The COVID-19 Pandemic Boosts Sino-Russian Cooperation

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 11

By:

Introduction

The immediate impact of the COVID-19 crisis on Sino-Russian relations has been to weaken the social and economic ties between the two states. Similar to circumstances in other countries, their cross-border economic exchanges have abruptly shrunk. The pandemic has also exacerbated xenophobic sentiments in both countries, as well as directing their political leadership inwards towards domestic recovery (China Brief, February 28). However, the COVID-19 crisis has reaffirmed both governments’ ability to manage these challenges and to limit major damage to their relationship. In the long term, the diverging economic performance of the two countries, with China rebounding much faster than Russia, could further increase Russia’s economic dependence on China. Lastly, the crisis has seen a unique convergence of Chinese and Russian narratives, with their reciprocal messaging amplifying their viewpoints. This may foreshadow further cooperation in the information domain between the two countries.

Managing Frictions

The most visible short-term impact of the virus has been to decrease some economic activity between China and Russia, which has naturally contributed to diminished two-way commerce. Their curtailing of mutual tourism, trade, and transportation has amplified the effect of internal economic contractions. The Sino-Russian tourism industry essentially evaporated after the Russian government stopped issuing tourist visas to Chinese nationals (Moscow Times, April 24), which has deprived Russia’s hospitality industry of the main source of its foreign tourists. Though some corporate exchanges continued via video and other links, important joint infrastructure border projects, such as cross-river bridges, have been suspended.

The fragility of Russian-Chinese popular relations has also been evident in the crisis, despite years of targeted policies by both governments to promote binational social and cultural ties. As news of the virus outbreak in China emerged, Sinophobic sentiment rose in Russia: anti-Chinese racial and xenophobic comments appeared in Russian social media, while Russians surveyed in polls indicated they would avoid contact with Chinese-looking people (Ipsos MORI, February 14). PRC social media commentators complained about the harassment of PRC nationals in Russia and speculated that the Russian government was undercounting the spread of the infection within its territories (EurasiaNet, April 12).

When certain PRC tourists who were deported back to China for allegedly violating quarantine rules were found to be infected with COVID-19, some netizens speculated that Moscow was trying to export virus cases to China (NPR, April 10). Later, the Chinese government, while permitting commercial flights to continue, sealed off all land crossings to people along the Russian border (FMPRC, April 9). The decision came after travelers from Russia—predominantly Chinese nationals—became the largest source of imported COVID cases into China (CGTN, April 8). Frictions then arose about what to do with the large number of Chinese nationals stranded along the border in the Russian Far East, and Chinese social media commentators expressed fears that their compatriots were not receiving adequate protection against being infected (Global Times, April 9).

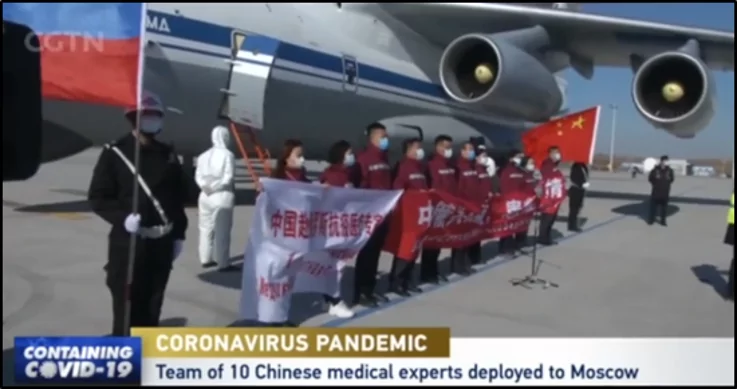

Notwithstanding these signs of popular dissatisfaction, neither government overtly criticized the other. Whereas the PRC attacked the United States for suspending travel and tourism with China, the government and media shrugged off Russia’s own severe travel restrictions and border closures. Afterwards, the Russian government reciprocated by not openly contesting China’s own subsequent severance of cross-border exchanges, which began in early April after many PRC nationals returning to China from Russia tested positive for the virus. The two governments also made a show of manifesting symbolic solidarity in combating the virus. In the first few months of 2020, Russia provided medical aid to China; in the following months, when the virus peaked in Russia, China delivered millions of masks and other items of protective equipment to Russia (Xinhua, April 11; TASS, April 4; CGTN, June 11). The Chinese media ran stories of Russian citizens thanking China for donating the medical supplies (Global Times, April 12).

Many of the Sino-Russian economic contractions are reversible. Taking advantage of the fall in world oil prices, China made large purchases of Russian oil in March, which resulted in a 17 percent growth in the value of Russian exports to the PRC in the first quarter of the year, and an overall 3.4% increase in two-way trade even as China’s commerce with Japan, the European Union, and the United States fell (SCMP, May 14; CGTN, June 11). As soon as the visa and border restrictions are relaxed, the number of tourists and other exchanges should also rebound. Noting that before the epidemic the flow of tourism was predominately that of Chinese citizens visiting Russia, Andrei Denisov, the Russian Ambassador to China, has indicated that his government foresaw more balanced tourist exchanges in the future (TASS, June 19).

Biotechnology and related ties will likely expand between the countries in the future, especially in the field of high-tech surveillance hardware and software. Scientists from Russia and China are working together to develop vaccines and other anti-viral medication. In a stroke of good timing, 2020 and 2021 have been designated “Years of Scientific and Technological Innovation in China and Russia” (China Daily, February 26).

Even more opportunely for Moscow, the Sino-U.S. confrontation over the pandemic came when it seemed that economic tensions between the two countries were de-escalating following their “Phase One” trade deal, which was announced with great fanfare at a White House ceremony on January 15. Nine days later, Russian presidential adviser Maxim Oreshkin called the deal “a big ticking time bomb” that would engender many global trade disputes (RT, January 24). Russian experts had feared that the deal would force Chinese importers to buy more U.S. goods at the expense of Russian products, but the COVID-19 crisis has upended the deal’s execution.

The pandemic may have decreased defense ties to a limited extent, since there have been no major joint exercises since the advent of the crisis. Furthermore, there may be delays in some areas of defense industrial cooperation that require cross-border travel, such as arms sales and professional military education exchanges. However, these changes will not fundamentally disrupt strong Sino-Russian security ties, even if they delay some activities. In fact, they may follow the U.S. example of employing fewer service personnel in the future and relying more heavily on computer-assisted command post exercises.

Throughout the crisis, the two governments have skillfully dampened potential sources of tensions. The Russian Embassy to China stressed that its border closure measures were temporary, while Chinese officials and media commentators have argued that Moscow’s actions were not motivated by malign intent, and were indeed understandable given the international situation. PRC media has also sympathetically noted the weaknesses of the Russian health sector, as well as the country’s “crucial period of domestic political adjustment”—a reference to Putin’s controversial proposal to revise the country’s constitution to allow him to remain in power after his second term (Global Times, February 19).

The Chinese Embassy in Russia initially lodged an official protest with the Moscow authorities regarding alleged racial and discriminatory harassment of Chinese nationals (Reuters, February 26). However, the Embassy quickly retracted the allegation after it became public, claiming that it had been a misunderstanding and that the Russian authorities were appropriately enforcing quarantine restrictions against all nationalities equally. The Embassy further urged Chinese citizens to follow all local regulations (SCMP, March 2).

Several months later, a Chinese editorial—one intended to urge Chinese nationals not to risk traveling back to the PRC, and thereby risk bringing more COVID-infected people into China—irritated the Russian government by describing its poor performance in containing the virus (Global Times, April 13). Russian Presidential Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov felt compelled to respond by declaring that the Russian government did not want to join in the exchanges of criticism among countries over the virus, and instead called on the international community to fight the virus (Izvestia, April 15). However, Peskov directed his criticism at the publisher of the editorial, The Global Times, rather than the Chinese government. Meanwhile, though PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian called on the Russian government “to provide convenience and guarantees for our citizens with regard to their stay and medical needs,” he directed all Chinese citizens to “comply with Russia’s pandemic prevention regulations” (FMPRC, April 9).

Russia and the PRC have also demonstrated a policy of eschewing open competition for influence in third countries. After a high-profile shipment of Chinese masks and aid to Serbia aroused some unease in Russia—whose leaders consider Serbia as falling within Moscow’s sphere of influence—China reduced its aid, while the Russian military intervened in force to assist the Serbian authorities in their response to the crisis (Eurasia Daily Monitor, April 14). In May, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov termed Western allegations—such as those made by U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper (Reuters, May 4)—that Chinese and Russian medical assistance to European countries was motivated by a desire to enhance their geopolitical influence as “another manifestation of Russophobia and Sinophobia” (Xinhua, May 15).

Presidents and Praise

The Xi-Putin high-profile partnership has continued despite COVID-19. As early as January 31, Putin sent Xi a telegram that “expressed confidence that the radical measures that the Chinese authorities were taking would help stop the spread of the epidemic and minimize the damage from it” (Kremlin, January 31). In several subsequent phone calls, the two presidents have pledged to cooperate against the virus, while praising each other’s performance. According to the PRC Foreign Ministry, in an April 16 conversation Xi said that “China will never forget Russia’s strong support during the gravest moment in its fight against the disease.” He also “expressed [China’s] confidence that under the strong leadership of President Putin, Russia will soon contain the spread of the virus to protect the safety and health of its people and bring economic and social development back on track” (PRC Foreign Ministry, April 17). Countering allegations of Russian mistreatment of Chinese nationals, Xi thanked Putin “for the active efforts Russia has made for Chinese nationals in Russia, saying he believes that Russia will, as always, protect Chinese nationals’ normal work and life on its soil” (Xinhua, April 17). According to the Kremlin’s summary of the same exchange, Putin praised “the consistent and effective actions of Russia’s Chinese partners, which helped stabilize the epidemiological situation in the country. He stressed that it was counterproductive to accuse China of releasing information to the global community on this dangerous infection in an untimely manner” (Kremlin, April 16).

Mutual exchanges of thanks were also evident in other official channels. In a lengthy March interview with the prominent Russian newspaper Izvestia, Beijing’s ambassador to Moscow, Zhang Hanhui, thanked Russia for rendering “sincere, timely, unwavering, and comprehensive” assistance to China in combating the virus. The Ambassador said the Chinese were “sympathetic” about the Russian restrictions on Chinese tourists entering Russian territory, and other epidemic control measures provided they were “moderate” and “consistent with the spirit of Sino-Russian friendship and the good level of bilateral interstate relations.” Zhang added that China was not preoccupied by the West’s “malicious attacks” and valued more the support of Russians and other “friendly nations” because these “true friends” constitute “the majority of voices of the international community” (Izvestia, March 16).

Likewise, the virus has given the Russian government another opportunity to ingratiate Moscow with the PRC leadership by defending China against the criticism of Western political leaders. On May 11, Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian singled out for praise how “President Putin and Foreign Minister Lavrov explicitly expressed objection to a handful of countries’ attempts to smear China and pin the blame on it with regard to COVID-19” (PRC Foreign Ministry, May 11). In his May 13 speech to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization [SCO], Lavrov denounced “baseless accusations against the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation” (TASS, May 13). Chinese and Russian diplomats affirmed solidarity within other multilateral institutions such as the United Nations and the BRICS [Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa] (TASS, April 28). Summing up their joint approach to the pandemic, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in his annual press conference during the third session of the 13th National People’s Congress on May 24 that “Together, China and Russia have forged an impregnable fortress against the ‘political virus’ and demonstrated the strength of the bilateral strategic coordination.” He further stated that the two countries will transform the current crisis into an opportunity to expand their future cooperation in many areas (CGTN, May 24).

Conclusion

The virus could have had a game-changing impact on the Sino-Russian relationship. Moscow has placed its bets on a growing Chinese economy serving as Russia’s main growth driver in coming years. The PRC’s mishandling of the initial virus outbreak, and the contraction of Sino-Russian trade, could plausibly have led Russian policy makers to reassess the wisdom of their intemperate alignment with China. However, China’s apparent rapid economic recovery, combined with Russia’s staggering economic problems–both those directly caused by the virus (e.g., domestic business closings), as well as second-order effects (e.g., collapsing demand for Russian hydrocarbon exports)—has for now convinced Russian policy makers that they need Chinese imports and investment more than ever (Carnegie.ru, April 27). Although the pandemic has set back the governments’ efforts to promote lagging societal ties, Xi likely echoed Putin’s sentiments that the two countries “should explore new flexible and diverse forms of cooperation amid regularized epidemic prevention and control measures so as to continuously push forward bilateral cooperation” despite the pandemic (Xinhua, April 17).

Richard Weitz, Ph.D., is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute in Washington, DC. The author would like to thank the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation for supporting his research and writing.