Hybrid Attacks Rise on Undersea Cables in Baltic and Arctic Regions

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 22 Issue: 14

By:

Executive Summary

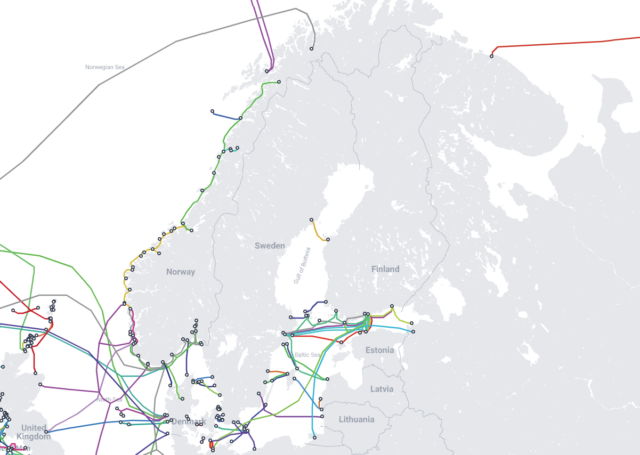

- Russian hybrid attacks targeting critical undersea infrastructure (CUI), particularly fiber-optic cables, have surged in the Baltic and Arctic regions since 2021. These disruptions threaten essential communication channels and expose the vulnerabilities of Northern Europe’s infrastructure.

- Incidents in 2023 and 2024 involving Chinese vessels damaging Baltic subsea cables raise concerns over possible Russian-Chinese hybrid warfare collaboration despite no direct evidence confirming this, complicating Western deterrence efforts.

- Western responses are complicated by the difficulty of attributing attacks and Russia’s use of plausible deniability. Hybrid tactics enable Russia to destabilize a region without entering open conflict.

The Silver Dania, a Russian-crewed cargo ship, was detained by Norwegian authorities on January 31 for suspected acts of sabotage after reports that a fiber-optic cable linked between the Swedish island of Gotland and Ventspils in Latvia had been damaged (TheLocal.no, February 1). After no evidence was found connecting the ship to the damaged cable, the crew was released, and the Russian Embassy in Norway called for an inquiry into the incident (Politiet.no; TASS, January 31). This, however, is not an isolated incident. Russian hybrid attacks on critical undersea infrastructure (CUI), particularly fiber optic cables, are on the rise, particularly in the Baltic and Arctic seas. These cables are not only crucial for internet access, but they are also essential communication tools. Their sabotage, therefore, is highly disruptive. These types of attacks are an easy and cheap strategy for Russia to cause disorder in northern Europe. Unfortunately, deterring Russia is easier said than done.

This rise in Russian attacks has been a trend in the Arctic and Baltic areas since 2021, when a LoVe Ocean Observatory cable went out of service in northern Norway (Institute of Marine Research, November 26, 2021). In 2022, a communications fiber optic cable connecting Svalbard to the Norwegian mainland was also suspiciously damaged (NRK.no, May 26, 2024). This cable was key for Norwegian communications to the mainland and essential for Norwegian space infrastructure (Ibid). Neither incident, however, was immediately labeled as an attack.

While the 2021 and 2022 cases could have been accidental, in 2023, a gas pipeline and data cable of the Baltic Connector pipeline were damaged (Yle.fi, April 22, 2024). Investigators quickly determined that the New Polar Bear, a Chinese container ship, was responsible for dragging its anchor along the ocean floor and damaging both cables while traversing between Russian ports (ERR News, August 12, 2024). While Chinese officials admitted that the vessel was responsible, they claimed it was an accident (Ibid). In 2024, two cables in the Baltic Sea were cut, one connecting Germany to Finland and a second connecting Lithuania to Sweden by the Chinese vessel Yi Peng 3 (ERR News, November 26, 2024).

The 2023 and 2024 incidents involved Chinese vessels, which could indicate increasing Russian-Chinese cooperation on hybrid attacks. There is no evidence, however, to suggest that this cooperation exists, particularly as experts have noted that Russian-Chinese cooperation in the Arctic at large is still relatively limited (IFS Insights, May 2024)

Outside of these direct cable damage incidents, concerns have been raised about Russia using a shadow fleet to map CUI in the Baltic Sea (DR.dk, April 19, 2023). This shadow fleet is made of military and civilian ships, allegedly designed to disrupt wind farms and communication cables and sabotage the Nordic countries.

The question remains about why Russia would use hybrid attacks in the Baltic and Arctic. The rise of attacks on sub-sea infrastructure, particularly in the Baltic and Arctic regions, is beneficial for Russia’s overall strategy. Not only is direct attribution extremely difficult, which makes effective deterrence even more challenging, but such tactics fall beneath the threshold of armed conflict. In remaining underneath this threshold, Russian actions present a dilemma to Western governments. If they respond aggressively, Russia can claim it is being harassed. By not responding, however, Western states may incentivize increasing attacks of this kind. Particularly in the case of sub-sea infrastructure, where it takes time to investigate the cable rupture, it is hard for a Western government to claim that an attack was intentional and even more challenging to attribute the damage to a specific actor. In other words, Russia can simultaneously employ plausible deniability and avoid outright war while also causing serious disruption to Western societies.

Hybrid attacks also allow Russia to test and probe the defenses in the Baltic and Arctic. The aim is to see how resilient northern European countries are to non-traditional attacks. From Russia’s perspective, such attacks are relatively cheap and easy to conduct. It is difficult to prevent ships from dragging their anchors, particularly if the ship does not immediately cause suspicion.

As deterring Russia’s behavior directly remains difficult, there is no reason to assume that hybrid CUI attacks will not continue. Some evidence exists, however, that states in the Baltic and Arctic areas are experimenting with new methods to disincentivize such hybrid attacks. For example, the European Union released a statement on December 26, 2024, claiming it would strengthen its efforts to protect undersea cables using better detection technology (European Union External Action, December 26, 2024). Additionally, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) announced on January 14 the deployment of a new Baltic Sentry “to deter any future attempts by a state or non-state actor to damage critical undersea infrastructure” in the Baltic Sea (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, NATO, January 14). Individual states can also deter Russian behavior (European Union External Action Service, December 26, 2024). For example, when the Finland-Estonia electric link was disrupted in December 2024, the Finnish Border Guard quickly detained an oil tanker flying the Cook Islands flag and brought it into Finnish territorial waters (Yle.fi, December 26, 2024).

Whether these or other deterrence measures discourage Russia’s will to engage in hybrid attacks is still an open question. While the effort continues to be lower than the cost, Russia has every rationale to continue disrupting CUI in the Baltic and Arctic regions.