Hollow Words and Apparent Setbacks at the Russia-Africa Summit

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 122

By:

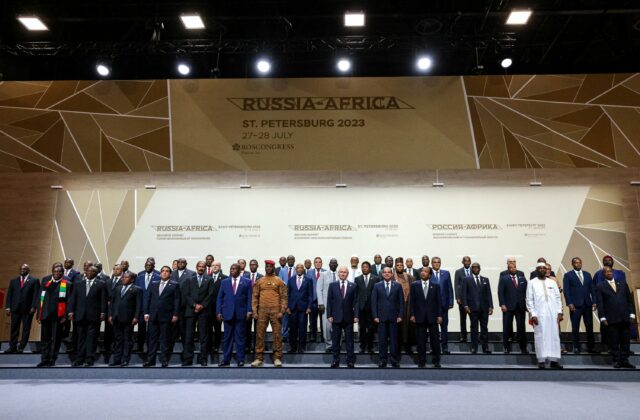

Concerted diplomatic efforts were invested during preparations for the Russia-Africa Summit in St. Petersburg, formally held on July 27 and 28, and President Vladimir Putin was grandstanding, networking and entertaining his guests non-stop from Wednesday afternoon to Saturday evening. His main intention was to demonstrate the width and depth of Russia’s ties with the continent. And as a result, the first major setback was that only 17 heads of state and 10 prime ministers (out of 54 African states) attended the event (The Moscow Times, July 25). The proceedings were so low on content that the awkward mistake of Patriarch Kirill, who addressed Putin at the plenary session as “Vladimir Vasilyevich,” became a major news item (Kommersant, July 27; Topnews.ru, July 27). The main setback, however, hidden by many pompous pronouncements, was the exposed irrelevance of the Soviet heritage of “anti-imperialist” solidarity with Africa and Russia’s inability to address the most urgent challenges the countries of this dynamic and turbulent continent are facing (RBC, July 29; Meduza, July 28).

Deteriorating food security was the key matter that the African leaders wanted to discuss, and Moscow’s decision to cancel the “grain deal,” which had facilitated the export of Ukrainian grain by sea, just a week prior to the gathering in St. Petersburg accentuated their concerns (Republic.ru, July 18; see EDM, July 19). Putin reiterated his reasons for that widely condemned decision and went to great lengths to promise an increase in Russian grain exports and to deliver to the six poorest African countries—Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Mali, Somalia and Zimbabwe—25,000–50,000 tons of wheat, which constitutes 0.1 percent of the Russian harvest, free of charge (Forbes.ru, July 28). The African leaders were not convinced though, and even Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, whom Putin counts among reliable supporters, expressed hope that the grain agreement would be restored (Kremlin.ru, July 28). South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who presently holds the chairmanship in BRICS (a loose grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), was even more direct, asserting that it was not “gifts” that the African leaders came to ask for but the removal of barriers for free grain trade (Meduza, July 29).

Ramaphosa also sought to re-energize the African peace initiative. Thus, Putin held a special session on the Ukraine “problem” late Friday evening but pretended not to hear the proposal for opening the Black Sea to commercial navigation (Kremlin.ru, July 28; Kommersant, July 29). Combat activities in the Black Sea theater are escalating, and Putin used the occasion of a naval parade, to which the presidents of Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Mali and the Republic of the Congo were invited, to emphasize the capacity of the Russian Navy to dominate this region and blockade Ukrainian ports (Izvestiya, July 30). He also asserted that all Ukrainian attacks on Russian defensive lines were repelled with heavy casualties and losses of Western weapons (RIA Novosti, July 29). In fact, the sustained pressure of the Ukrainian offensive threatens to turn small tactical gains into an operational breakthrough, routing the exhausted Russian troops (The Moscow Times, July 27). Ukraine has also developed and produced innovative naval drones, and this not-so-small armada challenges every combat mission of the Russian Black Sea Fleet as well as its bases (Spektr Press, July 24).

Putin was eager to talk about rejecting the unfair world order, countering Western “colonialism” and upholding sovereignty (Russiancouncil.ru, July 25). This dubious discourse finds takers in Africa, and Ibrahim Traoré, the youngish interim president of Burkina Faso, enthusiastically condemned colonial “slavery” and supported the Russian “special military operation” in Ukraine (Svoboda, July 27). It was too transparent, however, for many more experienced African leaders that Russian rhetoric on sovereignty provides camouflage for its policy of conflict manipulation, in which the Wagner Group, discredited as it is, continues to serve as a key instrument (Carnegie Politika, July 27). Yevgeny Prigozhin made a cameo appearance in the corridors of the summit and found it opportune to praise the coup in Niger, seeing it as an opportunity to expand Wagner operations (RBC, July 27; Meduza, July 28). This cynical conflict of entrepreneurialism undercuts the goals of development in the troubled Sahel region, and Libyan Presidential Council Chairman Mohamed al-Menfi reiterated the demand for the withdrawal of all mercenaries from his country (Kremlin.ru, July 28).

Russia cannot reproduce the Soviet policy of bankrolling “friendly” regimes, and neither can it connect with the Chinese policy of investment in resource extraction in Africa (Rossiiskaya gazeta, July 24). Beijing’s attention to African affairs was illustrated by the visits of Wang Yi, reappointed as foreign minister after an opaque cadre reshuffle, to South Africa (where he met with Nikolai Patrushev, long-serving secretary of the Russian Security Council), Kenya and Nigeria—the two states notably absent from the gathering in St. Petersburg (RIA Novosti, July 24). The last stop on Wang Yi’s tour was Turkey, and the problem of reviving the “grain deal” was a key point in his conversation with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Nezavisimaya gazeta, July 27). Putin persists in rejecting these messages, but to show engagement with matters of importance for China, he sent Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu to North Korea to partake in the pompous celebrations of “victory,” which in fact was the signing of an armistice that has held for 70 years (Novayagazeta.eu, July 28).

Putin invested extraordinary personal effort in courting African leaders, but even mainstream Moscow commentators find it difficult to summarize what exactly was achieved (Rossiiskaya gazeta, July 29). The long shadow of aggression against Ukraine cannot be dispelled by upbeat speeches, and Putin’s claims that it was the West that had started the war alert his counterparts to the issues of his progressing detachment from reality. With only a few exceptions, African states prefer to keep their distance from the dangerous global confrontation driven by the war of Putin’s choice, but their “neutrality” is fluid, and the impressions from St. Petersburg have hardly brought them any closer to Russia. The failure of their collective effort at reviving the “grain deal” has certainly left a bitter aftertaste. However, perhaps more important is the first-hand verification of the severe and sustained contraction of the resource base for Russia’s foreign policy. The key word in the African agenda is “development,” which connects directly with the need for investments, and what the African leaders saw in Russia was war-caused disinvestment in economic modernization and human capital. Denial of responsibility is now the key feature of Russian state policy, and partnering with such an irresponsible power is about as sensible as inviting Wagner mercenaries to uphold stability.