Evidence of the Chinese Central Government’s Knowledge of and Involvement in Xinjiang’s Re-Education Internment Campaign

Evidence of the Chinese Central Government’s Knowledge of and Involvement in Xinjiang’s Re-Education Internment Campaign

Introduction

Documents leaked to the New York Times (also known as the Xinjiang Papers) in November 2019 revealed how Chinese President Xi Jinping laid the groundwork for the Chinese government’s draconian campaign of internment in the northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). In April 2014, while visiting the region, Xi demanded an all-out “struggle against terrorism, infiltration and separatism” that showed “absolutely no mercy.” He likened Islamic extremism to a virus, noting that its eradication would require “a period of painful, interventionary treatment” (New York Times, November 16, 2019). But more direct links between Xinjiang’s re-education internment campaign that began in 2017, and the central government—including Xi himself—have so far remained elusive.

In the absence of such evidence, western expert, media and political commentary on the atrocity has typically placed the responsibility for these policies on the XUAR Party Secretary Chen Quanguo (陈全国), who has been widely referred to as their “architect” (e.g., Bloomberg, September 27, 2018; Shareamerica.gov, July 27, 2020). In July 2020, Chen became the highest-ranking Chinese official to be sanctioned by the U.S. government in connection with “serious rights abuses against ethnic minorities” in the XUAR (U.S. Treasury Department, July 9, 2020), but other central government figures have escaped such designations. Researchers have refrained from explicitly stating that Chen was implementing a central government blueprint, instead noting that “regional Party Secretary Chen Quanguo himself [may be] the progenitor of increasingly repressive measures now employed in Xinjiang”, or that he may “simply [be] the most ruthless tool by which to implement them” (China Leadership Monitor, May 16, 2018).

Now, previously unanalyzed central government and state media commentary from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) surrounding the introduction of the crucial March 2017 “XUAR De-Extremification Regulation” ([新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例], Xinjiang Weiwuer zizhiqu qu jiduanhua tiaoli, hereafter ‘Regulation’) as well as its October 2018 revision show that several important central government institutions were closely and directly involved in the drafting and even approval of this key legislation. The March 2017 Regulation legalized Xinjiang’s re-education internment campaign in the eyes of the state and directly preceded the campaign’s inception.[1] The October 2018 revision contained blunt mandates for re-education in so-called Vocational Skills Education and Training Centers (VSETC, 职业技能教育培训中心, Zhiye jineng jiaoyu peixun zhongxin, a state euphemism for what are in effect high-security internment camps).

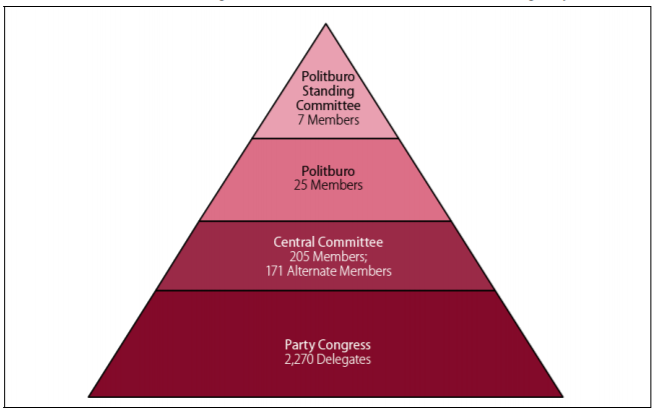

Two of the three central government institutions involved can be directly linked to some of the most powerful members of China’s top decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC, 中国共产党中央政治局常务委员会, Zhongguo Gongchandang Zhongyang zhengzhi ju dangwu weiyuanhui). Specifically, they are overseen by the Politburo Standing Committee’s third- and fourth-ranked members, who rank directly under General Secretary Xi Jinping (first-ranked) and Premier Li Keqiang (second-ranked).

Xinjiang officials have asserted that both the Regulation and the vocational “centers” implement central government policy for the region and the “important instructions” of Xi Jinping (Humanrights.cn, November 23, 2018; Chinaxinjiang.cn, March 31, 2017). Such statements contextualize Xi’s 2020 assertion that “ethnic work [in Xinjiang] has been a success” (Xinhua News, September 26, 2020). Finally, there is substantial circumstantial evidence that when Xi personally addressed Xinjiang’s leadership in March 2017, he spoke in direct relation to the state’s mass interment campaign that would begin weeks later.

While it was always clear that an authoritarian figure such as Xi Jinping, who has presided over the growing centralization of the Chinese party-state since coming to power in 2012, must have at least tacitly approved the PRC’s Xinjiang policy, the extent to which Chen Quanguo may have acted independently—albeit presumably under a generalized central government mandate to bring the region under control—has been unverified. Given Chen’s extensive expertise in previously working to suppress a major restive ethnic group in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), researchers including this author previously speculated that Chen may have both authored and implemented the re-education internment drive (China Brief, September 21, 2017).

Experts have rightly noted that despite the trend toward centralizing control under Xi, the “actual governance of China can be extremely decentralized,” with centrally appointed provincial leaders enjoying substantial degrees of autonomy as long as they align with Beijing’s will (Council on Foreign Relations, June 23). Nevertheless, the new evidence for the more specific and immediate involvement of central government institutions, coupled with official commentary on linkages between regional policies and the will of the central government, may serve to reframe the discussion on the evolution of the Chinese state’s 2017-2019 internment campaign in Xinjiang.

Central Government Involvement in the Drafting of the March 2017 Regulation

The March 2017 De-Extremification Regulation laid the foundation for the “normalization, standardization, and legalization” (常态化、规范化、法治化, changtaihua, guifanhua, fazhihua) of Xinjiang’s re-education (lit. “transformation through education”—教育转化, jiaoyu zhuanhua) through “centralized education” involving “behavioral correction” (XUAR Government, March 30, 2017; Legal Daily, April 11, 2017). Re-education camp construction bids and anecdotal accounts from the ground indicated that Xinjiang’s campaign of mass internment began right around when the Regulation came into effect.[2] The PRC has also stated that the Regulation constitutes the legal basis for the VSETC (PRC Consulate-General in Brisbane, November 30, 2018). The Regulation was revised in October 2018 to fully legitimize the VSETC, referring to them as “re-education institutions” (教育转化机构, jiaoyu zhuanhua jigou) (Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress, October 9, 2018). Construction bids for such “centers” were already being published by the fall of 2017.[3]

An April 11, 2017 article published by Legal Daily (法制日报, Fazhi Ribao), a newspaper backed by the state’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission (CPLC, 中央政法委, Zhongyang zheng fa wei) that describes itself as “the party’s main mouthpiece on the political and legal front,” noted that the drafting of the Regulation took “over two years” (Legal Daily, April 11, 2017; Legal Daily, August 1, 2020; China Court, April 6, 2017). The process involved extensive consultations (lit. “extensively solicited opinions”, 广泛征求意见, guangfan zhengqiu yijian) with three important central government organs: the Office of the Central Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group (中央新疆工作协调小组办公室, Zhongyang Xinjiang gongzuo xietiao xiaozu bangongshi, often shortened to 中央新疆办, Zhongyang Xinjiang ban); the Legislative Affairs Commission of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) (全国人大法工委, Quanguo renda fa gong wei), and the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA, 国家宗教局, Guojia zongjiao ju) (Legal Daily, April 11, 2017).

Legal Daily’s information came from Qin Wei (秦维), director of the Legislative Affairs Commission of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress (自治区人大常委会法制工作委员会, Zizhuqu renda chang wei hui fazhi gongzuo weiyuanhui), who was closely involved in the drafting process (Turpan City People’s Government, September 1, 2016). Qin added that besides these three central government institutions, more than 20 relevant departments and bureaus in Xinjiang were also involved. In May 2016, when Qin discussed the review of a preliminary draft of the Regulations at the 22nd meeting of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress, he stated that both the national Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee (中国共产党中央委员会, Zhongguo Gongchandang zhongyang weiyuanhui, often shortened to 党中央,dangzhongyang) and the regional XUAR version of that body “attach great importance to the work of de-extremification,” and that both had proposed “a series of major deployments and decisions” (XUAR People’s Government, May 26, 2016).

The nature of the involvement of the Central Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group is further clarified in a Work Report of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress published in January 2017 by Tianshan Net:

During the deliberation process of implementing the Counter-terrorism Law and the De-radicalization Regulation, in accordance with the instructions of the [XUAR] Party Committee, it [the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress] also specially reported to the Office of the Central Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group for guidance, [to] ensure that the legislative work transformed the party’s propositions into legal norms that all people abide by (Phoenix Information, January 13, 2017) (emphasis added).[4]

The 2018 revision of the Regulation involved an even more direct link with the central government. The revision process is described in a previously unexamined “Explanation” (说明, shuoming) of the Regulations, published only as an appendix to a related communique of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress (新疆维吾尔自治区人民代表大会常务委员会, Xinjiang Weiwuer Zizhuqu renmin daibiao dahui changwu weiyuanhui). The Explanation states that:

Relevant leaders of the Party Committee of the Autonomous Region, relevant leaders of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress and relevant comrades of the Legislative Affairs Commission made a special trip to the Legislative Work Commission of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress [in Beijing] to report on the revision. The Legislative Affairs Commission of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress expressed its full affirmation of the role of the autonomous region’s local laws and regulations in counterterrorism and stability maintenance work, expressed approval for the amendments to the “Regulation”, and proposed specific amendments to form a draft amendment, which was reported [back] to the autonomous region’s Standing Committee of the Party Committee for review and approval (XUAR People’s Congress, September 10, 2018).[5]

The deliberations of the revisions made by the NPC apparently took place during the 21st meeting of the directors of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress in August 2018 (Xinjiang Daily, August 11, 2018).

The close involvement of these central government institutions in the drafting of the Regulation and its 2018 revision (in the case of the NPC) is of extreme significance.

The chairman of the NPC Standing Committee (currently Li Zhanshu, 栗战书) to whom the Legislative Affairs Commission reports, is the third-ranked member of the PSC, (Congressional Research Service, March 20, 2013). Wang Yang (汪洋), head of the Central Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group, is the fourth-ranked member of the PSC, and also chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC; 中国人民政治协商会议全国委员会, Zhongguo renmin ghengzhi xieshang huiyi quanguo weiyuanhui), which represents a central part of the CCP’s United Front system (China Leadership Monitor, May 16, 2018).[6] The PSC consists of seven members and is China’s supreme decision-making body, more powerful than the Politburo itself.

Practically speaking, the direct and close involvement of the NPC Standing Committee’s Legislative Affairs Commission and the Central Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group in the drafting of the 2017 Regulation (and the Legislative Affairs Commission’s further involvement in its 2018 revision) provides tangible evidence that the framing of Xinjiang’s de-extremification through re-education campaign was undertaken with the direct knowledge of leading figures in China’s most powerful policy, legislative and advisory bodies (see Figure 1). This effectively implicates Xi’s inner circle of power in the atrocities committed in Xinjiang.

In addition, the new findings shed further light on the involvement of Hu Lianhe (胡联合), who defended Xinjiang’s re-education campaign at the United Nations in Geneva in August 2018 following China’s first admission of the existence of vocational “centers.” Hu has been a deputy director of the Office of the Central Committee Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group since 2012 (China News, July 17, 2017; China Brief, October 10, 2018). The close involvement of his institution means that Hu would have been involved in the entire two-year drafting of the Regulation. This strengthens the link between this pivotal figure in the central government and the Xinjiang re-education campaign.

In May 2017, it was revealed that the powerful and secretive United Front Work Department (UFWD) had created a “Ninth Bureau” (九局, jiu ju) to be responsible for implementing central government decisions regarding Xinjiang work (Global Times, May 4, 2017; China Brief, May 9, 2019). Media reports noted that the office’s leaders, including Hu Lianhe, then serving as one of the Ninth Bureau’s deputy directors, had de facto begun their work several months prior (Creaders.net, July 14, 2017; Hohai University, October 29, 2015).

Attributions to the Central Government During the Introduction of the March 2017 Regulation

On March 31, 2017, the day before the Regulation came into effect, the General Office of the Standing Committee of the XUAR People’s Congress held a press conference:

[It was] emphasized that the Regulation … constitutes the implementation of the central government’s policy decisions and deployments, especially to implement the important instructions and requirements of General Secretary Xi Jinping… (Chinaxinjiang.cn, March 31, 2017).[7]

This important statement clarifies at the highest relevant official level in Xinjiang that the interactive drafting process of the Regulation and its revision between the legislative committees of the XUAR People’s Congress and the National People’s Congress in Beijing had implemented the policies of the central government. The specific emphasis that the Regulation is “especially” related to implementing Xi’s own “instructions and requirements” is of high significance. The reference to the “important instructions and requirements of General Secretary Xi Jinping” likely refers to an important speech made by Xi to Xinjiang’s top leaders at the March 2017 Two Sessions in Beijing, just weeks prior to the onset of the internment campaign.

Such a direct link between the legal regulations underpinning and justifying the re-education campaign and the central government is uncommon and has until now escaped wider notice outside of China. It was likely designed to legitimize the unusual and extreme measure and was in fact followed by stern exhortations that “all regions, departments, and units in Xinjiang must … earnestly study and publicize the Regulation, strictly implement the Regulation, and fully implement their duties and responsibilities” (Chinaxinjiang.cn, March 31, 2017). It may also have been an attempt by the Xinjiang authorities to clarify that this measure was ordered by Beijing, and not merely a matter of local initiative.

The same pattern of first linking the Regulation to the central government and Xi Jinping and then issuing stern warnings regarding its unconditional implementation can be found in an April 2020 notice issued by the XUAR Discipline Inspection Commission (自治区纪委监委, zizhiqu jiwei jianwei). It states that “the Regulation is a major measure taken by the autonomous region to implement the CCP Central Committee’s strategy of governing Xinjiang, with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core” (XUAR Discipline Inspection Commission, April 6, 2020).[8] It then emphasizes:

It is necessary to earnestly shoulder the responsibilities, strengthen supervision and inspection of the implementation of the Regulation, increase the intensity of conducting thorough investigations, identify [problems] early, identify [problems when they are] minor, punish at every turn, discover problems, deal with them seriously, [in order to] create deterrents (XUAR Discipline Inspection Commission, April 6, 2020).

The New York Times’ Xinjiang Papers indicated that some leading officials initially refused to fully implement the internment drive, with one county even releasing some detainees. This new evidence indicates that the state anticipated such issues and issued preemptive warnings couched in language that justified the measure by emphasizing that it represented a crucial implementation of the will of the central government, even citing Xi himself.

Legitimizing the Internments: Links between the Vocational “Centers” and the Central Government

In August 2017, when the mass internment campaign was in full swing, Meng Jianzhu (孟建柱), then-secretary of the CPLC, inspected “prisons and detention centers [in the XUAR] many times to learn about the education and reform of criminals and the management of detainees,” according to a media report published by the PRC’s top judicial body (PRC Supreme People’s Court, August 28, 2017). He probably also visited re-education camps, but China had not yet publicly admitted the existence of such camps when the above mentioned media report was published, and such details were therefore likely omitted. Meng “fully affirm[ed] Xinjiang’s remarkable achievements in the fight against terrorism” and emphasized the necessity to “thoroughly implement the CCP Central Committee’s Xinjiang Strategy and General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important instructions on Xinjiang Work” (PRC Supreme People’s Court, August 28, 2017). Based on the evidence presented so far, Meng’s statements can be understood as a central government affirmation that Xinjiang’s re-education internment campaign was proceeding as planned.

Similar affirmations of the campaign’s success in line with central government expectations can be found later on, when the internment drive and its socio-economic impact was likely close to a climax. In November 2018, one month after the revised Regulations were published, Nurlan Abdumanjin, chairman of the XUAR People’s Political Consultative Conference (新疆维吾尔自治区政协主席, Xinjiang Weiwuer Zizhiqu zhengxie zhuxi) and also a member of the 19th CCP Central Committee, which consists of the nation’s leading figures (中国共产党第十九届中央委员会, Zhongguo Gongchandang di shijiu jie zhongyang weiyuanhui; see Figure 1), directly linked the re-education internment campaign with the central government and Xi himself (Humanrights.cn, November 23, 2018). With surprising bluntness, Abdumanjin stated:

[C]arrying out Vocational Skills Education and Training work [the camps] in accordance with the law [i.e. the revised Regulation] is an important measure to implement the CCP Central Committee’s strategy of governing Xinjiang, with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core.[9]

At this time, the internment drive would have had a severe impact on the society and economy of the XUAR. It would have been important to legitimize the extreme policy as an “important measure” for implementing the central government’s Xinjiang work. Otherwise, the population may have wondered whether the internment drive was an excessive aberration perpetrated by regional authorities.

Another close link between the camps and the central government can be found in a November 2018 report on a discussion between lecturers and students at Xinjiang University, the region’s most prestigious academic institution, about the visit of eight lecturers to several Vocational Skills Education and Training Centers in southern Xinjiang (Xinjiang University, November 22, 2018). Written when international criticism of the camps was still muted, the report is exclusively for internal consumption. It wastes no time portraying the “centers” as benign and makes no effort to describe their conditions, instead focusing on their “urgent necessity” for achieving de-extremification work. Crucially, the participants’ response to the presentations is described as follows:

Everyone [all present lecturers and students] believes that the establishment of the Vocational Skills Education and Training Centers is a major measure taken by the Party Committee of the Autonomous Region to implement the CCP Central Committee’s strategy of governing Xinjiang…[10]

The wording of the section related to implementing the central government’s Xinjiang governance is almost identical to Nurlan Abdumanjin’s comments. It clearly indicates that the internment measures were a direct implementation of Beijing’s will (and therefore fully legitimate), and that this was actively communicated to society, which now fully “believes” in its necessity. With Beijing actively behind the campaign, it would have been clear to Xinjiang’s population that any resistance is futile.

A third article, published on the online portal of Guangming Daily, a propaganda outlet of the CCP Central Committee and re-posted on various private news websites, similarly argues that:

[T]his training [in the VSETC] … embodies the CCP Central Committee’s strategy of governing Xinjiang with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core (Chinaxinjiang.cn, October 22, 2018). [11]

Its publication date, October 22, 2018, indicates that around the time of the revised Regulation—possibly near the peak of the internment campaign in terms of total detainee figures—there was a concerted effort to popularly legitimize this campaign by linking it with the will of Xi and the central government.

Final Affirmation: the “Success” of Xinjiang’s De-Extremification Work

In July 2019, when Xinjiang began to release growing numbers of vocational camp detainees, the success of the state’s Xinjiang work was affirmed by XUAR governor Shohrat Zakir. Zakir referred to a speech given by Xi Jinping in March 2017 to the Xinjiang delegates at the Two Sessions, which are China’s highest-level annual legislative sessions that took place only weeks before the start of the internment campaign. Zakir said:

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China [in 2012], the CCP Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core has attached great importance to Xinjiang Work … and has devoted a lot of effort to Xinjiang Work. General Secretary Xi Jinping personally went to Xinjiang to inspect and guide the work, presided over many meetings to study Xinjiang Work, delivered a series of important speeches, and issued a series of important instructions…During the nation’s ‘Two Sessions’ in 2017, General Secretary Xi Jinping personally attended the Xinjiang delegation to participate in the deliberations and delivered an important speech, putting forward earnest expectations for Xinjiang Work, providing fundamental adherence to and injecting strong impetus into Xinjiang Work. We have fully implemented the Party’s strategy for governing Xinjiang … earth-shaking changes have taken place… (PRC Embassy in Canada, July 31, 2019) [12] (emphasis added)

A similar and even more direct link between Xi’s March 2017 speech and the successful implementation of the central government’s Xinjiang Work is found in a February 2019 China Daily article titled, “Xinjiang implements General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important speech at the nation’s Two Sessions”:

On March 10, 2017, when General Secretary Xi Jinping participated in the deliberations of the Xinjiang delegation of the nation’s Two Sessions [he] emphasized that it is necessary to tightly embrace the general goal of social stability and long-term peace and stability…

In the past two years, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Party Committee and government have resolutely implemented the important instructions of General Secretary Xi Jinping, focused on the overall goal, made ‘strings of efforts’, dared to be dauntless, fought tough battles, … and created a new horizon in Xinjiang Work (China Daily, February 26, 2019).[13]

In both Zakir’s speech and the China Daily report, this succession of statements is highly significant: it directly links Xi’s March 2017 speech to the successful implementation in Xinjiang of his instructions between 2017and 2019.

More details of Xi’s speech are recorded in other state media articles. For example, Xi is quoted as saying that “we must insist on maintaining stability as a political responsibility, identify [problems] early, identify [problems when they are] minor, grasp quickly, grasp well, seek long-term strategies, act to consolidate the foundation” (XUAR People’s Congress , September 28, 2020). State media photos show that both Xinjiang’s Party Secretary Chen Quanguo and governor Shohrat Zakir attended the March 2017 Xi speech (Xinhua, March 11, 2017).

Xi’s emphasis on the long-term implementation and consolidation of de-extremification is in line with the essence of the 2017/2018 Regulation. Chinese scholars have also noted that the VSETC represent an institutionalization of de-extremification work.[14] Xi’s exhortation that Xinjiang’s officials must grasp this work early, quickly, and well is echoed in the Xinjiang’s government’s public statements.

It was argued at the press conference introducing the Regulation in March 2017 that the Regulation constituted an implementation of the “important instructions and requirements of General Secretary Xi Jinping” (Chinaxinjiang.cn, March 31, 2017). The above mentioned February 2019 China Daily article repeats some of this wording verbatim when it refers to the “important instructions of General Secretary Xi Jinping,” before stating that such instructions were implemented in Xinjiang between 2017 and 2019 (China Daily, February 26, 2019). References to Xi’s unpublished speech on Xinjiang work at the March 2017 Two Sessions imply that it is possible—and even likely—that Xi himself endorsed the re-education campaign just weeks prior to its inception. In the author’s view, it is likely that Xi exhorted Xinjiang’s officials to unconditionally implement the new measures. In any case, according to Zakir, Xi closely aligned himself to the unconditional implementation of Xinjiang Work in the context of the imminent launch of the re-education campaign in March 2017.

Zakir’s positive assessment of Xinjiang’s faithful implementation of the central government’s strategy for the region was also affirmed by Xi Jinping himself in a September 2020 speech at the Third Central Xinjiang Work Forum. Xi said, “Xinjiang is enjoying a favorable setting of social stability… The facts have abundantly demonstrated that our national minority work has been a success” (Xinhua, September 26, 2020).

Conclusion

The evidence presented above demonstrates that central government institutions were directly involved in the drafting of the legal foundation for Xinjiang’s re-education internment campaign, which included defining the specific role of the VSETC. Xinjiang’s population was told that the region’s policies on re-education and de-extremification, including the “vocational” camps, were undertaken in fulfillment of the central government’s policies and strategies, with “Xi Jinping at the core.” Given the additional and previously untranslated reports on Xi’s March 2017 speech, it is possible that Xi himself confirmed or ordered this draconian approach just weeks before its implementation.

The author has previously argued that Chen Quanguo’s rapid security build-up, which led to a campaign of mass internment just nine months after he became Xinjiang’s party secretary, was almost certainly based on a premeditated plan (Journal of Political Risk, February 17, 2020). The author surmised that Chen, his predecessor Zhang Chunxian (张春贤) and Xi Jinping could all have been present and laid the groundwork for this activity at the March 2016 Two Sessions. We now know that this would have taken place during the middle of the two-year drafting period of the Regulation, likely at a time when this enormous undertaking would have already been planned, ahead of its successful execution one year later.

Official commentary emphasizes that the 2017 Regulation and its 2018 revision—representing the legal framework for the internment camps—are “local regulations” (地方性法规, difang xing fagui) that follow “local legislative procedures” (地方立法程序, difang lifa chengxu) (Chinacourt.org, April 6, 2017). This is likely an attempt to divert attention away from the central government’s role in formulating Xinjiang Work, strengthening the argument that extremism is a regional problem that is being addressed through local solutions. Governor Zakir expressed this logic succinctly in an October 2018 interview with Xinhua, following the publication of the revised Regulation and the acknowledgement of the existence of the vocational “centers”:

While strictly following the Constitution, the law on regional ethnic autonomy and the legislation law, Xinjiang has taken its local conditions into consideration and [itself] formulated the region’s enforcement measures of the … de-extremization regulations… (Xinhua, October 16, 2018).

Zakir’s carefully crafted framing of the internment camps as a local solution (omitting the close involvement of institutions such as the NPC) has helped to divert some of the blame from Beijing and has been so far successful in ensuring that international sanctions responding to the human rights violations associated with the camps have focused on Xinjiang officials.

Based on the new evidence, the author suggests a new understanding of the development and implementation of the internment campaign. Xinjiang’s previous party secretary Zhang Chunxian experimented with re-education practices that were administered first in villages and then, especially after Xi’s pertinent remarks and demands in 2014, implemented in dedicated “transformation through education” facilities (China Brief, May 15, 2018). In 2015, the region began drafting what would become the 2017 Regulation on De-Extremification. It likely did so based on a specific central government mandate to develop a long-term solution to tackling local ethnic dissent. The Xinjiang government was formally in charge of drafting the Regulation—while also continuing to implement and experiment with actual re-education practices—but the new evidence shows that this drafting was done in close consultation with and contingent on the approval of central government institutions. This supports the author’s prior assessment that when Chen Quanguo replaced Zhang Chuxian in mid-2016, he essentially took charge of an ongoing and already premeditated process (Journal of Political Risk, February 17, 2020). Rather than being the primary architect of the re-education internment campaign, Chen was most likely brought in to implement a plan that had largely been outlined and approved by the central government, based on prior experimentation with re-education in Xinjiang.

The central government has been able to claim that the re-education campaign constitutes a local solution to a local problem, of which it broadly approves. However, based on the information presented above, the most logical conclusion is that the responsibility and therefore culpability for this campaign rests primarily with the central government, most notably the Politburo Standing Committee. While Chen Quanguo may have substantially contributed to the precise implementation of the re-education internment drive, his role is probably best assessed as that of an executor—not originator—of central government policy decisions.

The new evidence outlined in this article could serve to determine a much greater level of Beijing’s culpability for these atrocities.[15] It enhances the potential to establish individual responsibility for involved officials under various modes of liability under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), such as ordering, indirect commission, co-perpetration, or complicity.[16] Although China is not an ICC member state, other modes of liability under customary international law could also be applicable, such as the various forms of joint criminal enterprise applied at the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) or Rwanda (ICTR).

Editor’s Note: This article was updated on December 10, 2021 to correct the name of the “Central Committee Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group” to “Central Xinjiang Work Coordination Small Group”

Dr. Adrian Zenz is a Senior Fellow in China Studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, Washington, D.C. (non-resident), and supervises PhD students at the European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal, Germany. His research focus is on China’s ethnic policy, public recruitment in Tibet and Xinjiang, Beijing’s internment campaign in Xinjiang, and China’s domestic security budgets. Dr. Zenz is the author of Tibetanness under Threat and co-editor of Mapping Amdo: Dynamics of Change. He has played a leading role in the analysis of leaked Chinese government documents, to include the “China Cables” and the “Karakax List.” Dr. Zenz is an advisor to the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, and a frequent contributor to the international media.

Notes

[1] Legal experts have pointed out that Xinjiang’s detentions for re-education can only be legalized through a formal statute passed by the NPC or its standing committee, meaning that Xinjiang’s local legislation is by itself insufficient (Lawfare, October 11, 2018).

[2] Adrian Zenz, “’Thoroughly reforming them towards a healthy heart attitude’: China’s political re-education campaign in Xinjiang,” Central Asian Survey, 38:1, 2019, first published September 5, 2018, 102-128, doi: 10.1080/02634937.2018.1507997.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Original Text: “实施反恐怖主义法办法、去极端化条例的审议过程中,还根据党委的指示专报中央新疆工作协调小组办公室请求指导,确保立法工作把党的主张转化为全民共同遵守的法律规范” (Phoenix Information, January 13, 2017).

[5] Original Text: “自治区党委有关领导、自治区 人大常委会有关领导和法工委有关同志, 专程前往全国人大常委会法工委汇报修 改情况。全国人大常委会法工委对自治 区地方性法规在反恐维稳工作中发挥的 作用表示充分肯定,对《条例》的修改表示 赞同,同时提出了具体的修改意见,形成 修正案草案,并报经自治区党委常委会研 究同意” (XUAR People’s Congress, September 10, 2018).

[6] Wang Yang’s predecessor was Yu Zhengsheng (俞正声) (Gov.cn, April 3, 2014).

[7] Original Text: “乃依木·亚森强调,《条例》是新疆首部去极端化方面的地方性法规,也是依法治疆、建设法治新疆的一项重要立法。是贯彻落实中央的决策部署,特别是贯彻落实习近平总书记的重要指示和要求…” (China Xinjiang, March 31, 2017). Compare a similar statement published by the WeChat account of the Xinjiang People’s Broadcasting station on the same day: “全区要充分认识开展“去极端化”工作是以习近平同志为核心的党中央的党中央做出的重要决策部署” (FreeWechat, March 31, 2017).

[8] Original Text: “制定《条例》是自治区贯彻落实以习近平同志为核心的党中央治疆方略的重大举措” (XUAR Discipline Inspection Commission, April 6, 2020).

[9] Original Text: “依法开展职业技能教育培训工作,是贯彻落实以习近平同志为核心的党中央治疆方略、实现新疆社会稳定和长治久安总目标的一项重大举措” (Humanrights.cn, November 23, 2018). For Nurlan Abdumanjin’s biography and credentials, see: https://politics.cntv.cn/2013/11/21/ARTI1385013775952399.shtml. Archived version available at: https://archive.is/wip/xV8rz).

[10] Original Text: “大家认为举办职业技能教育培训中心是自治区党委贯彻党中央治疆方略的重大举措,是实现新疆工作总目标进程中的积极探索和成功范例,坚信在新疆稳定发展中将日趋彰显其巨大作用.” (Xinjiang University, November 22, 2018).

[11] Original Text: “新疆职业技能教育培训…这一培训符合目前新疆反恐维稳和去极端化的工作实际,更在于这一培训体现了以习近平同志为核心的党中央治疆方略” (Chinaxinjiang.cn, October 22, 2018). For the described characterization of Guangming Net, run by Guangming Daily, see (Baidu Baike, accessed September 14).

[12] Original Text: “党的十八大以来,以习近平同志为核心的党中央高度重视新疆工作,心系新疆各族人民,对新疆工作倾注了大量心血。习近平总书记亲自到新疆视察指导工作,多次主持会议研究新疆工作,发表一系列重要讲话、作出一系列重要指示。…2017年全国“两会”期间,习近平总书记亲临新疆代表团参加审议并发表重要讲话,对新疆工作提出殷切期望,为新疆工作提供了根本遵循、注入了强大动力。我们全面贯彻落实新时代党的治疆方略,紧紧围绕社会稳定和长治久安总目标,团结带领全区各族干部群众,真抓实干、攻坚克难,天山南北发生了翻天覆地的变化” (PRC Embassy in Canada, July 31, 2019).

[13] Original Text: “2017年3月10日,习近平总书记参加全国两会新疆代表团审议时强调,要紧紧围绕社会稳定和长治久安总目标 …。两年来,新疆维吾尔自治区党委、政府坚决贯彻落实习近平总书记重要指示,聚焦总目标,打好“组合拳”,敢啃硬骨头,善打攻坚战,…开创了新疆工作新局面。” (China Daily, February 26, 2019).

[14] Zhao Xuan (赵璇), “The Implementation and Conduct of Xinjiang ‘De-Extremification’ Work” [新疆‘去极端化’工作的进程和举措], Xinjiang University School Paper—Philosophy, Humanities and Social Sciences Edition (新疆大学学报 [哲学人文社会科学版]) 47(02) 2019, Xinjiang University Politics and Public Administration Institute (新疆大学政治与公共管理学院), https://bit.ly/38QI9W4.

[15] The following assessment was kindly provided to the author by Erin Rosenberg, a specialist in international criminal law, currently a Visiting Scholar with the Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights, and a former Senior Advisor to the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the U.S. Holocaust Museum.

[16] See Article 25 of the Rome Statute, available at https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf.