Iran’s Changing Regional Strategy and Its Implications for the Region

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 10

By:

In a typical gesture of defiance, which has signified allegiance to Iran’s revolutionary credentials since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, General Abdullah Araqi, the lieutenant commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), stated the following at a public event in early May: “Today, the world arrogance [the United States] is present in the region, has deployed its warships in the Persian Gulf and has military bases in the regional states, but we are not afraid of this presence and its so-called options on the table” (Fars News, May 7). While this show of defiance may have Iranians as the main target audience, Araqi’s statement also says something central about how Iran perceives its core national interest: standing firm against a U.S. military presence in the region, which it views as an existential threat to the Islamic Republic. Beyond ideology, Iran’s regional policy is driven by fears of a U.S. invasion or a U.S.-orchestrated military attack by a regional power, with Iran’s nuclear sites as the main target. In an attempt to diminish the prospects of a military attack, Tehran has, in recent years, adopted several regional strategies that are intended to contain this perceived threat.

Tehran has undeniably struggled to define a clear strategy, with Iranian officials attempting in various ways over time to establish a coherent defensive posture to prevent a perceived U.S. attack, while also responding to the fallout from various issues, such as the Syrian conflict. At the same time, Iran’s regional strategy has been contingent on shifting geopolitical situations, which has, at times, allowed Iran to expand its sphere of influence and others to undermine Iran’s position in the region. In response to the latest developments in the greater Middle East, and particularly to the rise of the Islamic State as a major sectarian and military threat to the Islamic Republic in 2013, Iran has adopted a new strategy. The latest move is one among the four historical phases in Iran’s regional strategy since the end of Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), which are as follows.

Four Strategic Phases

The first phase began with Hashemi Rafsanjani’s presidency (1989-1997), continued during the reformist period under Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) and ended with the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. During this period, Iran’s regional strategy included efforts to rebuild relations with Arabian states, in particular Saudi Arabia, while reaching out to new Muslim-majority states that were formed after the collapse of the Soviet Union, such as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. In addition, after the September 11 attacks, Iran sought to build new cooperative ties with the United States, as shown by Iran’s tacit support for the U.S. removal of the Taliban in Afghanistan, a development that Tehran viewed as being to its advantage.

The second phase, which ran from 2003 to 2009, was defined by the U.S.-led toppling of the Baathist regime in Iraq and the subsequent rise of Shi’a political parties to power in Baghdad in 2004, causing a sharp divergence between U.S. and Iranian interests in the region. With Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s electoral victory in 2005 and the hardliners’ monopoly over the government, in particular its foreign policy, Iran took advantage of the changing situation in the region, particularly the civil war in Iraq, by establishing new alliances and reaffirming older networks that stretched from Lebanon and Syria to Iraq. In addition, the 2006 Lebanon war (a.k.a. the “July War”), which ended with Hezbollah surviving massive Israeli attacks, created new cross-sectarian support in the region for Iran, with Ahmadinejad gaining popularity in the streets of Cairo and Istanbul for his anti-Israel rhetoric. Iran’s controversial but increasingly developed nuclear program only enhanced its leverage as the government continued to use the nuclear issue to bolster its domestic support. This phase marked the Islamic Republic’s highest level of influence in the region.

The disputed 2009 elections heralded the third phase of Iranian foreign policy when the Islamic Republic faced a domestic and foreign crisis of legitimacy and growing political dissent at home. In post-2009 election period, support for the nuclear program eroded due to internal politicking over the impact of sanctions imposed because of the nuclear program and Ahmadinejad’s mismanagement of the nuclear talks and economy. Arab neighbors, wary of Iran’s nuclear program, continued to view Iran as a regional hegemonic force; this view spread from the palaces to the streets with the start of the Syrian civil war that followed the 2011 uprisings.

Syrian Conflict and Fresh Realignment

The start of the Syrian conflict, beginning in early spring 2011 with armed conflict between the military of President Bashar al-Assad and rebel forces, forced Iran to undertake a forth phase of foreign policy, based around a program of extensive and expensive economic and military support for Damascus. The immediate consequence of the new Iranian regional strategy to support al-Assad’s regime led to a sectarian backlash, the extent of which, Tehran may not have originally anticipated. Iranian assistance for pro-government militias and Damascus’ increasing military dependence on Iran, together with the presence of the Lebanese Hezbollah in Syria, revived sectarian tensions across the region, in particular in the Levant, Egypt and Gulf countries.

While the 2006-2007 Iraq Civil War was primarily limited to Iraq and had limited regional repercussions, the Shi’a-Sunni violence in Syria became a full-blown regional sectarian conflict as well as spawning militant organizations, such as the Islamic State. As a result, by early 2011, Iran had largely lost Sunni popular support, with Tehran-backed al-Assad widely viewed as the most hated Arab figure in the Sunni world, particularly in Persian Gulf states, such as Qatar, where most financial support for anti-Assad groups originated.

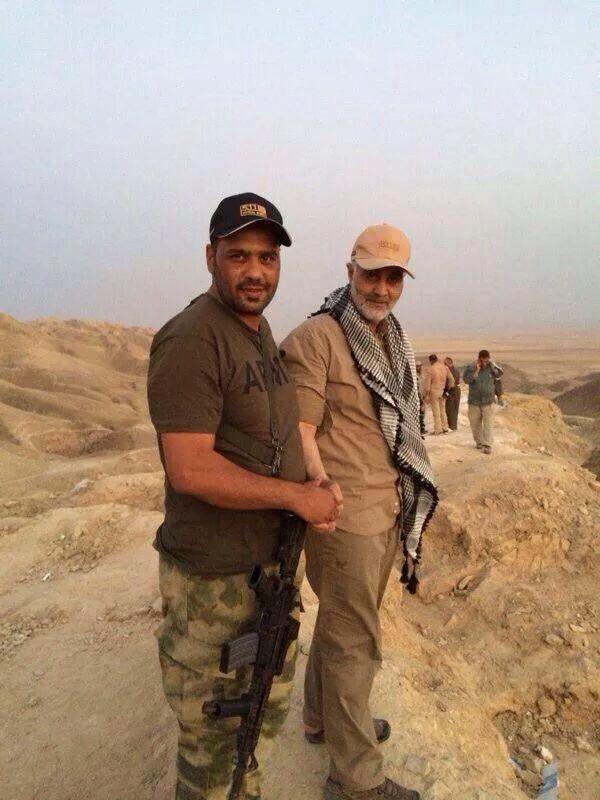

The Islamic State’s shocking capture of the key Iraqi city of Mosul in June 2014 and the group’s (partial) takeover of Iraq’s al-Anbar province forced a fresh shift in Iran’s strategy, introducing a new phase. This time, however, the focus was not to expand Iran’s sphere of influence, but to focus more on targeted interventions to rebuild Shi’a alliances in Iraq, notably to defend Baghdad, and alliances with Iraq’s Kurds to defend the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, Erbil. The conflict in Iraq also became a proxy war between Iran and wealthy Sunni states and individuals based in the Gulf, possibly including the Saudis. The additional case of Yemen is unique in the context of Iran’s new Shi’a-focused alliance building strategy. This is largely due to the geographical distance and difficulty in stationing military officers so close to Saudi Arabia. While there are earlier reports of secret meetings between the Shi’a Houthis rebels and IRGC and Hezbollah figures along the Yemen-Saudi border, stationing IRGC personnel in Yemen would be replete with challenges (al-Arabiya, December 13, 2009). Iran’s military intervention in the form of support for the Houthis, therefore, has therefore primarily focused on the Quds Forces smuggling weapons to the rebels through arms-carrying vessels, although there are reports of Hezbollah operatives actively assisting the Houthis in Sana’a (al-Jazeera, March 26; al-Sharq al-Awsat, September 27, 2014). While General Qasem Soleimani of the IRGC has emerged as the key Iranian figure in charge of military and policy decisions over Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, Iran’s military operational involvement has included other IRGC officers as military advisors, largely in Iraq and Syria (Terrorism Monitor, July 10, 2014).

The most significant feature of the latest strategy is the rapprochement with the West and other regional powers, a process that began, openly and surely, with the electoral victory of relatively moderate President Hassan Rouhani in 2013. Rouhani and his new administration have not only sought to rebuild relations with Iran’s neighbors, but also to agree on a nuclear deal with the aim of doing away with the sanctions and fixing Iran’s ailing economy. With the hardliners marginalized in Iranian politics, Iran’s regional strategy continues to foster détente and yet bolster “the sphere of national interest” (howzeh manafe-ye meli) by protecting the country from its external enemies, particularly Sunni militancy.

The Impact of the New Strategy on the Region

The main strategic objective of the Islamic Republic remains to formulate a defensive position to thwart military attacks from the United States or Israel. Tehran is aware that, in order to create and foster such defensive posture, it has to support its Shi’a and Sunni allies, such as the Kurds, which entails engaging in multiple hot or cold conflicts. At the same time, complicating Iran’s strategy, is that distrust is common among pro-government factions in Iran, as well as confusion (not confined to Iran) over the United States’ own regional strategy.

According to Hussein Amiri, a conservative analyst writing for Gerdab, a hardliner website associated with the IRGC’s defense headquarters, the U.S. strategy in the Middle East has shifted towards Arab monarchies since 2011’s popular uprisings (Gerdab, April 29, 2013). Amiri viewed the new U.S. strategy as an attempt to preemptively tackle the threat of monarchies collapsing throughout the region, and has focused in particular on the survival of Saudi Arabia, using the monarchy as its “military muscle” to advance its economic and military interests in the region. In this view, U.S. support for the Saudis also assures the balance of power in a region where Iranian influence is steadily increasing. Alleged U.S. attempts to topple the al-Assad regime, Tehran’s key regional ally, as a way to limit Iran’s influence in the region, also play an integral role in hardline views of the U.S. strategy in the Middle East (Jahan News, January 14, 2014). Writing for the Hamshahrionline, Gholam-reza Karimi, a political scientists based in Iran, meanwhile argues that the United States is determined to maintain the sanction regime imposed on Iran for its nuclear program (Hamshahrionline, May 12). According to this view, Iran should remain vigilant as the United States cannot be trusted since it ultimately seeks regime change.

Iran’s new strategy still reflects an existing mistrust of the United States. What is different, however, about the latest strategic change is that Iran’s military operations threaten to enhance sectarian sentiments not only in the region, but also beyond, among the Sunni diaspora in Europe, Australia and North America. There is also the risk of an increase in proxy wars between Iran and its Sunni Arab regional rivals, especially Saudi Arabia. The new Saudi Arabian monarchy with its hardline regional policy against Iran, as demonstrated by its military operations against the Houthis since early spring, underline the threat posed by growing proxy conflicts. Iran’s allegedly continuous cargo shipment to Yemen, for example, could potentially lead to the outbreak of military conflict either in the Persian Gulf or the Gulf of Aden, in particular near the rebel-held Yemeni port of Hodeidah (al-Jazeera, April 29; al-Jazeera, May 12; Ya Libnan, May 10). In light of the ongoing and unpredictable nuclear talks, Iran’s new strategy, which is partly driven by defensive objectives in response to wider changes in the region, signals an insecure future for the Middle East.

Nima Adelkhah is an independent analyst based in New York. His current research agenda includes the Middle East, military strategy and technology, and nuclear proliferation among other defense and security issues.