‘Fight Them Until There Is No Fitnah’: The Islamic State’s War With al-Qaeda

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 4

By:

Recent events have raised fresh questions over the relationship between the Islamic State militant group and al-Qaeda. For instance, militants from the Islamic State and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the group’s Yemen-based franchise, are reported to have coordinated the multiple jihadist attacks in Paris in early January 2015. Moreover, recent U.S. airstrikes in Syria have targeted both Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s official local franchise, which could potentially push the two groups to unite against the Western threat. Western media reports have also suggested that there have been meetings between Islamic State and al-Qaeda leaders during the past year, aimed at solving the groups’ differences in order to better fight the West (Daily Beast, November 11, 2014; Guardian, September 28, 2014). At the same time, however, the Islamic State’s official online magazine Dabiq shows that many important ongoing differences remain between the manhaj (methodology) of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. The aim of this article is to explore the interplay between the two groups and to show how this relationship may evolve in the coming months.

The Battle Over Takfir

The split within the Islamic State and al-Qaeda dates back to historical differences between Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (killed in 2006), Ayman al-Zawahiri of al-Qaeda and Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi (a.k.a. Asim Tahir al-Barqawi), a prominent Salafi-Jihadist Jordanian ideologue who had been Zarqawi’s original mentor, over how to deal with the issues of Shi’a Muslims and when to pronounce takfir (excommunication) against Muslims in general. [1] This dispute, which combined both strategy and ideology, was triggered by al-Zarqawi’s indiscriminate attacks on Iraqi Shi’a civilians in the 2003-2006 period, which prompted Zawahiri to write him a letter in July 2005, asking: “And can the mujahideen kill all of the Shi’a in Iraq? Has any Islamic state in history ever tried that? And why kill ordinary Shi’a considering that they are forgiven because of their ignorance?” This letter further suggested Iran and al-Qaeda should not fight each other since their joint enemy is the West. [2] An important outcome of this dispute is that al-Qaeda remains generally much more reluctant to declare takfir against fellow Muslims en masse than the Islamic State, which is quicker to regard all Muslims who have not pledged loyalty to the group as apostates. These differences were underlined in April 2014, when the Islamic State’s spokesperson Shaykh Abu Muhammad al-Adnani issued an audio message called “This was never our manhaj and will never be,” an extensive criticism of al-Qaeda’s marginally less hardline doctrines. [3]

Since then, the Islamic State has continued to seek to discredit al-Qaeda leaders as well as scholars with whom they have allegedly cooperated, such as AQAP member Shaykh Harith al-Nadhari, who was killed in an American drone strike in February and who had been a vocal critic of the Islamic State (BBC, February 5). For instance, he is pictured in the sixth issue of Dabiq, together with other AQAP leaders, and is described as “void of wisdom.” [4]

Paris Attacks

Initially, when the attacks on the Charlie Hebdo magazine and Jewish targets in Paris were carried out on January 7-9, both supporters of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State celebrated these as revenge for perceived attacks on the honor of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad. However, the latest evidence suggests that the attacks were made possible by personal connections between the two sets of attackers, Islamic State-inspired Amedy Coulibaly and al-Qaeda-linked Chérif and Said Kouachi, who were both influenced by the France-based al-Qaeda recruiter Djamel Beghal (Wall Street Journal, January 13). Further muddying the waters, Islamic State-supporter Amedy Coulibaly said in a video before the attacks that he had coordinated the Paris operations with the Kouachi brothers and AQAP militants (Daily Beast, January 11). However, senior AQAP official Nasser bin Ali al-Ansi, who claimed responsibility for the Charlie Hebdo attack, said it was a mere coincidence that the operations of the Kouachi brothers had coincided with the attack by Ahmed Coulibaly (Telegraph, January 14). It was therefore no surprise that al-Ansi was criticized in the seventh edition of the Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine as being hizbiyyin (partisan) in favor of al-Qaeda. [5] Dabiq’s sixth issue also said that although Coulibaly, who attacked the Parisian Jewish targets, helped to finance the brothers, their operations were different. These different views may reflect that among would-be militants in France, the differences between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda are seen as less important than to those in the Middle East.

On the Frontlines in Syria

Meanwhile, on the frontlines in Syria, relations between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda also do not seem to be improving. In early January 2014, the first major clashes erupted between the Islamic State and other rebel fractions, including al-Nusra (Daily Star [Beirut], February 24). This led to the killing of Abu Khaled al-Suri, the co-founder of the Ahrar al-Sham Islamist group who had long-standing ties to al-Qaeda, in late February. Following his death, al-Nusra issued a call to the Islamic State to stop the infighting (al-Akhbar [Beirut], February 26). Despite this, fighting continued on several fronts, especially in the provinces of Aleppo and Deir al-Zor. The only area where both group were present without conflict was the strategic Lebanese border region of Qalamoun, where there was reportedly cooperation between a small number of Islamic State fighters and al-Nusra against Hezbollah and the Syrian government in early 2014 (McClatchy, April 3, 2014). Although this demonstrates the theoretical ability for these groups to cooperate against hated enemies such as Hezbollah, even this limited cooperation apparently takes place reluctantly and only under pressure (al-Akhbar [Beirut], December 26, 2014). On the other hand, even when al-Nusra moved against Western-backed rebels in the Syrian province of Idlib in October 2014, it apparently did not cooperate with the Islamic State (Washington Post, November 2, 2014). [5]

Likewise, after the United States launched airstrikes against the jihadist groups in Syria in September, there were attempts by various jihadist factions to bridge their differences (Middle East Eye, November 14). This was made easier by the fact that the zones of control of the different jihadist factions were more clearly divided after months of infighting. Despite this, a ceasefire offer by the leader of Jaysh al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar to end the bloodshed between the jihadist factions in the face of Western airstrikes was reportedly rejected by the Islamic State leadership in Raqqa in November. The Islamic State further widened rifts by suggesting that jihadist groups fighting against the Islamic State were murtadeen (apostates), just as it has already described other jihadist factions in Syria as apostates. [6]

Similarly, tensions between the rival groups have continued in Syria’s Aleppo province, where the Syrian government has been trying to encircle the city. For instance, in December 2014, al-Nusra supporters claimed that the Islamic State launched multiple attacks against it in northern Aleppo. This offensive predictably disrupted al-Nusra’s ongoing assault on the government controlled Shi’ite villages of Nubul and Zahra. [7] “All this infighting isn’t getting us further in our battle against the Nusayriya [Syrian government] and Rawafid [Shi’a],” wrote Dutch al-Nusra-fighter Abu Muhammad on Twitter in response. [8] There were also suspicions among al-Nusra supporters that the Islamic State was behind suicide attacks carried out against al-Nusra-held checkpoints in Aleppo in January (Aranews, January 11). Despite this enduring rivalry, however, some Islamist militants apparently hope for an end to the strife between the groups, especially after the United States formed a coalition to fight jihadist movements in both Iraq and Syria. For instance, one al-Nusra fighter has told the media: “If all the powers of mujahideen worldwide would be united, this would have significant benefits for the jihad” (Middle East Eye, November 14, 2014).

Burning of Jordanian Pilot

Given that U.S. and coalition airstrikes have targeted both al-Nusra and the Islamic State, one might expect al-Qaeda members to not condemn the burning of Jordanian Air Force pilot Muadh al-Kasasbeh in Syria by the Islamic State. On the contrary, however, Salafi-Jihadist ideologues and allies of al-Qaeda-linked groups in Syria, such as Abdullah bin Muhammad al-Muhaysini and al-Maqdisi, criticized the Islamic State for the action on Jordanian television (al-Ru’ya, February 6). Indeed, such actions exacerbate the fault line between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda; namely, al-Qaeda fears that excessive violence will alienate ordinary Muslims from jihadist groups. In addition, al-Maqdisi had been secretly involved in negotiations to exchange the Jordanian pilot for prisoner Sajida al-Rishawi, who was convicted of involvment in the 2005 Amman bombings. In an interview after the pilot’s death, al-Maqdisi accused the Islamic State of not being serious in its negotiations to free al-Rishawi, leading to her death, as well as strongly criticizing the way in which the pilot was killed: “Then after that I am being surprised with the burning of the pilot… burning? In which sunnah is this? The Prophet forbade this. And you give the precedence to the speech of Shaykh ul-Islam [Ibn Taymiyyah] over him?” [9] Al-Maqdisi further accused the Islamic State of dividing Muslims: “You are splitting the rows of the Muslims and distorting the deen [Islamic religion] by these positions and this slaughtering and this burning.”

In response, the Islamic State argued that the Jordanian government had complicated the negotiations to free the Japanese prisoner Haruna Yukawa by including al-Kasasbeh in the talks, leading to the failure of the negotiations. [10] The Islamic State additionally launched a personal attack on al-Maqdisi, calling him a representative of the Jordanian taghut (tyrant) regime, and describing the Jordanian pilot as an apostate client of al-Maqdisi’s. “Perhaps Allah will facilitate a detailed exposure of how al-Barqawi [al-Maqdisi] (whose campaign of lies carries on) represented the Jordanian taghut in these negotiations,” it added in Dabiq magazine. [11] In response, online supporters of al-Nusra responded by creating a hashtag on Twitter to defend al-Maqdisi. “Every muwahid [onotheist] & mujahid [Jihadist fighter] who stands for the truth; It’s time to stand up & defend Shaykh Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi,” wrote a Dutch al-Nusra fighter on his Twitter-account @Abamuhammed07, underlining that at least some al-Nusra fighters continue to look up to al-Maqdisi. [12]

No Grey Zones

Even before the Paris attacks in January, the December 2014 issue of Dabiq had heavily criticized al-Qaeda, particularly arguing that al-Qaeda (and the Taliban) were too lenient on the Rawafid (Shi’a Muslims and Iran). [13] This issue, therefore, contained two important articles that attack al-Qaeda. “Al-Qa’idah of Waziristan – a testimony from within” by Abu Jarir al-Shamali, a former member of Zarqawi’s Jama’at at-Tawhid wal-Jihad group (that pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda in 2004 and then to the Islamic State in June 2014), criticizes Zawahiri, al-Qaeda’s activities in Afghanistan and Pakistan and the Taliban. In particular, al-Shamali, previously imprisoned for eight years in Iran, blames Zawahiri for not making takfir on Iran, for praising the Arab Spring, for not making takfir on Muslim Brotherhood leaders and for promoting demonstrations instead of armed jihad. “The strangest matter was the hesitance in making takfir of the rafidah [Shi’a] of the era whose evil is not hidden from anyone whether distant or far,” al-Shamali wrote. A separate article in Dabiq by Abu Maysarah al-Shami, meanwhile, attacks the AQAP leadership and blames them for allowing the Shi’a Houthis for taking over Yemen. [14] The author also points out the contradiction between the Taliban’s Afghanistan “emirate” calling for good relations with Iran, while senior AQAP member al-Nadhari calls for “killing the rafidah.” Both articles also criticize al-Qaeda for renewing its allegiance to Taliban leader Mullah Omar in July 2014, with particular complaints being that the Taliban respects international conventions and borders, implements tribal law and is (theoretically) opposed to militant operations outside Afghanistan. The Islamic State’s commitment to these beliefs is not just rhetorical, however; it has consistently sought to put its ideology into practice during the last year, for instance, massacring hundreds of Shi’a soldiers in Tikrit when it started to take control of most of the Sunni areas of Iraq in mid to late 2014 (al-Alam, September 1, 2014).

Conclusion

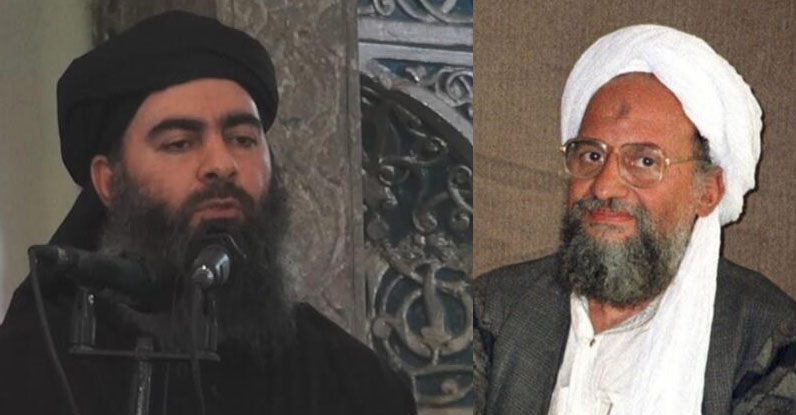

In the February 2015 issue of Dabiq (titled, “From Hypocrisy to Apostasy – The Extinction of the Grayzone”), the position of the Islamic State toward other jihadist factions is made even clearer. [15] In it, the Islamic State quotes Osama bin Laden referring to former U.S. President George W. Bush’s “with us or against us” speech in order to make its position toward other jihadist factions clear: the group’s intention is to clarify that these groups will have to join its self-declared Islamic caliphate or else the Islamic State will fight against them, too. This position underlines that for the Islamic State, al-Qaeda is not Islamic enough, since the group does not consider all Shi’a Muslims to be apostates and thus automatically worthy of death. In this ideological environment, fueled by personal insults against al-Maqdisi and AQAP leaders, any substantial cooperation between the Islamic State and other jihadist factions seems unlikely at present, unless they pledge allegiance to the Islamic State’s caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, or if both sides are so weakened by their rivals on the battlefield that they are forced into a pragmatic compromise. Even in this case, however, such cooperation is unlikely to be enduring.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg is a political analyst specializing in issues concerning Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey with a particular focus on Kurdish politics.

Notes

1 See: Zawahiri’s letter to Zarqawi, July 9, 2005, https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/zawahiris-letter-to-zarqawi-english-translation-2.

2 Ibid.

3. Pieter van Ostaeyen, “Message by ISIS Shaykh Abu Muhammad al-Adnani al-Shami,” April 18, 2014, https://pietervanostaeyen.wordpress.com/2014/04/18/message-by-isis-shaykh-abu-muhammad-al-adnani-as-shami/.

4. Dabiq (Sixth edition), December 2014. Available at: https://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/isis-isil-islamic-state-magazine-issue-6-al-qaeda-of-waziristan.pdf.

5. Dabiq (Seventh edition), February 2015. Available at: https://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/islamic-state-dabiq-magazine-issue-7-from-hypocrisy-to-apostasy.pdf.

6. Joanna Paraszcuk, “Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar Emir Visited IS In Raqqa To Ask For Truce,” From Chechnya to Syria, November 13, 2014, https://www.chechensinsyria.com/?p=22885.

7. See the tweet of Nusra supporter @liwaa38, December 11, 2014, https://twitter.com/liwaa38/status/543017939059101696.

8. See the tweet of Dutch Nusra fighter Abu Muhammad (@Abamuhammed07), February 6, 2014, https://twitter.com/Abamuhammed07/status/563784069365112834.

9. Pieter van Ostaeyen, “Interview and Translation: Shaykh Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi,” February 6, 2015, https://pietervanostaeyen.wordpress.com/2015/02/09/interview-and-translation-shaykh-abu-muhammad-al-maqdisi-dd-february-6-2015/.

10. Dabiq, February 2015, Op. cit.

11. Ibid.

12. See the tweet of Dutch al-Nusra fighter Abu Muhammad, February 14, 2015, https://twitter.com/Abamuhammed07/status/566743465975767040.

13. Dabiq, December 2014, Op cit.

14. Dabiq, February 2015, Op cit.