late Shaykh Ahmad Yassin (the spiritual leader of Hamas) that had been used in a German trial. The evidence the court found to be most credible was wiretaps indicating that al-Aqsa supported the families of martyrs and Hamas activists, and that money sent to Human Appeal may have been forwarded to other charities.

In an interview with Sydsvenska Dagbladet, Judge Rolf Håkansson reiterated the court’s view that the evidence presented had been inadequate: “Can you base a conviction on newspaper articles, TV clips, and excerpts from books?” (Sydsvenska Dagbladet, February 18). Prosecutor Agneta Qvarnström stated that although there was perhaps no single piece of evidence sufficient on its own for a conviction, she believed that the total picture presented by the circumstantial evidence was quite convincing.

Especially interesting in terms of the alleged sanctions law violation is the court’s argument that while a wiretap suggests that al-Aqsa Spannmål Stiftelse “supports the families of martyrs… this does not show that there is an economic connection” to Hamas. It appears that the court has not considered the fungibility aspect whereby support given to the families of “martyrs” or Hamas members may free up Hamas’ funds for other purposes. This argument assumes that Hamas would fund the families of “martyrs” if charities were not doing so. Many terrorist groups have consistently supported the families of killed or incarcerated members. An interesting state example is Saddam Hussein’s history of funding the families of Palestinian “martyrs” and the significant support he won in Palestine as a result (BBC, March 13, 2003). It appears likely that the prosecution will appeal the case (Sydsvenska Dagbladet, February 18).

Al-Aqsa in Denmark

The case against al-Aqsa in Copenhagen, settled by Denmark’s highest court in February 2008, mirrors the Swedish case in many aspects. Local al-Aqsa directors Rachid Mohamad Issa and Ahmad Mohamad Suleiman stood accused of financing Hamas through three of the same charities as the Malmö-based organization. [5] Like al-Yousef in Sweden, Issa and Suleiman said they had collected and transferred money to the charities, but denied that the purpose was to support Hamas or the families of suicide bombers. Much of the evidence in the trial was identical to the Swedish case, and the issue of how to evaluate evidence provided by Israel proved central to the outcome of both trials. The Danish court also largely dismissed the charge that funding the families of “martyrs” should be viewed as terrorist financing (Politiken, February 6, 2008).

The Danish court split 3-3 on six of the eleven charges in the case, illustrating both the complexity of terrorist financing cases and differing views on how to interpret newly adopted laws. For example, Issa and Suleiman faced charges of supporting the Islamic Charitable Society (ICS), which the Danish prosecutor argued was a part of Hamas. The court split evenly, with three judges in favor of a conviction and three against. Those judges in favor of a conviction found the 1993 FBI wiretap relevant, emphasizing that ICS leaders had been members of Hamas and that ICS had given more support to the families of dead or incarcerated members of Hamas than to other needy individuals.

Those judges against a conviction found no decisive evidence that ICS leaders were working in conjunction with or at the direction of Hamas, regardless of whether some ICS leaders were also members of Hamas. They also disregarded the FBI wiretap as too old.

On the question of whether financing the families of “martyrs” or incarcerated Hamas members facilitates terrorism, the judges agreed that in order to prove such a charge, the prosecutor needed to show that such support in isolation facilitates the criminal activity. None of the judges found that connection have been proven. In sum, although the court was divided 3-3 on six counts, Issa and Suleiman were acquitted of all charges. [6]

Al-Aqsa in Europe

Al-Aqsa got its start in Europe in 1997, when Mahmoud Amr registered al-Aqsa e.V. (e.V. = Eingetragener Verein – a registered club in Germany) in Aachen, Germany, Al-Aqsa Humanitaire in Verviers, Belgium and Stichting al-Aqsa in Heerlen, the Netherlands. Similar to the proximity between the Malmo and Copenhagen offices, the al-Aqsa offices in Aachen, Heerlen, and Vervier were all less than 30 miles from one another. Amr, whom the United States has accused of being “an active figure in Hamas,” was an original signatory to the charters of all three organizations. [7]

Germany

In May 2002, Israeli officials pressed Germany to shut down the organization in Aachen, but Germany resisted, insisting that monitoring the group would yield more actionable information than shutting it down. That summer, however, German authorities reversed course, issuing an administrative order banning al-Aqsa e.V. in Aachen, in part to send a clear message that Germany would not serve as a safe haven for radical Islamists (Frankfurter Allgemeine, August 5, 2008).

Al-Aqsa e.V. took the German decision to court and won permission in July 2003 to resume operations under government supervision. A higher German court reinstated the ban in December 2004, ruling that the government had been correct in ordering the organization’s dismantlement. In its press release, the court added that “While it is impossible to prove that the funds transferred to the welfare organizations were used (in part) indirectly by Hamas’ military activity… The Senate is convinced that the Petitioner sympathizes with the goals of Hamas.” [8]

Netherlands

A similar story unfolded in the Netherlands, where the Minister of Foreign Affairs issued an administrative order in April 2003 freezing the assets of Stichting al-Aqsa in Heerlen. As in Germany, the Dutch decision invoked the authority of national anti-terror legislation adopted in the wake of 9/11.

Stichting al-Aqsa responded to the ban by filing suit against the Dutch government. After reviewing classified evidence from Dutch security services, the court ruled that the government was justified in its decision to freeze Stichting al-Aqsa’s assets. [9]

Stichting al-Aqsa later filed suit in the EU court system, arguing that it had not been given a fair opportunity to contest its inclusion on the EU terror list. In July 2007, the European Court of First Instance agreed with al-Aqsa’s argument, ruling that the freezing of al-Aqsa’s assets in the Netherlands had been illegal.

The EU responded by modifying its procedures for making changes to the EU terror list and simply de-listing and re-listing Stichting al-Aqsa. In a case that is still pending, Stichting al-Aqsa filed suit against the European Council in July 2008, seeking more than 10 million euros as compensation for its inclusion on the EU terror list.

Belgium

Although Belgian security forces told Federal Parliament in 2002 that they believed Hamas was present in Belgium through al-Aqsa in Verviers, no official effort to shutter the organization has been undertaken. [10] While al-Aqsa e.V. and Stichting al-Aqsa both appear on the EU terror list, al-Aqsa’s offices in Verviers and Brussels do not. A Belgian parliamentarian testified in January 2004 that there was insufficient evidence to place the Belgian organization on the list. [11]

After the German court ruled definitively in December 2004 that the government had been correct in banning al-Aqsa e.V. in Aachen, Mahmoud Amr withdrew from the board of al-Aqsa Humanitaire in Belgium and the organization changed its name to Aksahum. [12]

Conclusion

These cases illustrate the complexities of prosecuting cases of suspected terrorist financing through charities and the specific challenges created by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At a basic level there is an unenviable policy trade-off between the imperatives of permitting humanitarian aid and preventing terrorist financing. The situation is exacerbated by the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories and Hamas’ abuse of charities. The cases at hand have been particularly difficult to prosecute, in part due to Hamas’ semi-official standing and widespread support in Gaza. Against this background, both the Swedish and Danish courts argued that the presence of acknowledged Hamas members in a specific charity does not prove that the charity is “part” of Hamas. Such an argument is more difficult to make in countries or regions where only a very small percentage of the population sympathizes with a terrorist group. It is telling that even large government agencies have had trouble ensuring that public funds do not make their way to Hamas. [13]

The trials also show that the way Israeli evidence is evaluated can be central to the final outcome of a case. The importance of Israeli evidence underlines the challenges small countries like Sweden and Denmark face in gathering evidence in terrorist financing cases without the cooperation of government authorities in the recipient/target countries.

The trials of al-Aqsa in Sweden and Denmark demonstrate that the evidentiary threshold for criminal procedures in sanctions cases is very high in those countries. Individuals set on circumventing those laws may find it easier to create plausible deniability in their efforts. In Germany and the Netherlands, administrative bans have enjoyed some success, but the legality of these measures has come up against repeated legal challenges.

Efforts to combat terrorist financing appear to have come full circle, from the silent monitoring and intelligence-gathering exercised pre-9/11 by the U.S. and advocated by Germany in 2002, to the vigorous use of civil and criminal procedures to try to halt the transmission of funds to terrorist organizations. In several countries, however, the judicial challenges of obtaining convictions in terrorist financing cases seem to be swinging the pendulum back towards silent intelligence gathering. The al-Aqsa cases in Sweden and Denmark may further this trend.

Notes:

1. Swedish Al Aqsa case, Court Transcript, Mål nr. B 8056-06 Malmö Tingsrätt, Sweden February 17, 2009.

2. Ibid, p.8.

3. Ibid, p.5.

4. Ibid, pp.5, 7-8.

5. In the Swedish case, the charities were transcribed as Islamic Society and Jenin Charity Committee, whereas in Denmark they were transcribed as Islamic Charitable Society and Zakat Committee Jenin.

6.Danish Court Transcript, Anklagesmyndigheden mod Rachid Mohamad Issad mfl, 10.afd. a.s. nr. S-1057-07 Ostre Landsret, Denmark, February 6, 2008, pp 34-44.

7. https://www.treas.gov/press/releases/js439.htm; For the charters, see Appendix D at https://www.terrorism-info.org.il/malam_multimedia/html/final/eng/sib/1_05/german.htm

8. https://www.imra.org.il/story.php3?id=23782 [German court’s press release – December 3, 2004 – in translation. Press Release no. 69/2004.

9. Judgment of the Court of First Instance, July 11, https://curia.europa.eu/jurisp/cgi-bin/gettext.pl?lang=en&num=79929288T19030327&doc=T&ouvert=T&seance=ARRET

10. Sénat et Chambre des Représentants de Belgique, Session De 2001-2002, Rapport d’activité.2001 du Comité permanent de contrôle des services de renseignements et de sécurité, Juillet 19, 2002, https://www.senate.be/www/?MIval=/publications/viewPubDoc&TID=33618007&LANG=fr

11. Séance Plénière, Compte Rendu Analytique, Chambre des Représentants de Belgique/Beknopt Verslag, Belgische Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers, January 28, 2004, https://www.dekamer.be/doc/CCRA/html/51/ac140.html

12. Tribunal de Commerce de Verviers, June 13, 2007, https://www.cass.be/tribunal_commerce/verviers/images/1306.0009.pdf

13. C.f. Matthew Levitt, “Better late than never – Keeping USAID funds out of Terrorist Hands,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2007 https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/templateC05.php?CID=2653