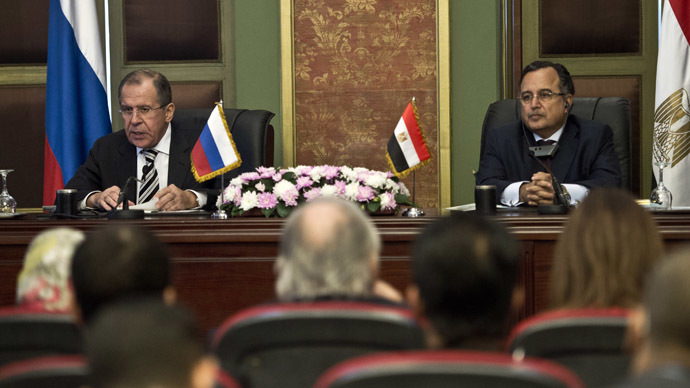

Is Egypt Russia’s Next Major Middle Eastern Arms Customer?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 91

By:

Today, Russia is being associated almost exclusively with the crisis it has generated in Ukraine. But that is a myopic and excessively complacent view. Indeed, Russia is carrying on a global foreign policy directed at exploiting the United States’ retreats, mistakes or vacuums created by US strategic pull-backs all over the world. Egypt is a particular example. But actually it is only one example in a wider pattern of Russia seeking to exploit US miscues in the Middle East. A particularly strong tool Moscow has wielded to achieve these goals has been arms sales. Though it must be noted that, along with the sale of Russian weapons, energy deals have proven similarly important to the country’s policy aims. Consequently, Russia has pursued both of these tactics to boost its influence with Middle Eastern states like Iraq and Syria (see EDM, October 27, 2010; November 15, 2012). Furthermore, Moscow is currently negotiating an energy deal with Iran (see EDM, January 16).

In Egypt, Moscow is working with the local government to carry out a project by which Russia would supply the Middle Eastern country with liquefied natural gas (LNG). Russia may also advance toward creating a nuclear power plant for Egypt as well (Interfax, March 26). Indeed, some Russian commentators argue that Moscow is at least one step ahead of Washington in creating partnerships, if not outright military alliances, in the Middle East (Izvestiya Online, March 26). The mounting discussions about Egyptian arms sales, first mentioned in 2013, is a sign of this larger process. Nor is Egypt alone. Indeed, Russian officials claim that after Southeast Asia, the Middle East is the second largest market for Russian arms (Interfax, May 6). For example, Russia is also negotiating with Jordan to sell it grenade launchers, mortars and possibly air defense systems (Interfax-AVN Online, May 6). And Moscow is moving forward with new arms sales to Iraq as well (Interfax, May 6).

Egypt wants to purchase Russian MiG-29 fighters, surface-to-air missiles (specifically the S-300, S-400 and Buk-M3 systems), Mi-35 helicopters, coastal anti-ship systems as well as munitions (Interfax, May 6). But Moscow is seeking to activate these discussions with Cairo to regain the level of arms sales that prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s—a period when such Russian arms deals greatly facilitated the Middle East’s slide into endless wars, which has characterized the region ever since. Likewise, Moscow is again prepared to compete with Washington by training Egyptian officers at Russian military academies, as was the norm during the mid-20th century. Indeed, Moscow also seeks to expand cooperation between the two states’ intelligence services (Izvestiya Online, April 29). Given the scope of these bilateral agreements and of Russian ambition, the projected deals represent some new departures in Russian foreign arms sales. For one thing, the Mi-35 helicopter surpasses earlier Russian models to the extent that it has not even entered domestic production yet, showing Moscow’s willingness to sell its most advanced weaponry to some foreign buyers. Additionally, the arms deal will involve not just purchase of the planes but of maintenance, training and logistics systems. In other words it is the wedge behind which a major Russian military presence can then come into Egypt, laying a foundation for longer-term basing rights (Tel-Aviv Institute for National Security Studies, May 1).

As in Egypt, similar arms sales deliberations across the Middle East also reflect major political considerations for Moscow. Recently, high-ranking Russian officials held talks with Qatari, Bahraini and Jordanian officials about not only selling them arms but about improving overall bilateral ties with each of these states. This diplomatic push was clearly part of the broader Russian campaign to gain sway in the Middle East as US influence there recedes (al-Quds al-Arabi, May 14; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, May 6). To the extent that these Russian arms deals go through, bringing with them a concomitant increase in Moscow’s political influence across the region, they cannot but reduce Washington’s leverage upon the recipients. Finally, these efforts add to the perception that Russia is back as a major Middle Eastern player and that the United States is gradually surrendering the field.

If the above-cited deals are taken in tandem with the earlier announcements concerning arms sales to Iraq, energy agreements with Iran, and the expansion of the Blue Stream gas pipeline to Turkey (RIA Novosti, April 21), it should become clear that a comprehensive Russian “military-economic-political” offensive is underway in the Middle East to replace a faltering US. Washington can pretend all it likes that, despite the Ukraine crisis, Russia is a spent force and power, which is in terminal decline given its enormous domestic problems. And perhaps that is the case. But Moscow has not received that memo yet and is thus acting vigorously in the Middle East, Latin America (see EDM, May 2) and East Asia (see EDM, May 7), even as it incites further destabilization across the Middle Eastern region.