Georgia’s Anaklia Deep-Water Port Faces a New Challenge

Georgia’s Anaklia Deep-Water Port Faces a New Challenge

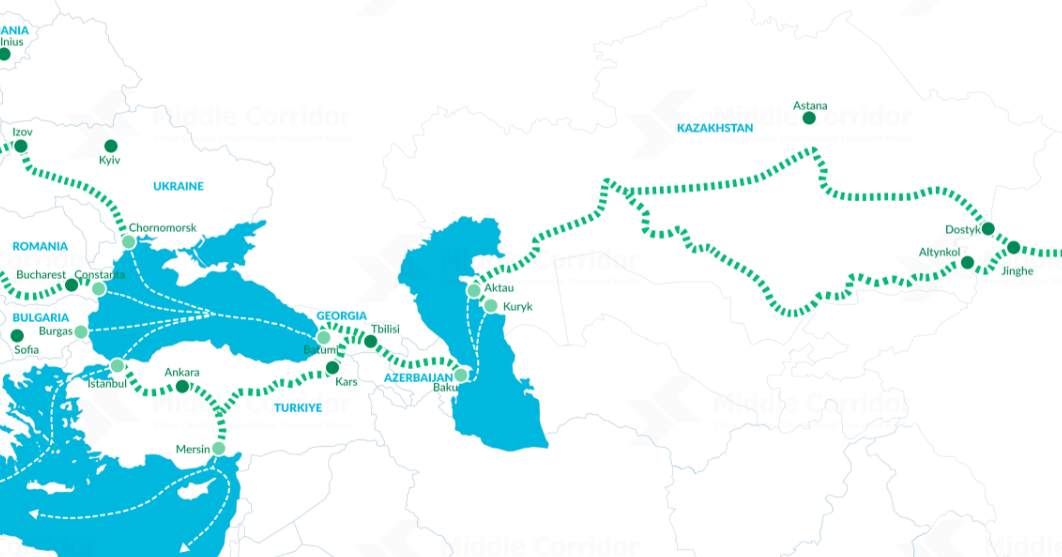

Recent developments around the construction of a new deep-water port in Anaklia, on Georgia’s Black Sea coast, have reinforced skepticism that the “project of the century” (as it has come to be known domestically) will ever be able to attract sufficient foreign investment and become a hub for goods being shipped between China and Europe (see EDM, May 20).

Specifically, on June 3, the Anaklia Development Consortium (ADC) protested against the decision of the Georgian Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development to issue a new deep-watering, multi-purpose construction permit to the JSC Corporation, which is developing the nearby Poti Sea Port (Portseurope.com, June 3). Located only 35 kilometers south from Anaklia, Poti is currently the largest seaport in Georgia, able to handle 6–6.5 million tons of cargo per year. It presently deals with 85 percent of the country’s container traffic. In April 2011, APM Terminals purchased the Poti port facilities and announced plans to build new, deep-sea “mega-port” there (Apmterminalspoti.com, accessed June 18).

Oddly, the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development issued the building permits for the Poti mega-port precisely as negotiations between the Georgian government, the Anaklia Development Consortium and foreign investors were finally coming to a close (Oc-media, May 30). ADC suspects that the ministry’s decision deliberately puts the consortium in a difficult position with investors. In a June 3 statement, the Anaklia port consortium described the news as “shocking” and said that the government threatens the deep-water port project, possibly leading to its suspension (Portseurope.com, June 3).

Georgian Economy Minister Natia Turnava replied that she did not know such a permit had ever been issued. She blamed the head of one of her ministry’s agencies, Grigol Kakauridze. Turnava told reporters that Kakauridze had been dismissed from his post. Later, Kakauridze confirmed that the minister did not know about his decision to allow the construction of an alternative deep-water port at Anaklia (Commersant.ge, May 31)

The vice president of the Atlantic Council of Georgia and a fellow at the McCain Institute for International Leadership, Batu Kutelia, asserted on June 10, in an interview with this author, that the confusion around the Anaklia project, which is strategically important for Georgia, confirms not only the incompetence of the authorities, but also the propensity of government officials to act against the interests of their country. “By looking at the situation through a criminal investigative lens and posing the question ‘Who benefitted?’ it becomes clear that Russian interests were strategically served.” Specifically, he explained, “The incident with the Poti port diminished the possibility of building a deep-sea port in Georgia in either of the proposed locations—Poti or Anaklia.” Kutelia continued, “The next question is ‘How did it happen?’ [And the answer is that] it is the result of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s [the head of the ruling Georgian Dream party] informal, deinstitutionalized governance system, where formal officials like the prime minister or government ministers are nominal [façade] individuals serving the interests of Ivanishvili and various powerful business groups involved,” the expert underlined.

According to Kutelia, “Many players in this [governance] system are directly or indirectly linked to external players with dubious interests; but additionally, the entire system of informal governance is heavily infiltrated and manipulated by Russian special services.” He contended that, “the absence of a US ambassador in Georgia and only light warnings from some of the European envoys [in Tbilisi], it makes it difficult to halt the further deterioration of this process” (Author’s interview, June 10).

Georgian opposition politicians believe that the scandal around the port of Anaklia highlights the oligarchic nature of power in the country as well as the influence of large business groups on major government decisions. One of the leaders of the European Georgia party, David Darchiashvili, told this author that APM Terminals (Poti Sea Port) is most often associated with the banker Vano Chkhartishvili, who is close to the billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili. The European Georgia party leader also confirmed that, according to his information, members of Chkhartishvili’s family “have an interest in the port of Poti.” Darchiashvili added, “Potential investors in Anaklia doubted how expedient and profitable it would be to invest hundreds of millions of dollars into the deep-water port construction project. They demanded state guarantees and suddenly found out that the government allowed the construction of an alternative port in Poti that could become a competitor” (Author’s interview, June 9).

Darchiashvili expressed hope that a future investigation might determine which factors played a decisive role in the sabotage of the Anaklia project: illegal lobbying of oligarchic groups or a secret intervention by Russia, which is not happy about the perspective of a huge transport hub being built on Georgia’s Black Sea coast (Author’s interview, June 9).

The paradox of the situation around the “project of the century” is that Georgian Prime Minister Mamuka Bakhtadze as well as leaders of Georgian Dream have repeatedly expressed full support for Anaklia and a readiness to allocate significant sums from the state budget for the success of the entire project.

Georgian Dream member of parliament Zakaria Kutsnashvili claimed that “two deep-water ports are better than one” because they will compete and such competition “has a positive effect on the market.” Yet, he conceded, “in our reality, it is better to give priority to the port of Anaklia—complete its construction and only then begin work on the expansion of the port of Poti” (Author’s interview, June 9).

Considering the many economic and political difficulties and challenges the Anaklia seaport project continues to face, support from the West—particularly from Europe—may prove decisive for its success. But the intensity of this support will depend on how crucial a new Black Sea deep-water port may prove for the transit of goods between Asia and Southeastern Europe.