Growing PLA Transparency as a Means of Employing Soft Power, Part 1: PLA Internal Signaling Since the 18th Party Congress

Growing PLA Transparency as a Means of Employing Soft Power, Part 1: PLA Internal Signaling Since the 18th Party Congress

As China emerges during the 21st Century as a strong regional power with a growing global footprint, the role of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as a means of employing “military soft power” (军事软实力) has garnered close scrutiny both internally and externally from multiple perspectives, including the development and deployment of advanced weapons and equipment, as well as being involved in an increasing number and scope of domestic and international training exercises and drills. This article, the first of a two-part series, examines the PLA’s use of soft power for both internal and external signaling.

It appears that China did not formally apply the concept of “military soft power” to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) until Hu Jintao took over the leadership in September 2004. [1] Under Hu and Xi Jinping, who took over power in 2012, one of the key aspects of soft power has been the increasing level of military transparency (透明) concerning not only interaction with foreign militaries but also internal PLA issues.

Disagreements on the issue of transparency have always been at the core of China’s foreign military relations. For example, the U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report to Congress on the Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2014 stated:

Although the dialogue between the United States and China is improving, outstanding questions remain about the rate of growth in China’s military expenditures due to the lack of transparency regarding China’s intentions.

It is difficult to estimate actual PLA military expenses due to China’s poor accounting transparency and incomplete transition from a command economy. China’s published military budget omits several major categories of expenditure, such as procurement of foreign weapons and equipment.

China’s lack of transparency surrounding its growing military capabilities and strategic decision-making has led to increased concerns in the region about China’s intentions. Absent greater transparency from China and a change in its behavior, these concerns will likely intensify as the PLA’s military modernization program progresses. [2]

In September 2014, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Russell, the senior U.S. diplomat for East Asia, stated, “Frankly, the lack of transparency in China’s military modernization is the source of some concern to its neighbors. And we believe that all of the region, including China, would benefit from increased transparency” (Reuters, September 13, 2014).

Although the PLA’s last two biennial Defense White Papers did not specifically address the issue of transparency, a commentary in China Military Online on the publication of the 2012 Defense White Paper by Rear Admiral Guan Youfei, director of MND’s Foreign Affairs Office stated:

“It should be said that the transparency of the PLA is consistent with the reality of our national and military situation. Military transparency is important for national security. The extent, method, content and timing of transparency to the outside world should be determined according to each country’s safety situation and no country is absolutely transparent when it comes to military affairs. In recent years, the Chinese military has adopted a series of measures to open itself to the world, such as establishing a news spokesperson system for MND, opening a website of MND (https://eng.mod.gov.cn), and inviting foreign correspondents to visit and interview, all of which were unimaginable ten years ago. It could be said that China is very transparent on military affairs” (China Military Online, April 17, 2013).

Opening of the PLA to the Public

In order to address foreign concerns about transparency, the PLA has implemented several administrative and organizational solutions since the mid-2000s. Specifically, the PLA has gradually expanded the content of its eleven biennial Defense White Papers that was first published in 1998, established the Ministry of National Defense (MND) Information Office in September 2007, and created a new MND website, with both English and Chinese versions, that came online on August 20, 2009 (China Daily, July 23, 2009). In 2007, MND began holding ad hoc press conferences, which became monthly in 2012. [5] In August 2009, MND created official websites in Chinese (www.mod.gov/cn) and English (https://eng.mod.gov.cn/), which is also known as “China Military Online” or chinamil.com. In addition, the PLA created separate Chinese websites for the General Logistics Department (GLD), General Armament Department (GAD), Navy (PLAN), Air Force (PLAAF), Second Artillery Force (PLASAF), and all seven military regions (MR), each of which used 81.cn (e.g., August 1st or bayi) as the base. [6] In addition, the PLAN, PLAAF, PLASAF, and MR newspapers, each of which were previously for internal use (内部) or military use (军内) only, removed those restrictions and became available publicly through a post office subscription. However, major changes occurred to several of the newspapers in January 2016 as a result of the PLA reorganization. Specifically, the individual MR newspapers ceased publication that month, and, similarly, the GLD, GAD, and MR websites also disappeared and have been replaced by a new general website (军报记者 / https://jz.81.cn) and separate websites for the new Logistics Support Department, Equipment Development Department, Army Headquarters, and each of the theater commands (hq.81.cn/; zf.81.cn/; https://army.81.cn/ ;db.81.cn; nb.81.cn; xb.81.cn; bb.81.cn, and zb.81.cn;). In addition, a second military website for video (中国军视网 / https://tv.81.cn/) was also created on December 29, 2015. In addition, China Central Television (CCTV) has greatly increased its coverage of PLA activities.

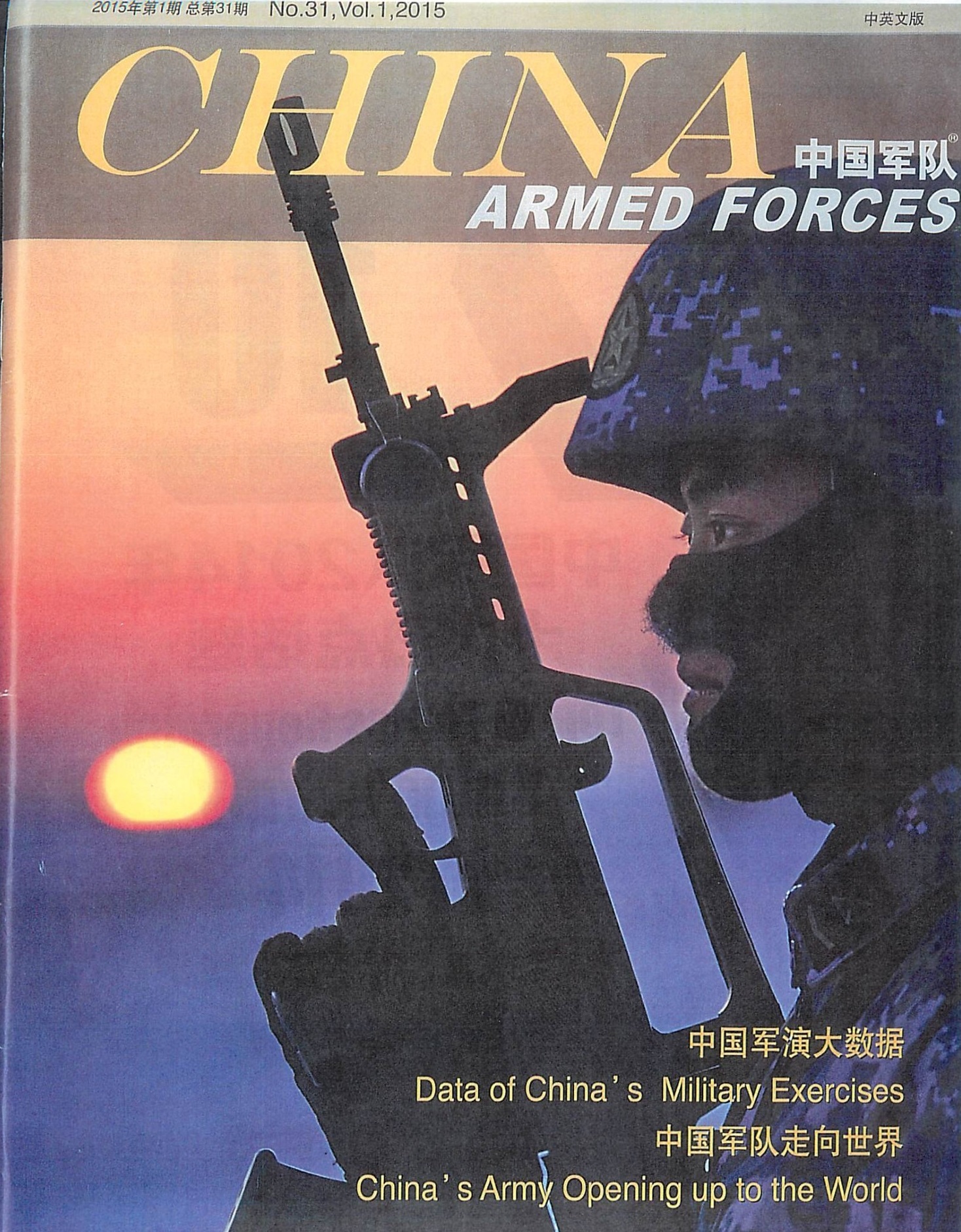

In 2009, the PLA component of Xinhua began publishing a new 110-page quarterly journal in Chinese and English entitled China Armed Forces (中国军队). Since January 2012, it has been published bimonthly. Certain volumes have focused on specific topics, such as the military service system and various anniversaries, including the founding of the PLA (1927), PLAN (1949), PLAAF (1949), and the end of World War II (1945). Starting in 2013, the first issue for each year has had lengthy articles that review key PLA activities for the previous year, including military relations, joint and combined exercises, peacekeeping operations, and military operations other than war (MOOTW) activities, as well as some important policy and weapons issues. The same information is also available on various Chinese websites.

Key PLA Issues for 2013 through 2015

Although the PLA has clearly expanded the release of its overall information over the past several years, the remainder of this article focuses on information that the PLA published at the end of 2013 through 2015 that it identified as its top issues during the previous year.

The primary sources for this information is China Armed Forces magazine and various military news outlets. Specifically, the first issue of China Armed Forces magazine in 2014 carried two lead articles entitled “Highlights of China’s Military Diplomacy in 2013” that identified the top nine military relations events and “Military News in 2013” that is a mix of policy, weapons, and military relations. [7] This was the first time since the magazine was created in 2009 that it listed these accomplishments, which indicates that military diplomacy has become a more important and transparent element of the PLA.

On December 26 and 29, 2014, MND’s official website published “Ten Breakthroughs of China’s Military Diplomacy in 2014,” which were also published in the first volume of China Armed Forces in 2015. [8] According to the article, “In 2014, the Chinese military played a more active role in assuming the responsibilities of a major country, deepened its relations with the militaries of many countries, aired its voices more loudly, and carried out military drills in a more practical way. If we have to summarize China’s military diplomacy in 2014 with one sentence, the best choice may be ‘military shows more major-country style’.”

On December 30, 2015, the newly created China Military Network published an article that identified the top ten military activities during 2015 (China Military Online, December 30, 2015). A list of 39 key activities were identified which can be organized into the following seven categories, some of which clearly overlap:

1. Combined Training, Meetings, and Agreements with Foreign Militaries

2. Joint and Combined-arms PLA Exercises and Training

3. PLA Navy Activities

4. PLA Air Force Activities in the East China Sea ADIZ

5. UN Peacekeeping

6. Army Building and Discipline

7. Defense Industry and Equipment.

The following sections address the latter two categories, which are focused on domestic military affairs.

Army Building and Discipline

One of the most prolific themes has dealt with what the PLA calls “army building” (军队建设), which includes everything from acquiring weapons and equipment to developing doctrine and dealing with personnel and organizational issues, especially problems with corruption. Because this is an area that the central leadership is eager to spread information about—and enforce its directives—there is a higher degree of transparency and greater media attention given to it. The following bullets lay out the top ten issues involving army building the PLA identified for 2013 through 2015.

1. Xi Jinping sets new goals for army building during the First Plenum of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) in March 2013, where he urged the armed forces to be “absolutely loyal” to the Party, to sharpen their fighting capabilities, and abide by discipline in order to elevate the country’s defense and army building. [9]

2. During the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress in November 2013, “The Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms by the Party Central Committee,” which focused on developing theories and strategic guidance, reforming the organizational structure, and deepening military-civil fusion.

3. In April 2013, the eighth biennial Defense White Paper provided true unit designators for all 18 group armies for the first time.

4. In 2013, the PLA adopted a series of measures to strengthen management, that focused on managing expenses related to corruption, including confiscating 23,231 illegal homes and reducing the number of official cars by 25,510.

5. During 2014, Xi led a campaign to root out corruption in the PLA, which included a meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Politburo in June.

6. In October 2014, Xi led a meeting in Gutian, Fujian Province, to commemorate the 85th anniversary of the first Gutian Meeting. The meeting focused on the Party’s absolute leadership over the PLA and the goal of eliminating corruption in the PLA.

7. From November 24–26 2015, Xi chaired a CMC meeting concerning the PLA’s reorganization (军队改革), which was then implemented.

8. During 2015, the military and PAP implemented the “Three Stricts and Three Honests” (三严三实), which is an internal education campaign led by the CCP aimed at improving the ethical conduct of Party officials and “improving political ecology” (China.org, June 15, 2015).

9. On September 3, 2015, Xi announced that the military would implement a 300,000-man force reduction, which is the eleventh force reduction and reorganization since 1952.

10. On May 26, 2015, China issued its ninth biennial Defense White Paper, which focused on military strategy.

Defense Industry and Equipment

Although the acquisition of PLA weapons and equipment is one of the black holes in China’s military transparency, the PLA identified three key issues during 2013 to 2015, most of which, ironically, was based on foreign reporting. By using foreign media reports, Chinese state media is able to discuss what would otherwise be sensitive information, and frame the development of Chinese military capabilities in a way that is palatable to the state.

1. During 2013, China’s defense industry in conjunction with the PLA displayed and deployed several new types of equipment and weapon systems, including showing the Y-20 and deploying new types of destroyers, as well as command and escort vehicles.

2. During 2014, the PLAN was scheduled to commission several vessels from China’s shipbuilding industry, including a Type 052D destroyer and Type 056 corvette. Supposedly, dozens of Type 056 corvettes are under construction in five shipyards.

3. During 2014, China and Russia signed several military trade deals, including contracts involving fighters and air defense missiles, as well as bilateral cooperation on large aircraft, highly sensitive and advanced navigation satellites, and nuclear energy.

Conclusion

Most foreign news articles tend to focus on the PLA’s growing arsenal of weapons and China’s “aggressive behavior” in the East China Sea and South China Sea, as well as its growing diplomatic, economic, and military relations around the world. [11] The information identified by the PLA in this article has clearly helped shape the view of the PLA from a military soft power perspective, and forms an important part of its domestic propaganda mechanism, by being transparent on issues about which it wants to increase social attention to, such as “military building” and framing information about its developing military capabilities through the use of foreign media attention.

Part two will examine the impact of Joint and combined-arms PLA exercises and training on transparency and soft power.

Kenneth W. Allen is a Senior China Analyst at Defense Group Inc. (DGI). He is a retired U.S. Air Force officer, whose extensive service abroad includes a tour in China as the Assistant Air Attaché. He has written numerous articles on Chinese military affairs. A Chinese linguist, he holds an M.A. in international relations from Boston University.

Notes

- Kenneth Allen, Trends in People’s Liberation Army International Initiatives under Hu Jintao, in Roy Kamphausen, David Lai, and Travis Tanner, eds., Assessing the People’s Liberation Army in the Hu Jintao Era, United States Army War College Press, April 2014.

- Annual Report to Congress on the Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2014, U.S. Department of Defense, April 24, 2014, found at https://www.defense.gov/pubs/2014_DoD_China_Report.pdf.

- Xiao Jingmin, “A Theoretical Exploration into the Soft Power in China’s National Defense,” and “The Ministry of National Defense (MND) will launch an official bilingual website on August 1,” https://china-defense.blogspot.com/2009/07/ministry-of-national-defense-mnd-will.html. The literal translation for the Information Office is the News Service Bureau and it is just one of several MND bureaus.

- Information on the monthly conferences, which are usually held on the last Thursday of the month, is based on a review of the MND website’s press briefings tab, found at https://eng.mod.gov.cn/Press/index_3.htm.

- The websites, some of which no longer exist, are as follows: GLD (zh.81.cn), GAD (zz.81.cn), PLAN (navy.81.cn), PLAAF (kj.81.cn), PLASAF (ep.81.cn), Shenyang MR (sy.81.cn), Beijing MR (bj.81.cn), Lanzhou MR (lz.81.cn), Jinan MR (jn.81.cn), Nanjing MR (nj.81.cn), Guangzhou MR (gz.81.cn), and Chengdu MR (cd.81.cn).

- Luo Zheng, “Highlights of China’s Military Diplomacy in 2013” (2013 中国军队走处国门亮点频现), China Armed Forces, No 25, Vol.1, 2014, pp. 16–19. Editorial Department, “Military News in 2013” (2013年中国十大军事新闻), No 25, Vol. 1, 2014, pp. 13–15.

- Yao Jianing, ed., “Ten breakthroughs of China’s military diplomacy in 2014” parts 1 and 2, China Military Online, December 26 and 29, 2014, respectively, found at https://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/2014-12/26/content_6286046.htm and https://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/2014-12/29/content_6288402.htm. The Chinese article, which included all ten events was found at https://www.81.cn/jmywyl/2014-12/25/content_6284840.htm. The article noted that the ten breakthroughs are listed in chronological order not by precedence. Kong Xianglong, “Top 10 Topics Regarding China’s Army in 2014” (中国军队2014年十大热点话题), China Armed Forces, No. 31, Vol. 1, 2015, pp. 6–11.

- Zeng Xingjian and Hong Yihu, “Passing the Strait of Magellan,” China Armed Forces, No. 24, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 80–83. Official Chinese English-language publications, such as the biennial Defense White Paper, refer to the South Sea Fleet as the Nanhai Fleet.

- Note: China’s “armed forces” (武装力量) is composed of three components: 1) the PLA, 2) the People’s Armed Police (PAP), and 3) reserves and militia. It is often just referred to as the “military” (军队).