Japan Represents Another Russian Failure in Asia

Japan Represents Another Russian Failure in Asia

Although analysts in Russia, no doubt with official prompting, generally talk up the success of their country’s so-called pivot to Asia, in fact that policy has little to show for it after a decade of effort. Today, Russia is clearly dependent on China to an ever-greater degree, including with regard to the Korean issue (see EDM, May 14, 2018; October 23, 2018; March 11, 2019); while the other regional players have clearly marginalized Moscow, as many Russian scholars have had to concede. Meanwhile, with regard to Japan, Russia is now squandering its chances of resolving the 70-plus-year bilateral dispute over the South Kurile Islands and finally signing a post–World War II peace treaty. This failure at a breakthrough with Japan—though it is already being blamed on Japan in the expert literature (Far Eastern Affairs, Russian Academy of Sciences, No. 1, 2019)— lies wholly at Russia’s door.

By late 2018, it appeared that Tokyo was ready to reach an agreement with Moscow strictly on the return of the two smaller of the disputed Kurile Islands to Japan in return for substantial economic benefits to Russia (see EDM, November 27, 2018). However, the negotiating record strongly suggests that Moscow—sensing weakness on Tokyo’s part, probably due to the latter’s hesitant implementation of anti-Russian sanctions, unwillingness to cut off talks, and visible alarm over Beijing’s aggressive policies—decided to ratchet up its demands and force Japan into submission (see EDM, January 24, 2019). Rather than accept a peace treaty on the basis of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 proposal, which Japan itself was prepared to agree to, Moscow now insisted that further dialogue with Tokyo was possible only if Japan unconditionally accepted that Russia had conquered the South Kurile Islands in World War II and would not be returning them (Interfax, February 4).

In adopting this obdurate stance, the Russian government may have been heeding the demands of the military leadership, which has always staunchly opposed ceding any of the Kurile Islands to Japan. Indeed, suddenly, the Russian Armed Forces declared that, for even the two smaller islands to be returned, Japan had to pledge that the United States would never be allowed to set up military bases on them (Mil.ru, December 13, 2018). Far from being content with a clear diplomatic win, Russia thus sought to additionally undermine the US-Japanese alliance. It is worth noting that, as then–Russian Defense Minister Igor Rodionov himself admitted in the 1990s, the US-Japanese alliance has actually prevented an independent Japanese military policy and kept China in check—two vital interests for Moscow (Oles M. Smolansky, “Russia and the Asia-Pacific Region: Policies and Po-lemics,” Imperial Decline, 1997).

And yet, beginning in 2018 and continuing up to the present, Russia has continually attacked Japan for allegedly being subservient to the US. In particular, the Russian government singled out the Japanese decision to deploy the land-based Aegis Ashore missile defense system as well as the earlier decision to host the Terminal High-Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system. Foreign Minister Lavrov recently complained in a television interview that Tokyo “gives the US the right to deploy its armed forces anywhere in Japan, and they [the US] are already deploying their missile defense system there, which creates risks for both Russia and China.” Lavrov continued, “It would be a mistake to ignore the fact that, contrary to the declared goal, this actually worsens the quality of our relations [with Japan].” (Mid.ru, February 24, 2019). As such, he went on to say, under current conditions there was no basis for the Japanese government to believe that an agreement could be reached soon.

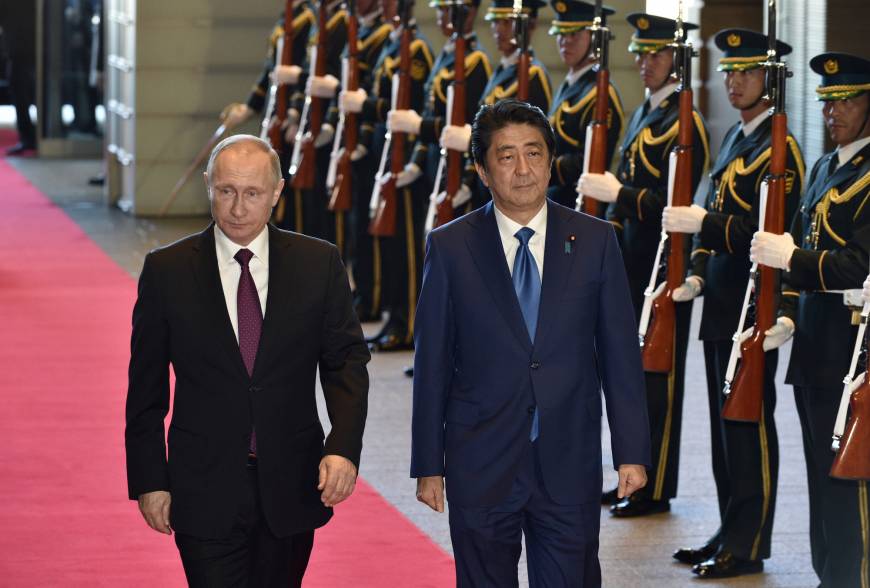

While apparently taking into account the Russian military’s steadfast refusal to concede the southern Kuriles, the government in Moscow may also have hardened its negotiating position based on growing public opposition to giving up any territory to Japan. Indeed, in a January poll, 77 percent of Russian respondents opposed retrocession of the two southernmost Kurile Islands back to Japan (The Moscow Times, January 28). Of course, given President Vladimir Putin’s mastery over Russia—his falling poll numbers notwithstanding (see EDM, March 18)—it is not altogether clear to what degree that recent survey can be assumed to represent the spontaneous expression of public will or whether it was actively manipulated by the Kremlin to undermine the negotiations with Japan. In any case, clearly the authorities made no effort to inform the public before word of this territorial “concession” to Japan leaked out (Vedomosti, January 22); so again the Russian government was culpable.

Following high hopes last year of finally achieving a peace treaty, and after those hopes were again dashed in recent months, Russia has now conclusively announced that the South Kuriles will not, in fact be transferred back to Japan (TASS, March 12). That declaration marks the final failure of the past seven years of negotiations, in which Russia had stood to gain a great deal. As a result, Russia can, at best, expect only marginal economic gains from any ongoing talks with Japan, while any prospect of a “pivot” to Tokyo is now also out of the question. This does not seem to bother Moscow much given Russian disdain for Japan, which it is unwilling to treat as a fully independent power (see EDM, October 9, 2015). But the truth actually is exactly the opposite.

In fact, Russia needs Japanese economic assistance and technology, not to mention political support, far more than Japan needs anything Russia has to offer. And whatever Russia has to offer Japan—including oil or natural gas—is, in fact, a wasting asset. While Japan does not benefit from the impending collapse of this bilateral peace process, it loses nothing that has not already been lost. Whereas, for Russia, the losses—even if is blind to them—are incalculable. Once again, Moscow’s pivot to Asia is proving to be little more than a slide into dependence on Beijing, which, one can assume, is likely pleased at these developments.