Infrastructure Development in Tibet and its Implications for India

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 22

By:

Introduction

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) considers Tibet an intrinsic part of Chinese territory, which it has controlled since the early 1950s. When the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) entered the region in 1951, Tibet was sparsely connected, both internally and with China proper. Today, it is well connected by a comprehensive network of highways, railroads, and air routes. This dual-use infrastructure (along with China’s recent military modernization and ongoing PLA reforms) helps China to manage the threats emanating from its unresolved border dispute with India, which is the PRC’s secondary strategic direction after Taiwan and the Western Pacific [1]. Infrastructure development also supports China’s efforts to maintain internal stability within the restive Tibetan region.

This article surveys the civilian infrastructure that China has built in Tibet over the last two decades, including roads, railroads and airports – all of which are dual-use in nature. In doing so, it also briefly discusses the implications of these developments for China’s unresolved border dispute with India.

Infrastructure Development

The total road network in Tibet in 1959 was only 7,300 km (CGTN, March 25, 2019). in 2021, however, Tibet’s road system has increased to 118,800 km, which means it has expanded approximately 4.93 km per day since 1959 (State Council of the PRC, May 21). Although the central leadership has invested heavily in improving Tibet’s infrastructure and connectivity, the speed and scale of projects has only really accelerated since 1999, when China launched its “Go West” campaign as a part of the western development strategy (西部大开发, xibu da kaifa) (China.org.in, January 17, 2005). Under its 10th and 11th Five-Year Plans, China invested RMB 31.2 billion (US $4.2 billion) and RMB 137.8 billion (US$ 21 billion) to undertake 117 and 188 key infrastructure and development projects in Tibet (Tibet.cn, December 3, 2015). Under the 11th Five-Year plan, the center encouraged Chinese cities and companies to assist Tibetan cities and counties by providing them aid under the 101 Aid Program (对口支援, dui kou zhi yuan) (State Council Bulletin, March 14, 2006).

This emphasis on infrastructure development for the region has continued under General Secretary Xi Jinping. During the 2020 Work Symposium, Xi cited the need for “promotion and construction of a number of major infrastructure and public-service facilities around the Sichuan-Tibet railway line and other roads, and to build more unity lines and happiness roads (in and connecting the region)” (Xinhua, August 30, 2020). He highlighted this as one of the five developments to improve people’s livelihood and unite people’s hearts (五大部署 改善民生、凝聚人心, wuda bushu gaishan minsheng, ningju renxin) (Court.gov.cn, August 30, 2020). Under the current 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP), China aims to spend over RMB 190 billion (approximately $30 billion) on infrastructure projects in Tibet between 2021 and 2025 (Xinhua, March 6). The regional transportation department states that by 2025, Tibet will exceed 1300 km of expressways, and have over 120,000 km in highways total.

Tibet-related projects in the 14th FYP include the Ya’an to Nyingchi phase of the Sichuan Tibet Railway line, preliminary work on the Hotan-Shigatse and Gyirong-Shigatse (China-Nepal border) railway lines, and the Chengdu-Wuhan-Shanghai high-speed railway network (Gov.cn, March 13). The plan also mentions upgrading the national highways G219 and G318 – both of which run parallel to the China-India border near Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

The following table outlines China’s ongoing and completed road and railroad projects in Tibet. It includes national highways and railroads connecting China Proper to Tibet, Tibet to Xinjiang, and the intra-province network.

Table 1: Tibet’s Roadway and Railroad Network

| Project Description | Project Details |

| Roadways | |

| National Highway G6/ G109 | G109 connects Beijing to Lhasa. The G6 is the portion that connects Lhasa to Xining in Qinghai. The construction for the 1,897 km Xining-Lhasa stretch began in February 2018 [2]. |

| National Highway G219 / G564 | G219 connects Xinjiang to Tibet. It originates from Yecheng in Xinjiang and terminates at Lhatse in Tibet. The road was constructed in 1957, however, under 13th FYP, China started upgrading it. G564 will emerge from G219 and will reach Purang near the China-India-Nepal tri-junction. It will pass between Mansarovar and Rakshas lake. |

| National Highway G318 | The 14th FYP discusses the extension of G318. G318 connects Shanghai to Tibet through Chengdu in Sichuan. It then enters Nepal near Zhangmu near the China-Tibet border. The road passes through Nyingchi, close to the China-India border near Arunachal Pradesh, and a feeder road originating from G318 also reaches opposite Tawang near Cono county. |

| National Highway G317 | G317 originates in Chengdu, Sichuan and runs parallel to G318 through Chamdo and Nagqu before meeting G109- which meets G318 at Lhasa. |

| National Highway G 580 | G580 is currently under construction, and on completion, will connect Ashu to Kangxiwar through Hotan. It would be completed by 2022. |

| Other Important Highways | G315 (East-west highway connecting Qinghai and Xinjiang); G314 (connecting Urumqi and Khunjerab Pass); G216 (linking northern Xinjiang to Kyirong County in Tibet by meeting G218 near Hejing county in Xinjiang). |

| Other Important Roads/Provincial Highways/Feeder roads | Pei-Metok Highway (Nyingchi to Mehtok), Lhasa-Nagqu highway, Nagqu-Ngari Ali Highway, Bome to Medok Highway, Qiongjie to Cona Highway, Bayi-Manling Highway, G214 Kunming-Lhasa Highway and more. |

| Railroads | |

| Sichuan-Tibet Line | Divided into three sections: 1) Chengdu to Ya’an Section (140 km): Opened in December 2018 2) Lhasa to Nyingchi Section (435 km): Opened in June 2021 3) Ya’an to Nyingchi Section (1, 011 km): Estimated to finish by 2030. |

| Qinghai-Tibet line | The construction began in 2001 and was completed by 2006. This line was further extended up to Shigatse in 2014. The only railway that connects China proper to Tibet. |

| Shigatse-Yadong Extension | The Lhasa-Shigatse line will be further extended from Shigatse to Yadong County. Yadong County is the last county on the China-India border near Sikkim and adjacent to India’s Nathu la pass. |

| Shigatse-Gyirong-Katmandu (Nepal) | To be completed by 2022. |

| South Xinjiang-Tibet Loop | Hotan-Shigatse line (825 km – under construction) largely follows G219 route – unknown if it would enter Aksai Chin region like the highway, Hotan-Ruoqiang line (Xinjiang – under construction), Ruoqiang-Korla Section of the Golmund-Korla line (in operation since 2014) and Gomund-Lhasa Section of the Qinghai-Tibet line (in operation since 2006).

Together, these lines form the Tibet-South Xinjiang loop connecting most major cities in the region. |

| Other Important lines | Yunnan-Tibet line (still planned); Dunhuang-Golmud Railway (opened in 2019). |

Source: Compiled from multiple sources including the TAR Government Work Reports from 2009-2021. https://www.xizang.gov.cn/zwgk/xxfb/zfgzbg/

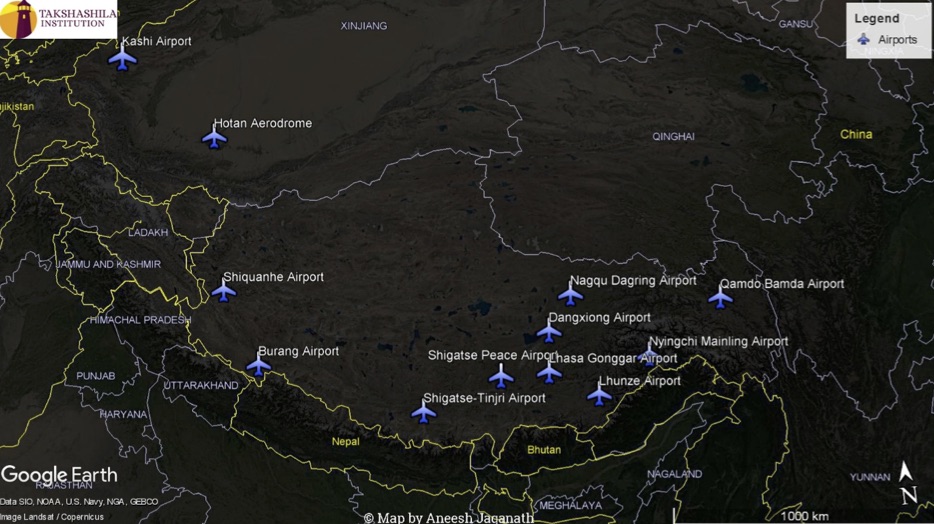

Furthermore, the 14th Five Year Plan (FYP) also sets out that China will develop the Chengdu-Chongqing “world-class” airport cluster, and expand Chongqing Jiangbei International Airport (Gov.cn, March 13). The FYP states that China will add 30 more civilian transport airports, but does not specify the location of these facilities. The construction of these 30 airports will be in addition to the 12 existing operational or under construction airports in Tibet and the South Xinjiang region around the Indian borders.

Impact on Border Dispute with India

Mobilization of Forces for Counter-attack Campaigns

Chinese military texts describe an approach to securing its territory through ‘border area counter-attack campaign’ (边境地区反击战, bianjing diqu fanji zhan). As international security expert M. Taylor Fravel argues, these campaigns occur in two phases. The first phase begins with defensive operations to create favorable conditions for the counterattack after the adversary’s initial strike. The second phase includes counter-attacking after main force units have arrived in the theater of operation from the interior [4]. For China, a contingency with India would play out in Tibet and the Southern Xinjiang border regions involving the Western Theater Command’s 76th and 77th Group Armies, as well as forces from the PLA’s Central and possibly Southern Theater Commands.

The improved infrastructure that China has built over the last two decades makes mobilization of the armed forces to counter India relatively faster and easier. For instance, the Sichuan-Tibet railway connects Chengdu to Lhasa. Chengdu and the adjacent municipality of Chongqing host the PLA’s 77th Group Army, which would be one of the first units to mobilize after the Tibet and Xinjiang Military Districts in the event of an escalation of conflict with India. The average travel time from Chengdu to Lhasa through the existing road and railway network is around 40 hours or more. However, upon completion, the Sichuan-Tibet railway will reduce this trip to 15 hours – making mobilization much quicker. This is just one example of the PLA’s improving capacity for mobilization using China’s improved connectivity in and around Tibet. As highlighted in table 1, China is raising multiple road and railroad lines to connect Tibet internally, Tibet with China proper and Tibet and Xinjiang autonomous regions. This rail and railroad network, on completion in the next 10- 15 years, would help the PLA, the People’s Armed Police (PAP), the border defense forces and the militia to mobilize quickly in case of a contingency on the border with India.

Logistics Supply during Protracted Conflicts

China and India have been involved in multiple stand-offs along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh over the past 20 months. Both countries have also forward deployed their forces along the entire border since the beginning of the ongoing stand-off since May 2020. With the recent failure of 13th Corps Commander-level talks in October 2021, it looks like the forces will have to withstand another harsh winter of forward deployment along the border.

Table 1 highlights that China has constructed national and provincial highways and connected the important border points to these highways and major Tibetan towns with feeder roads. As witnessed over the course of the past twenty months, these feeder roads help ensure forward-deployed troops receive timely resupply of food, ammunition and other essentials despite tough terrain and harsh conditions. This is unlike the Indian side, which is still trying to strike a balance between national security and environmental concerns – impacting its combat ability and preparedness (The Times of India, November 10).

In addition to facilitating mobilization of forces and logistical supply, improved infrastructure also helps China to integrate the restive Tibetan region with China proper and monitor cross-border Tibetan migration, which could impact internal stability and security.

Conclusion

Although the CCP has ruled Tibet since the early 1950s, the scale and scope of regional development increased only after the PRC launched the Go West campaign in 1999. Under President Xi Jinping, China has continued building a vast network of infrastructure projects like roads, railroads and airports in Tibet – all with dual-use capabilities. The combination of the dual-use civilian infrastructure development and the recent military modernization has helped China to gain an operational advantage along the border with India.

Besides roadways and railways, China’s three major arteries (oil pipeline, internet and power connectivity) and the latest “well-off villages in border areas” have also played a vital role in stabilizing the region and securing the border. Part II in this series focuses on these developments and their impact on the border dispute with India.

Suyash Desai is an Associate Fellow, China Studies Programme, The Takshashila Institution, India. He studies China’s defence and foreign policies and also writes a weekly newsletter on the Chinese armed forces called the PLA Insight. This article is inspired by his upcoming research project covering China’s civilian and military developments in Tibet and its implications on India.

Notes

[1] M. Taylor Fravel, “China’s “World-Class Military” Ambitions: Origins and Implications,” The Washington Quarterly, March, 2020 43:1, 85-99. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0163660X.2020.1735850?journalCode=rwaq20

[2] The construction of G6 was started after the 2017 China-India Doklam stand-off. However, it was planned long before the standoff.

[3] The data for this map is compiled from multiple sources including the TAR Government Work Reports from 2009-2021 https://www.xizang.gov.cn/zwgk/xxfb/zfgzbg/ ; Sim Tack, “A Military Drive Spells Out China’s Intent Along the Indian Border,” Stratfor, September 22, 2020, https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/military-drive-spells-out-chinas-intent-along-indian-border; Tyler Rogoway, “Tracking China’s Sudden Airpower Expansion on its Western Border,” The Drive, June 16, 2021. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/41065/tracking-chinas-sudden-airpower-expansion-along-its-western-border

[4] For more see M. Taylor Fravel, “Securing Borders: China’s Doctrine and Force Structure for Frontier Defense,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 30:4-5, 722-723. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01402390701431790