Fighting the Battle for the Pandemic Narrative: The PRC White Paper on Its COVID-19 Response

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 11

By:

Introduction

On June 7, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) State Council Information Office (国务院新闻办公室, Guowuyuan Xinwen Bangongshi) released an official white paper outlining China’s response to the COVID-19 crisis (Xinhua, June 7). As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve, the document, titled Fighting COVID-19 – China in Action (抗击新冠肺炎疫情的中国行动, Kangji Xinguan Feiyan Yiqing de Zhongguo Xingdong), is a clear articulation as to how the authorities of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hope to control and shape the narratives surrounding their own role in the state response to the virus. Key themes in the report are unsurprising; however, the timeline articulated by the State Council leaves serious questions about the origin of the virus and its initial beginnings.

Several key themes emerge from Fighting COVID-19: China in Action (hereafter, “White Paper”). These include: China’s timely sharing of information with international organizations; narratives of “battle” against the virus; China’s positive international engagement; and the need for economic stabilization. Each of these themes is inter-related. The purpose of the COVID-19 White Paper is for the PRC to “clarify its ideas on the global battle”—a battle that cannot be “won” without international engagement. This is a version of events that emphasizes the “open, transparent, and responsible manner” that China claims to have undertaken throughout the crisis. Yet, alongside assertions of transparency, the document also emphasizes taking actions “in accordance with the law”—which begs the question as to whether key items of information have been omitted in order to justify measures intended to maintain domestic stability (SCIO, June 7).

Timely Notification or Curious Timelines?

According to the White Paper, the official response began on December 27, 2019. On that day, the “Wuhan city government arranged for experts to look into” the cases of viral pneumonia occurring in the city (SCIO, June 7). However, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission had earlier indicated that initial cases of “an unidentified pneumonia outbreak” (肺炎疫情, feiyin yiqing) were identified by December 12, 2019 (China Brief, January 17). The official timeline from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission “reported a cluster of cases of pneumonia in Wuhan” on December 31, 2019, and that “a novel coronavirus was eventually identified.” However, the WHO does not specify any other dates or notes for the month of December (WHO, April 27).

The timeline articulated in China’s COVID-19 White Paper leaves at least two weeks entirely unaccounted for, which raises questions about the interaction between local, national, and international officials. Action at the local level was critical for the identification of this new illness, and several doctors working on the front lines in Wuhan—Li Wenliang, Mei Zhongming, and Jiang Xueqing—have died from the disease (South China Morning Post, March 3). A draft resolution introduced at the World Health Assembly in May—spearheaded by Australia, and now supported by over 110 countries—calls for an “impartial, independent, and comprehensive evaluation” of the events associated with the pandemic (Business Insider, May 18). The PRC has resisted all such calls, and the White Paper reveals a continuing determination to deflect criticism of its early handling of the outbreak. The document calls for the international community to “resist scapegoating or other such self-serving artifices, and [to] stand against stigmatization and politicization of the virus” (SCIO, June 7, Section IV).

Publishing the White Paper is one attempt by the PRC to show that it is “open and transparent” and that “China gave timely notification to the international community” (SCIO, June 7). However, in its present form the White Paper raises significant questions about the initial phase of the outbreak and how information was communicated between local, provincial, and national officials: its timeline begins too late to fully answer these questions, which could hamper efforts to learn the origin of the virus and how it spread initially. A clear understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic began will be necessary for the international medical and scientific community to understand the origins and initial spread of the virus. If the initial days and weeks are not articulated, it may be impossible for epidemiologists, scientists, and policymakers to assess what actually occurred at the outset.

Narratives of Battle

The White Paper makes clear that one of its key goals is to address the “global battle” against COVID-19. The narrative of battle explains both how the PRC “fought” the virus and how the PRC must continue to maintain its story internationally. In terms of the direct fight, according to the White Paper the “all-out battle” against COVID-19 was fought with “confidence and solidarity, [and] a science-based approach and targeted measures.” As a result, after “approximately three months, a decisive victory was secured in the battle to defend Hubei Province and its capital city of Wuhan” (SCIO, June 7).

The “battleground” narrative does two things: it makes the central government look strong in its fight against the pandemic, and shifts focus to the virus as an enemy. Shifting blame is important, because if there is a perception that the central government knew there was an “enemy” lurking in early or mid-December and did not take action, then there would be questions about the government’s decisiveness. Consistent with the “battle” narrative, the White Paper highlights the role of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), stating that 4,000 military medical personnel were dispatched to respond to the crisis, with the PLA Air Force performing important logistical support. The PRC government has also maintained the narrative that no PLA personnel contracted the virus, despite the heavy concentration of PLA forces located in the vicinity of Wuhan (China Brief, April 13).

International Engagement

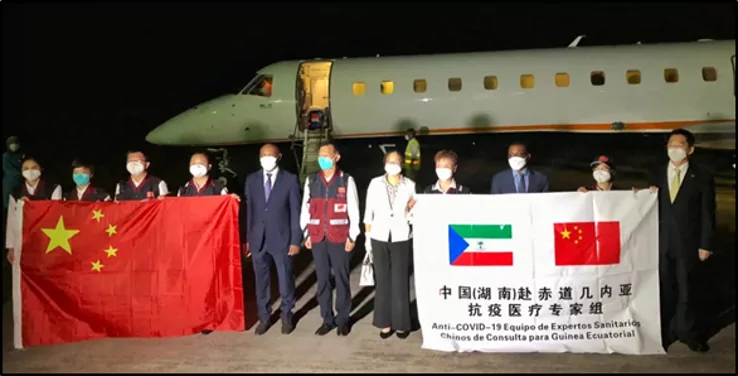

While the “battle” on the ground may have been declared “won” in Wuhan, the battle for the international narrative continues. The White Paper argues that “international solidarity” and “multilateralism” were necessary to deal with the crisis, and highlights these efforts in Section IV of the White Paper, titled “Building a Global Community of Health For All.” Consistent with Xi Jinping’s discourse on the “community of common destiny for mankind” (人类命运共同体, renlei mingyun gongtongti), [1] the White Paper describes how “China has fought should to shoulder with the rest of the world” as part of the idea that “the world is a global community of shared future” (SCIO, June 7).

Like many other PRC government reports in the last decade, the measure of success for international engagement has become a numbers game: how many items can be counted up and measured to show “results”? At the highest level of government, “President Xi has personally promoted international cooperation” by having “phone calls or meetings with nearly 50 foreign leaders and heads of international organizations.” At other levels of government, the PRC has “conducted more than 70 exchanges with international and regional organizations including ASEAN, the European Union, the African Union (AU), APEC, the Caribbean Community, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization” (SCIO, June 7, Section IV).

In addition to top-level meetings, the White Paper promises “US$2 billion of international aid over two years” for a “global humanitarian response depot” in China. The document also outlines tools for sharing scientific information, calls for additional multilateral meetings, and promises assistance for “developing countries with weaker public health systems in Asia, Africa and Latin America – especially Africa” (SCIO, June 7, Section IV).

Economic Stabilization

International engagement and solidarity are major themes of the White Paper, but Beijing acknowledges that global economic cooperation could be heavily impacted by the crisis. The White Paper argues that economic cooperation must continue, while also noting that “the global spread of the pandemic” is “making a severe global economic recession unavoidable” (SCIO, June 7, Section IV). In a move that generated considerable press attention in the United States and Europe, the CCP chose to do away with gross domestic product (GDP) targets at this year’s National People’s Congress (BBC, May 22; Reuters, May 24). However, PRC media outlets claim work will continue on a variety of “sub-targets” that remain necessary for the “building of a moderately prosperous society in all respects” (Xinhua, May 23).

At the international level, the White Paper makes clear that the PRC remains committed to the global economic system. In particular, “China believes that the international community should proceed with globalization, safeguard the multilateral trading system based on the WTO, cut tariffs, remove barriers, facilitate the flow of trade, and keep international industrial and supply chains secure and smooth.” The PRC argues that “COVID-19 is changing the form but not the general trend of economic globalization.” Despite this seemingly optimistic tone, the economic and political challenges of U.S.-China relations over the past several years are not ignored. The White Paper calls out the United States by stating that “Decoupling, erecting walls, and deglobalization may divide the world, but will not do any good to those who themselves are engaged in these acts” (SCIO, June 7).

On the domestic front, the State Council argues that economic stabilization must occur in “employment, finance, foreign trade, inbound investment, domestic investment, and market expectations.” In addition to these “six fronts” for stabilization, the White Paper assigns “six priorities” for social and economic order: “jobs, daily living needs, food and energy, industrial and supply chains, the interests of market players, and the smooth functioning of grassroots government” (SCIO, June 7, Section III). Stabilization in trade will be difficult given the drop in exports (Financial Times, June 7), but China still hopes to attract foreign investment. During the National People’s Congress held in late May, NPC Standing Committee Chairman Li Zhanshu (栗战书) noted that further changes had been made with respect to investment: “After adopting the Foreign Investment Law, we completed its integration with relevant laws by revising a package of laws on construction, fire protection, digital signatures, urban and rural planning, vehicle and vessel taxes, trademarks, unfair competition, and administrative approval” (NPC, May 25).

We do not yet know the full economic toll of the COVID-19 crisis for either China or the global economy, but thus far, China is staying the course. The White Paper reiterated many of the same themes as described in the NPC work report issued in May, which highlighted that “supply-side structural reform and high-quality economic development” remain on the agenda for 2020 (NPC, May 25).

Conclusion: Winning the Battle?

China’s White Paper shows Beijing’s imperative to control the COVID-19 narrative. International engagement is highlighted throughout, but the “battle” is also about the timeline. By focusing on the events that transpired in 2020—rather than the events early in the crisis—Beijing has emphasized the measures to stop the spread of the virus, rather than discussing its origins. Yet, the timeline is critical to future examination of the virus and how it spread. China’s unwillingness to articulate the timing of events in December 2019 undermines the narrative of its “open and transparent” reporting in a timely manner.

For economic recovery and stabilization, the origins of the virus may not matter. Yet, for a full accounting of the disease itself, late 2019 is a critical time period and the current explanations are insufficient. For the good of the “global community of shared destiny,” the PRC may want to evaluate whether the current narrative is complete—and consider how a full accounting of the pandemic requires an accurate and complete timeline of events at all levels of the PRC government.

April A. Herlevi examines China’s political economy and foreign economic policy. She earned her PhD in international relations and comparative politics from the University of Virginia, and currently serves as a research scientist at CNA, a nonprofit research organization in Arlington, Virginia. This work represents her own views, and should not be regarded as representing the opinions of either CNA or its sponsors.

Notes

[1] For analysis of the “community of shared destiny” concept, see: Liza Tobin, “Xi’s Vision for Transforming Global Governance: A Strategic Challenge for Washington and Its Allies,” Texas National Security Review, Vol. 2, Issue 1, November 2018. https://tnsr.org/2018/11/xis-vision-for-transforming-global-governance-a-strategic-challenge-for-washington-and-its-allies/.