HUNGARY’S SOCIALIST GOVERNMENT JOINS GAZPROM’S SOUTH STREAM PROJECT

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 5 Issue: 39

By:

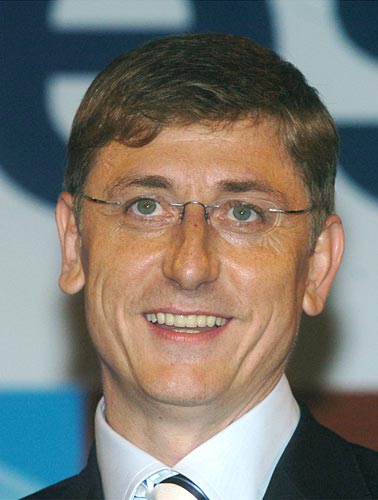

On February 28 Hungary’s Socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany joined Russia’s outgoing and incoming presidents, Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, in Moscow to seal an intergovernmental agreement on Gazprom’s further expansion into European Union territory via Hungary.

Hungary’s privately owned energy company MOL is staying out of this intergovernmental, politically-colored deal. MOL is a partner in the U.S.-backed Nabucco project of the EU. The Hungarian government’s accession to South Stream, however, adds to the recent series of defections from the Nabucco project (see EDM, January 24, 28, 29, February 5, 28).

The agreement just signed envisages building an extension of Gazprom’s South Stream gas pipeline through Hungary. It caps the recent series of deals rushed through by the Kremlin with Austria, Bulgaria, and Serbia, to build pipelines and storage sites for South Stream gas into Europe. These agreements are cementing Gazprom’s monopoly in parts of Europe, precluding alternatives and aborting Nabucco.

Under the agreement, the South Stream pipeline shall enter Hungary from Serbia and apparently continue northward to Austria. However, a westward continuation via Croatia or Slovenia to Italy remains an option. Hungary shall specially create a company with 100% state ownership, to partner with Gazprom for the South Stream project on Hungarian territory. Apparently, the Hungarian Development Bank (100% state-owned) is slated to be the Hungarian partner, whether directly or through a subsidiary. Gazprom and the Hungarian company shall set up a 50%-50% joint venture to build and operate a pipeline and an underground storage site on Hungarian territory.

The respective capacities are projected for “at least” 10 billion cubic meters annually in throughput and “at least” 1 billion cubic meters in storage. The proportions of gas to be consumed in Hungary and to be transited to third countries remain to be determined. The pipeline and storage facility are supposed to become operational in Hungary (as in other South Stream participant countries) by 2013. The investment in Hungary is roughly estimated at $2 billion or €2 billion, to be amortized in 15-17 years, out of South Stream’s projected 30-year lifetime. The technical and commercial feasibility studies for Hungary (as for other countries) are yet to be undertaken.

Further under this agreement, South Stream gas transmission and storage in Hungary shall be entirely separate physically and commercially from MOL’s and any other companies’ pipelines, storages, and market operations. These provisions are potentially damaging to MOL.

The agreement’s signing in the absence of any feasibility study, and the vagueness of its terms (except for the rather precise amortization period, which seems disturbingly lengthy), indicates that the Kremlin and Gyurcsany rushed through the agreement for political reasons. The Kremlin successfully generated a bandwagon effect, in the absence of countervailing offers from Brussels and Washington for the Nabucco countries and their neighbors in the short term. Inasmuch as it strengthens Gazprom’s already heavy dominance and prolongs it for several decades ahead, the South Stream project undermines the energy security of recipient countries and their overall strategic security.

In Hungary’s case, the agreement carries an additional adverse implication. In effect, it launches a process of re-etatization of the energy sector, which Hungary had privatized with notable success in terms of cost-effectiveness and reinvestment capacity for continuing modernization. Hungary’s privatization had become an attractive example for neighboring ex-communist countries (or indeed neighboring Austria) to emulate if they chose. By contrast, energy re-etatization as a spillover effect of South Stream would be a regressive step for Hungary. Moreover, placing this re-etatization process under de facto control of Gazprom poses national security risks beyond the economic ones.

At present, Hungary consumes just under 10 billion cubic meters of gas annually, 80% of which originates in Russia and enters Hungary from Ukraine. The Hungarian demand is expected to grow to 15 billion cubic meters annually by the middle of the next decade. The Nabucco project was designed to introduce some balance into that equation by entering Hungary and Austria from the south with Caspian gas. South Stream, on the contrary, is designed to maintain and prolong that heavy dependence on Russia, not only with regard to volumes, but also by foreclosing the alternative supply route from the south.

In Austria, the OMV state-controlled company’s CEO, Wolfgang Ruttenstorfer, is hailing Hungary’s accession to South Stream, in the expectation of larger deliveries from Gazprom via Hungary to Austria. In his latest interview, Ruttenstorfer sounds eager to turn the capacities of the Baumgarten storage system – the previously designated terminal for Nabucco – over to Gazprom to use for South Stream gas. According to Ruttenstorfer, moreover, the recent accession to South Stream of Bulgaria and Serbia (which opened South Stream’s way into Hungary and Austria) was only natural, reflecting “the Russians’ cultural closeness to Bulgaria and Serbia” (Format [Vienna], February 22-28). At this rate, Hungary’s Socialist government and Austria’s OMV risk find themselves pulled into unwanted cultural closeness with Gazprom from the standpoint of business culture and practices.

(MTI, Nepszabadsag, Dow Jones, February 25-28)