In Kazakhstan, Generation Z on Alert Over China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 2

By:

Introduction

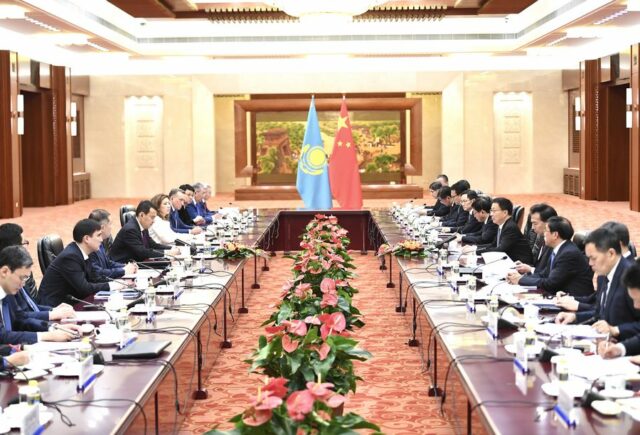

Kazakhstan is seeking to boost bilateral ties with China, which is reopening international travel after abandoning its Zero-COVID policy late last year (Kazinform, January 17). However, “Kazakh Gen Zs” born in the 2000s are worried about their country’s increasing dependency on China. [1] “China is our ally and [our] enemy, the villain, and thanks to this, [our] economic lives,” wrote a second-year student who has studied in one of the private universities in Kazakhstan’s largest city Almaty. The topic of China has evoked a wide range of thoughts and opinions from students, and a study of twenty essays on China written by Kazakhstani Generation Z reveals some of their more nuanced perceptions of China. [2]

Mixed Feelings

Across their essays, the representatives of Gen Z internalized the pragmatic balance promoted in Kazakhstan’s official foreign policy (President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, March 9, 2020). Sandwiched between Russia and China, Kazakhstan has endeavored to balance friendly relations with its close neighbors and with western countries in order to lessen the effect of its landlocked geography. Students expressed positivity about the fact that Kazakhstan borders one of the world’s most powerful economies, China. These students appreciated that the solid Chinese economy enables Kazakhstanis to conduct import business with China, receive quality Chinese higher education, and purchase cheaply produced consumer goods. Gen Zers, who grew up during the oil boom in Kazakhstan in the 2000s, are clearly inclined to support a booming market economy with a strong flavor of consumerist culture (Voices of Central Asia, March 21, 2019). Additionally, some students expressed a desire to travel, study and work in China. However, despite these perceived advantages, students felt pressured as Kazakhstan is located between two giants, China and Russia.

Gen Z was particularly concerned over the increase in Chinese investment in developing economies, including Kazakhstan, which they perceived might translate into political influence. They fear this will give leverage to Beijing and make Kazakhstan more economically dependent on China. The students expressed beliefs that China absorbs countries into its domain by lending to governments that are unable to repay these loans. These loans must be settled by other means. With Kazakhstan being the sixth largest recipient of Chinese loans, right after Angola, Brazil, and Indonesia, economic dependence is a matter of sovereignty concern (Aid Data, September 2021). Also, the students expressed concern about statements made by China, which views its neighbors with “pride and condescension.” Among many examples, a privately owned Chinese website Sohu ran an article entitled “Why Is Kazakhstan Eager To Get Back to China?” claiming that the Central Asian country was historically part of China and asserting that Kazakh tribesmen once pledged their allegiance to the Chinese emperor (VOA Chinese, April 15, 2020). In response, the Foreign Ministry registered its concern with the Chinese Ambassador Zhang Xiao over the story (Gov.kz, April 14, 2020).

The undergraduates who were surveyed also expressed concern over China’s competition with the West for “the world’s great power position” and over issues such as Taiwan, which pose a challenge to Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy that seeks to balance relations with Russia and China. Officially, Kazakhstan is committed to a “One China Policy” and considers Taiwan an unalienable part of China (The Astana Times, August 4, 2022). The students clearly regarded China’s growing confidence, its increasingly active role in the international arena and its growing global stature as worrisome developments for states that do not desire to follow China’s international lead.

Stereotypes Have Deep Hold

Despite these pragmatic views, Sinophobia is still apparent in the attitudes of Gen Z Kazakhs toward China. Some of the students used derogatory and offensive stereotypes to describe China and its people as spreaders of exotic diseases, eating insects, not being clean, and bringing “filthiness” to Kazakhstan. They also wrote that democracy and human rights are ‘alien’ concepts to China. They expressed dislike for China because of its unjust and cruel policies, including the surveillance of its people. The extent of corruption and nepotism at the top levels of Chinese politics and business was also raised. One student noted that Chinese workers face unemployment and low-paid working conditions due to their large population, equating conditions to “modern-day economic slavery.” Despite such negative perceptions, China remains attractive to students for short-term visits, but they do not wish to reside there permanently because of fierce competition in the job market. The students felt that China is a country that aggressively builds a positive image of itself and its development, but things are very different on the ground.

The aforementioned views of China also seem to have an implicit effect on Gen Z through their increased consumption of video content on social media. This potentially shows a lack of impact on Chinese soft power spending despite considerable funds allocated to cultural diplomacy in Kazakhstan. For example, one student wrote, “when we think of China, we can think of the huge population, dirty air, and cruel laws.” They disliked careless attitudes toward air pollution, useless waste and in particular, the gray smog in Beijing. Paradoxically, others tended to like strict laws and wished they could be applied in Kazakhstan, where the students perceived them as conducive to development.

Simultaneously, students were fascinated by China’s culture and considered its people creative and hardworking. Students recognized the great inventions of Chinese scholars, and Gen Zs often watched videos where Chinese people expressed themselves creatively. Students particularly liked the Chinese studious education system that seemly produces smart minds from early school years. Additionally, diverse cuisine, great movies, and technological advancements were all appreciated.

Conclusion

Not to be missed in their essays, the students particularly condemned the re-education programs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) being administered in Xinjiang. [3] Students were genuinely perplexed about how such cruelty could be perpetrated by a country against its own Muslim citizens. Students write that Muslims, including ethnic Kazakhs, have been beaten, imprisoned, or killed, and they assess the CCP policy towards the ethnic minorities of Xinjiang as morally inhumane (China Brief, May 15, 2018). They were also frustrated that the plight of those victims in so-called re-education camps had not received greater worldwide attention. Acknowledging the plight of those who have undergone treatment in re-education camps is an expression of solidarity with those who share similar Islamic identities. Accepting that China is a great world power with the world’s fastest-growing economy, students expressed caution about the growing dependence of Kazakhstan on China.

Berikbol Dukeyev, a native of Kazakhstan, completed his Ph.D. in politics and international relations from the Australian National University (ANU) in 2022. His research interests include the intersections of politics, society, and security. His publications have appeared at OpenDemocracy and Central Asian Affairs. Previously, he was a Sessional Academic at ANU, a Central Asia Fellow at George Washington University, and a Research Fellow at the Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Notes

[1] Paolo Sorbello, “The Sorrows of Kazakhstan’s Generation Z,” The Diplomat, January 30, 2018.

[2] The essays cited here are by first and second-year university students in Kazakhstan. The students produced handwritten essays on their views of China in December 2022 in Kazakh or Russian languages. These essays were written anonymously without collecting any identifying information.

[3] James Millward, “China’s New Anti-Uyghur Campaign How the World Can Stop Beijing’s Brutal Oppression,” Foreign Affairs, January 23, 2023.