Iran and the Anti-Islamic State Coalition

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 21

By:

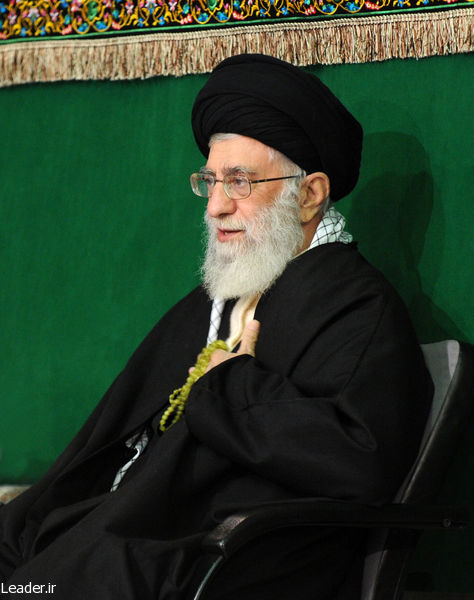

On September 15, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, announced on national TV that he had ruled out Iran’s participation in the U.S.-led military coalition to combat the Islamic State organization, previously the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria – ISIS (IRIB, September 15). Khamenei’s rebuff came as the U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry, also ruled out the possibility of Iran joining the coalition, although he said he recognized that Iran could play an important role in defeating the militant organization (al-Jazeera, September 19). While the United States took issue with Iran’s support for the Syrian government, the Iranian leader questioned the real objective of the U.S.-led military alliance. He described Washington’s strategy as a “hollow and self-serving” move to exert power, which, he also said on his Twitter account, has in fact ironically undermined Washington’s own interests in the region: “If the United States enters Iraq and Syria without permission, they will go through the same problems as they did over the past ten years in Iraq.” [1]

Kerry’s recognition of Iran’s important role in the fight against the Islamic State organization would suggest an American willingness to collaborate with Iran on a possible joint military action. This willingness is bolstered by the latest revelation that, in mid-October, President Obama had secretly sent a letter to the Supreme Leader, highlighting the countries’ shared objective in defeating the Islamic State organization, though this would be conditional on the United States and Iran reaching a comprehensive agreement on the future of its nuclear program (Wall Street Journal, November 6; Tabnak, November 7).

However, in reality Washington and Tehran continue to indirectly cooperate in Iraq, with the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Qasem Soleimani, leading a coalition of Iraqi and Iranian ground forces to push back the Islamic State organization and clearing the way for U.S. airstrikes. Yet regardless of such unofficial cooperation, an Iran-U.S. alliance would not have been possible without consent from Saudi Arabia, which would have refused to join the coalition with Iran overtly on board. As a Shi’a-majority country and an ally of Syria, Iran would also obviously complicate Washington’s attempt to reach out to Sunni Arab states in order to win a “coordinated military campaign” against the Salafist organization (Jerusalem Post, October 20). In many ways, the Sunni presence remains central to legitimize the coalition. Another major push back against Iran overtly joining the coalition would have come from the U.S. Congress, a development that could have certainly complicated the ongoing nuclear deal as the negotiations enter a crunch time with the looming November 24 deadline.

Equally important to note is that Iran’s refusal to join the coalition appears less ideological and more pragmatic. First off, Iran views the Islamic State organization as a military and a sectarian threat and it also sees the Salafist group as a terrorist organization with a radical anti-Shi’a worldview. Second, similar to the United States, Iran views the Islamic State organization as a major danger to regional security, in particular, due to the potential for sectarian violence to be unleashed by the radical militants. That said, Iran is equally concerned with the return of the U.S. military in Iraq. From Tehran’s perspective, the anti-Islamic State coalition serves as a cover for a renewed U.S. military adventure in the region (Shafaqna, September 10).

With memories of 2001, which saw the United States fail to recognize Iran’s significant contribution to the downfall of the Taliban, still fresh in minds of many in Tehran, Iran is wary of a hidden U.S. agenda (Fars News, September 27). It views anti-Islamic State military operations as a smokescreen for a broader conflict, which is to overthrow Bashar al-Assad and ultimately undermine Iran’s influence in the region (IRNA, October 11; Keyhan, October 10). As the Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, has argued, the coalition airstrikes are primarily “theatrical” displays which have not curtailed the spread of the Islamic State organization in the Iraqi territories (Jerusalem Post, October 18; Tasnim, October 12; Yalasarat, October 10).

While such claims confirm a conspiratorial perspective among Iran’s officials, the above also echo similar concerns Tehran had when another coalition was organized in 2003. The earlier coalition toppled Saddam Hussein, Iran’s archenemy, but it also provided the United States with a new military base to contain Iran. Yet, it is not the containment of Iran that remains a problem for Tehran, but, more importantly, the instability that the U.S. military intervention causes in the region as a result. If anything, the American military operations in Iraq and Syria have in fact increased the threat of terrorism – as the rise of the Islamic State organization best exemplifies – and more importantly the prospect of sectarian conflict in the region.

Finally, while Tehran views the anti-Islamic State coalition, which includes Iran’s main rival, Saudi Arabia, as a means to sideline Iran and its influence in Syria, and in turn weaken the Assad regime, it is on the domestic domain where Iran’s anti-coalition politics ultimately play out. With hardliners entrenched in the country’s intelligence and military complex, with a further base of support in the parliament, the decision to cooperate with the United States would entail too much of a political risk for the Supreme Leader. Moreover, with the new presidency of Rouhani, the attempt to reach a nuclear deal with the United States and its allies has already been a difficult challenge, as the hardliners continue to resist all forms of negotiations with the West. Although Tehran exerts a great deal of influence in Iraq and Syria, best demonstrated by its recent push for a more stable and inclusive government in Baghdad, the faction-ridden politics in Iran involve considerable risks on the domestic level with increased strife over key foreign policy issues, including a temporary military alliance with the United States (Quds Online [Iran], October 6).

As an implicit rule, it may best serve both Washington and Tehran if their joint fight against the Islamic State organization continues on the level of indirect and unofficial military and intelligence cooperation, since both have too much to risk by forming an alliance.

Nima Adelkah is an independent analyst based in New York. His current research agenda includes the Middle East, military strategy and technology, and nuclear proliferation among other defense and security issues.

Note

1. Please see www.twitter.com/khamenei_ir.