GEORGIA UNDER GROWING RUSSIAN PRESSURE AHEAD OF BUSH-PUTIN SUMMIT

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 2 Issue: 32

By:

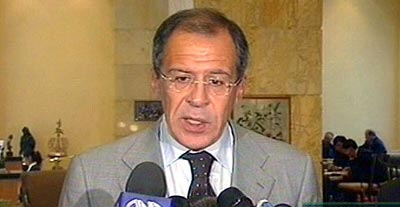

Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov’s imminent visit to Tbilisi appears designed for Washington’s consumption ahead of the George W. Bush-Vladimir Putin summit on February 24. Moscow wishes to avoid discussion of its ongoing threats to Georgia during the summit. Lavrov may briefly put on a display of benign intentions toward Georgia in order to keep the subject off the summit’s agenda. Such display might, perhaps, take the form of a South Ossetia settlement proposal, which must however be scrutinized for attempts to institute Russia as arbiter or guarantor of such a political settlement inside Georgia.

Lavrov’s decision to go ahead with the visit reflects Moscow’s awareness that Bush does have the necessary leverage to raise that issue prominently and effectively with Putin. Were the U.S. president led to conclude by Lavrov’s visit that the situation is on the mend, the threats to Georgia would soon resume with the ferocity of recent months, and may head for crisis in the spring with Russia’s military poised to strike at invented “terrorists” inside Georgia, having evicted the international monitors from the border.

Russian Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov voiced just that threat during the high-level NATO conference in Munich on February 13. He appeared emboldened by NATO’s tendency to put the best possible gloss on relations with Russia, even when the latter overtly threatens a NATO aspirant country and staunch U.S. ally in the midst of NATO’s highest conclave. With no evidence whatsoever, Ivanov accused Georgia of allowing “terrorists” to attack Russia from Georgian territory and reserved the right for Russia to carry out “preventive” strikes or attacks inside Georgia. He also accused Georgia of “trying to hasten the withdrawal of Russian bases” from the country [14 years into Georgia’s independence, Russia demands an 11-year extension on the bases.] Minister of Foreign Affairs Salome Zourabichvili replied, “Georgia is outraged by the accusations about terrorists and threats of preventive attack.” She also noted the contradiction between Moscow’s accusations and its simultaneous opposition to international monitoring of the Georgian side of the border. In response, Ivanov suddenly turned European fiscal advocate: “We don’t think that [monitoring] is a good use of European taxpayers’ money” (Itar-Tass, February 13).

By Moscow’s logic, if the OSCE’s Border Monitoring Operation (BMO) did not substantiate Russia’s accusations about terrorists, this does not mean that such accusations were wrong, but only that “the BMO was totally ineffective,” according to Ivanov. However, Russia now opposes international border monitoring as such, “near its border”; the more effective, the more objectionable to Russia — presumably because monitors might also see across the border into Russian territory, where local Chechens actually operate often undetected by Russian forces. Thus, “anti-terrorism” has become the pretext for evicting international observers from Georgia’s sovereign territory (easily misusing the OSCE for the eviction) and trying to set the stage for “preventive” strikes or operations inside Georgia in the spring, without inconvenient witnesses.

In Tbilisi, a Russian embassy statement ambiguously warned, “If there is specific information about a hotbed of terrorism posing a threat to Russia’s security, and if political, diplomatic, and economic methods have no effect, then the issue of some military steps will probably be seriously considered” (Rustavi-2 TV, February 14). Russia’s First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Valery Loshchinin, was somewhat more explicit: “Terrorists remain in Pankisi. It is necessary to broaden joint actions by our border guards, FSB, interior troops” (Vremya novosti, February 10). This seems to hint at Moscow’s earlier goal of moving its troops across the border into Georgia on a pretense of “joint anti-terrorist actions.”

Russia already has seized the Georgian side of the Georgia-Russia border in the Abkhaz and Ossetian sectors. On the excuse of “anti-terrorism,” it now seems to seek similar control of the Georgian side of the Chechen, and potentially Ingush and Dagestani, sectors. The OSCE at the moment is completing the evacuation of the BMO from the Dagestani sector, where Moscow says “terrorists” can cross. Meanwhile, on February 12, the Russian-installed new leadership of Abkhazia was inaugurated.

In the February 10-11 negotiations on military issues in Tbilisi, the Russian side piled up new preconditions, amounting in practice to an outright refusal to withdraw its troops based in Georgia (see EDM, February 14). In the wake of that round, a Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs communique reaffirmed the long-obvious reality that Russia is not bound by the 1999 Istanbul Commitments on troop-withdrawal (Interfax, February 14). Although some of the points in this Russian argument can be proven wrong, it is a fact that the Istanbul Commitments are nonbinding, are phrased in a way that leaves their implementation in Georgia at Russian discretion, do not even specify the goal of troop withdrawal, and do not entail a timeline for implementation. (There was a 2001 timeline for agreeing to start implementation, but Russia broke the deadline, and the OSCE hastened in 2002 to give up any deadline.) Moscow’s communique shows yet again that the Istanbul Commitments are a weak and increasingly irrelevant basis on which to call for withdrawal of Russian troops from Georgia (and from Moldova as well). To cling to this straw is to advertise confusion, indecision, and the absence of a real policy, all of which encourages Russia to dig in its military heels. As Giorgi Bokeria concluded after this negotiating round, Georgia can make a far stronger legal case based on national sovereignty and international law.

Those concerted military and political pressures are Moscow’s response to Georgia’s constant overtures and economic open door toward Russia. In his February 10 interview, Loshchinin acknowledged, “Our economic relations with Georgia have grown deeper with the advent of the new leadership. Russia’s economic presence in Georgia is now weightier than ever before; our capital is entering all the major economic sectors.” That same day, in a state-of-the-nation address to parliament, President Mikheil Saakashvili stated, “I am ready to go again to Moscow, ready to meet again with President Putin and extend to him my hand of friendship, which has been outstretched in the air since we met almost a year ago” (Rustavi-2 TV, February 10).

Clearly, however, Moscow seeks long-term domination rather than the good-neighborly relations and cooperation that are on offer from Tbilisi. For the moment, it also tries to reassure Washington in the run-up to the summit that the situation is improving, only to step up the pressures shortly afterward, unless Bush raises the issue with Putin in Bratislava.