Hobson’s Choice: China’s Second Worst Option on Iran

Publication: China Brief Volume: 10 Issue: 6

By:

In late February, a high-level Israeli delegation visited China in an attempt to convince Beijing to go along with sanctions against Iran. Headed by Lieutenant General (ret.) Moshe Ya’alon, vice prime minister and minister for strategic affairs and former chief of general staff of Israel’s armed forces; Professor Stanley Fischer, governor of the Bank of Israel; and Ms. Ruth Kahanoff, deputy director general for Asian and the Pacific of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the delegation reportedly provided the Chinese with the most detailed intelligence information in over three years on the military aspects of Iran’s nuclear program. It also offered solutions to China’s so-called "dependence" on Iran’s oil, to be discussed below (Ha’aretz, March 1).

Although the Chinese appreciated the Israeli "pilgrimage," the visit has apparently failed—not because the delegation botched convincing Beijing but because Beijing had probably made up its mind about Iran long before. China did not need the Israeli delegation to expose Iran’s military nuclear program. Except for Russia, China has a long-standing presence in Iran—more than all other permanent members of the UN Security Council—and therefore must be well aware of Iran’s plans. Still, the Chinese officially insist on a diplomatic settlement of the conflict, leaving the harsh words to its pseudo-governmental think tank academics who occasionally twist the truth. For example, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) Professor Ye Hailin, who said, "Actually, China has never imposed sanctions on any country in history," was perhaps right in the narrow sense of terminology (China Daily, February 23). Yet, Beijing’s absence or abstention in a number of UN Security Council votes has facilitated the imposition of sanctions on other countries, Iran included. For example, on July 31, 2006, the PRC voted for UN Security Council Resolution 1696, calling on Tehran to suspend "all [nuclear] enrichment-related and reprocessing activities, including research and development" by August 31, 2006—"or face the possibility of economic and diplomatic sanctions."

Washington’s recent announcement of its intention to sell arms to Taiwan has led the international media to conclude that the chances of Beijing joining a sanction regime against Iran have now diminished substantially. This virtual link between Taiwan and Iran is not new. Unable to respond directly to U.S. military and other gestures toward Taiwan, the Chinese have often made use of Iran as a proxy not only to indicate their dissatisfaction and irritation but also to retaliate against Washington by making their own military and other gestures to Iran. Apparently, the announcement of the long awaited Taiwan arms deal aborted U.S. Secretary of State Hilary Clinton’s attempts to enlist China’s implicit, if not explicit, acceptance of sanctions against Iran. This conclusion, that the Chinese are determined to block sanctions against Iran, should, however, be recalibrated.

As the showdown on Iran’s sanctions approaches, Beijing is gradually moving into the focus of international attention as, allegedly, the main obstacle on the way of stopping Iran’s race toward nuclear weapons. Some attribute it to an initial change in the Chinese behavior in the direction of greater global activism, including a more assertive policy on defending Iran and blocking the proposed sanctions, reflecting China’s emergence as a great and arrogant power. Given the growing Sino-U.S. friction—related not only to Taiwan but also to the increased intimidation of American companies in China, the Google imbroglio, the recent Dalai Lama’s meeting with President Obama and China’s reported cyber intrusions—greater Chinese intransigence, also on Iran’s nuclear issues, is almost expected, yet not automatically.

Over the years, the media has reiterated that China would block sanctions against Iran because, among other things, Iran is one of China’s major oil suppliers. Actually, over the last year Chinese oil imports from Iran have steadily declined (perhaps in anticipation of sanctions) and, not less important, Saudi Arabia had already promised Beijing to supply whatever amounts of oil it needs in case Iranian oil would stop flowing (See "The Strategic Considerations of the Sino-Saudi Oil Deal," China Brief, February 15, 2006). Saudi Arabia is now China’s leading oil supplier. Iran’s share in China’s oil import, that nearly peaked at 16.3-16.4 percent in January-February 2009, consistently shrank to 11.8 in March, 10.6 in August, 8.5 in October, 6.9 in December, falling to 6.3 percent in January 2010. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia’s share, that at times was lower than Iran’s, has begun to pick up reaching over 27 percent (in September 2008 and February 2009), 24 (in July 2009), and over 23 percent (in November-December 2009)—more than three times over Iran. In 2009, China surpassed the United States as Saudi Arabia’s top oil importer and as ARAMCO (Saudi Arabian Oil Corporation), the world’s biggest crude oil producer, top customer (China Daily, February 1). China’s oil import from Saudi Arabia in 2009 stood at 41,857,127 tons, approximately 81 percent more than oil imports from Iran that reached 23,147,244 tons (all oil information calculated from chinaoilweb.com).

This steady change may indicate that Beijing is gradually and slowly shifting some of its Iran oil import sources to other suppliers—primarily, but not only, Saudi Arabia—in possible anticipation of forthcoming sanctions or even a military offensive. While Iran remains one of China’s major oil suppliers, it is by no means indispensable. In case of a diplomatic dead end, the Chinese have apparently arranged for alternative oil suppliers, preparing in advance for a worse scenario, namely sanctions. Still, these preparations could be disrupted if sanctions fail to be approved or implemented, which could possibly lead to a war that is likely to block all oil supplies from the Persian Gulf. This is the worst scenario that Beijing would have to face.

While China has acquired substantial investment assets in Iran, much of it is in future commitments. The share of Iran in China’s foreign economic cooperation turnover in 2007 was around 2.4 percent and far from the top of the list. It was preceded by at least a dozen countries whose economic cooperation with Beijing was greater, Saudi Arabia included. Notwithstanding its image, Iran also lags far behind as China’s foreign trade partner compared with other countries. Its share in China’s imports (oil included) was less than 1.4 percent in 2007 and in China’s exports, a little over 0.5 percent; a total of less than 1 percent (China Statistical Yearbook 2008). Put differently, if worse comes to worst, the temporary loss of Iran both as a market for export and investment, and even as a source of oil, could be harmful and painful for Beijing, but not disastrous or fatal. However economically and strategically important, Iran is not, and has never been, vital for China.

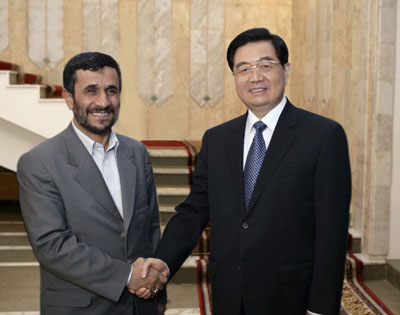

To be sure, Beijing has never been terribly enthusiastic about Tehran. In addition to their misgivings about the personality and leadership of Mahmud Ahmadinejad (expressed privately but never in public), China’s leaders have been suspicious about Iran as a source of Islamic radicalism, terrorism and regional instability which are detrimental to China’s foreign policy and economic interests (Lecture By Prof. Li Shaoxian, Vice President, China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, Jerusalem, February 21, 2006). Beijing must be upset, and probably reprimanded Tehran (in private), for transferring Chinese-made or Chinese-designed weapons to other customers (such as Hamas and Hizbullah), thereby violating earlier arms sale agreements about end-users in an attempt to drive a wedge between China and Israel, undermine their relations and embroil them in a skirmish ("Silent Partner: China and the Lebanon Crisis," China Brief, August 16, 2006). Beijing has also criticized Ahmadinejad’s denial of the holocaust (some of whose survivors found a safe haven in China) and his reiterated threats to destroy Israel. Together with some other members, Beijing is still blocking Iran’s admission as a full member to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and by no means welcomes Iran’s nuclear weapons. "The potential ‘Persian bomb’ worries not only Israel, the United States and Europe, but also Arab countries and even remote China….No matter how the Iranian nuclear crisis develops, a Persian bomb must not come into existence" [1].

As the Chinese leadership drags its feet slowly to the decision-making junction on Iran, it appears to have little choice. Although the media points to the possibility that China would veto any UN Security Council resolution to impose sanctions or use force against Iran, this is highly unlikely. So far, Beijing has been very stingy in using its veto. From its admission to the UN in October 1971, to the end of 2008, China cast its veto only six times, the lowest among UN Security Council members (out of 261 times that veto was cast: USSR/Russia: 124; United States: 82; United Kingdom: 32; and France: 18). In using their veto power, the Chinese blocked resolutions of marginal international significance (related to Bangladesh, Guatemala, Zimbabwe, Myanmar and Macedonia) and consistently avoided blocking resolutions of profound global impact (Global Policy Forum). It is likely that Beijing would veto resolutions that affect its national security, territorial integrity and its strategic belt (North Korea, Pakistan, Taiwan). Iran does not fall in this category and is by no means part of these Chinese concerns. It is doubtful that Beijing would use its veto for Tehran’s sake (The London Times, February 10).

If the Chinese decide to use their veto to block a resolution on sanctions, they have to consider the implications. To be effective, sanctions—whatever their contents—have to be applied universally. Otherwise, the target of sanctions would continue to receive whatever it needs from other sources. In fact, in late September 2009, media reports said that Chinese refineries and companies have been supplying Iran with gasoline (whose domestic demand cannot be met by Iranian refineries) for at least a year. This must have been done indirectly through intermediaries, since such exports do not appear in Chinese statistics. The Chinese share in Iran’s gasoline imports is said to reach one third (AFP, September 22, 2009; Tehran Times, September 24, 2009; Al-Jazeera, September 23, 2009). Chinese export statistics to Iran do mention over 4,700 tons of Kerosene, 3,600 tons of Jet Kerosene, 1,700 tons of Fuel Oil and 360 tons of Diesel Oil, in 2009 alone (data from chinaoilweb.com). This is just one example of why China needs to participate in, and contribute to, the contemplated "sanctions regime" against Iran. If Beijing undermines this regime either by the use of its veto or by circumventing an imposed embargo on Iran, it might, unintentionally, pave the ground for the next step that could be—as the Israeli delegation may have implied—the use of force. Apparently, both China and Israel are concerned about it. On March 16 PRC ambassador in Israel Zhao Jun told the Israeli vice-foreign minister in unequivocal terms that China is opposed to a nuclear Iran. The next day, as China’s vice-premier Hui Liangyu left for Israel, it was reported that Prime-Minister Netanyahu and Foreign Minister Liberman will visit China (Israel Today, March 17).

For years, the Chinese have used a variety of tactics to postpone resolution of the Iran nuclear ambitions and suffocate international attempts to force Tehran to abandon its nuclear program. Now, Beijing perhaps realizes that blocking sanctions could entail a war against Iran, an option that—from its own standpoint and that of the international community (including Iran)—is far worse. It is inconceivable that Beijing would vote for comprehensive sanctions (China Daily, March 8)—though since 2006 it voted at least five times for sanctions, only after it was significantly pared down in scope, against Iran. However, it could enable solid sanctions against Iran by abstaining, a routine and common feature of Chinese foreign policy. The precedent of China’s abstention that had enabled the UN Security Council to launch a military offensive against Iraq in the First Gulf War comes to mind. Unlike sanctions, the use of force does not have to reflect universality or unanimity to be effective, as demonstrated in the Second Gulf War. If sanctions are not imposed, or fail, armed offensive could be launched by one, or some, of the governments opposed to Iran’s nuclear threat. For Beijing (and Tehran), war is the worst scenario. Sanctions are the second worst as they still provide a window of opportunity and give time for further negotiations and diplomatic efforts—Beijing’s preferred way to settle regional and international conflicts, including the Iranian issue. Beijing would not like to be held responsible for using force against Iran.

Tehran is probably well aware of Beijing’s predicament and foreign policy priorities. Iranian opposition parties and publications, as well as research institutes have for some years warned the government that ultimately, China would prefer its relations with the United States and should not be counted on. An Iranian editorial noted, for example, that China (and Russia) should not be fully trusted as they "adopt positions on the basis of their interests, calculations and considerations, and pinning our hopes on a division of East and West is not an entirely secure bet in safeguarding our national interests" [2]. Washington must also be aware of China’s predicament and foreign policy priorities. In fact, Beijing’s agreement to abstain on the resolution to use force against Iraq in 1990-1991 had been an outcome of bargaining: Washington agreed to resume economic and political (though not military) relations with Beijing, suspended after the Tiananmen massacre. Twenty years later, a Chinese abstention is again needed by the United States in order to push forward a resolution to impose sanctions on Iran. To be sure, Washington prefers milder sanctions against Iran with China than tougher sanctions without China.

In sum, the assumption that China would stand by Iran because of its "dependence" on Iran’s oil is shaky, not only because the Chinese—based on long-term planning—have been smart enough to cultivate alternative suppliers, but also because Tehran has become dependent on China. In fact, one of the interesting and less studied elements of China’s foreign policy since the mid-1990s has been the Chinese creation of "counter-dependencies." To offset excessive dependence on other countries, first and foremost suppliers of energy and raw materials as well as technology, Beijing has been offering generous aid programs, transferring arms, investing in infrastructure and long-run projects, and expanding export. Consequently, China is not as dependent on Sudan or Iran as Sudan and Iran are on China. This gives the Chinese greater room for maneuver and flexibility toward such countries than is usually assumed. Compelled to make a choice between sanctions and war, Beijing may ultimately prefer the former to the latter, something it has done before.

Notes

1. Prof. Yin Gang (CASS), "China Has No Sympathy for a Persian Atomic Bomb," Daily Star, Beirut, February 7, 2006.

2. Editorial, "Observations on the Anti-Iranian Resolutions," Jomhuri-ye Eslami [Islamic Republic], Tehran, October 7, 2008. An April 2006 Majlis [Parliament] Research Center report said that China does not prefer Iran to the United States and that Beijing’s cooperation with Tehran would not cross a point that would displease the United States.