Kremlin Gives Go-Ahead to Referendums in Eastern Ukraine

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 87

By:

For all their lack of capacity (let alone legitimacy) to organize any kind of voting, pro-Russia forces in Ukraine’s Donbas are proceeding with secession referendums in the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces on May 11 as scheduled.

Russian President Vladimir Putin had, on May 7, offered to have those referendums “postponed,” ostensibly to allow Ukraine’s presidential election to be held on May 25 country-wide, including the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. That offer’s first recipient, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), looked pleased (see EDM, May 8).

Nevertheless, on May 8, Russia’s state television channels publicized the two “referendums,” due on May 11, and featured interviews with secessionist leaders announcing that the “voting” would proceed as scheduled. Russia’s television channels pointedly referenced the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and the “Luhansk People’s Republic” (Russian TV Channel One, TV Rossiya TV, NTV, May 8).

Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov made clear that Putin’ offer to postpone the referendums had been a conditional one. Peskov declared that the decision is up to “people’s congresses” in Donetsk and Luhansk, depending on whether Kyiv withdraws its troops from Ukraine’s east and starts negotiations with “representatives of these regions” (RIA Novosti, May 8). In Moscow’s recent parlance, “representatives of [Ukraine’s] eastern and southern regions” is a designation that extends from “federalizers” to separatists.

All this emboldened the secessionist groups, dispelling any doubts that may have ensued from Putin’s May 7 statement. The Kremlin’s televised message told the secessionists, directly, to go ahead with the referendums, and indirectly, that Putin’s statement was only intended for Western consumption, not an instruction to his forces in the field.

On May 6, Russia’s Duma had declined to send observers to the referendums, on the grounds that “this is an internal matter for the Donetsk and Luhansk regions” (Interfax, May 6). This argument may presage a decision to treat the “referendums’ ” outcome as valid.

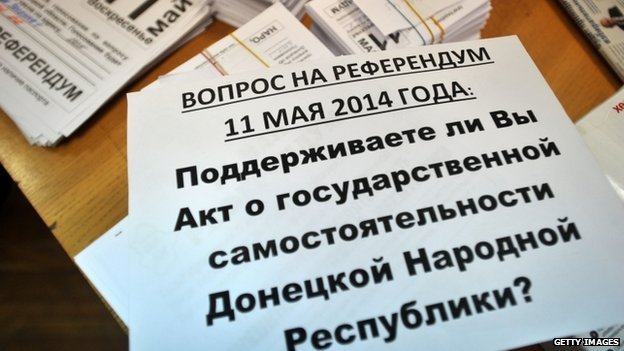

The referendums feature a single question on the ballot, with no alternative options, and formulated identically in both cases: “Do you support the act of the state independence of the Donetsk People’s Republic / Luhansk People’s Republic?” The key term in Russian is “gosudarstvennaya samostoyatelnost,” which falls somewhat short of outright independence, but can be interpreted as a mandate for full secession. This remaining ambiguity is designed to provide Russia—and the pro-Russia “representatives of these regions”—with leverage against Ukraine in subsequent negotiations.

Leaders of the “Donetsk People’s Republic’s presidium” (Denis Pushilin) and that “republic’s government” (Myroslav Rudenko) announced through the Moscow mass media on May 8 that the referendum would go ahead as scheduled on May 11, by decision of the groups they represent. From Luhansk, an identical decision was announced by the “press service” of the “headquarters of the ‘Army of the South-East’ ” and the “people’s governor” Valery Bolotov. His counterpart in Donetsk, “people’s governor” Pavel Gubarev (Pavlo Hubaryov), has just been released from detention by Kyiv in return for three SBU officers released by rebels from Slovyansk (Interfax, RIA Novosti, May 8).

Russia’s state television channels had started featuring those groups and their representatives occasionally during April, so as to acquaint Russian and eastern Ukrainian audiences with this new brand of secessionists. Those groups and like-minded ones have joined under the umbrella of the “South-East Movement for Federalization [of Ukraine],” chaired by Oleh Tsaryov. The latter urged proceeding with the referendums “with all due respect and affection for Putin” (Pdrobnosti, May 7). A member of Ukraine’s parliament from the Party of Regions, Tsaryov espouses pan-Russian views far out of character with that party.

All those “people’s councils,” “people’s governors” and associated “people’s mayors” are utterly marginal figures. They claimed those titles during pro-Russia rallies that resulted in the capture of administrative buildings in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces starting from April 6.

These groups are insurgent against the Ukrainian government and the state as such, but equally against the Party of Regions, which remains the main political force in this part of Ukraine. The new generation of younger, dynamic, Greater Russia–minded activists, pressing for Ukraine’s “federalization” or secession from Ukraine, aim by the same token to supplant the Party of Regions’ nomenklatura. The latter generally opposes Ukraine’s “federalization.” The Kremlin is using the new brand of pro-Russia activists to displace the Party of Regions from its entrenched positions. Moscow’s regime-change policy is two-pronged, targeting both Kyiv and Donbas (Donetsk and Luhansk provinces).

On April 25 in Donetsk province and on May 5 in Luhansk province, the “people’s councils” and “people’s governors” decided to hold the referendums on May 11. As of now, they lack a social, electoral, or organizational base for holding anything resembling referendums or elections. Their paramilitary units have failed to establish any compact territorial base for such an undertaking. They only hold some dots on the map. Those dots are not even towns (not even in Slovyansk), but some administrative and police buildings in town squares. They can announce any result that they see fit from the “referendums,” or that Moscow will see fit to use against Ukraine.