Kyrgyzstan Looking to China for Strategic Investments

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 131

By:

As a small, poor and isolated country, Kyrgyzstan, does not have the luxury of picking its foreign partners. While its leadership continues to look north to Kazakhstan and Russia in determining its geopolitical orientation, and to the West for some semblance of democratic self-affirmation, it increasingly turns to China for pragmatic economic cooperation, investment and financial aid.

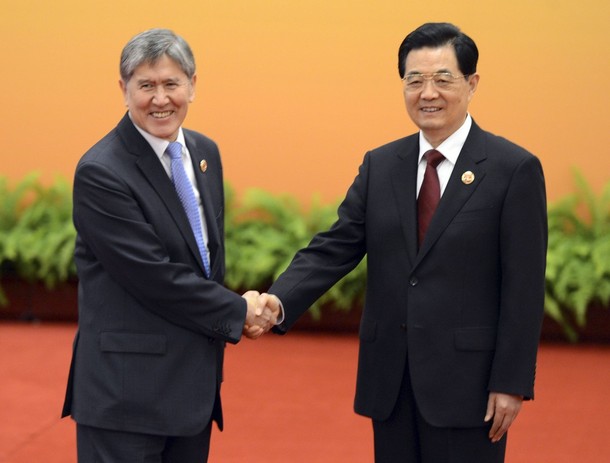

Kyrgyzstan’s President Almaz Atambayev paid a state visit to China in June, precipitating a series of public statements on policy toward Beijing, and a number of agreements that illustrate the increasing interest of the Kyrgyzstani leadership in cooperating with China.

After Atambayev signed a preliminary agreement in China, Kyrgyzstan’s parliament approved on June 14 a $389 million soft loan deal with China’s Export-Import Bank, whereby the latter will build a south-north electricity line and improve related infrastructure. At two percent interest for nine years, the loan is likely larger and cheaper than one that might be offered by Western- or Russian-backed development banks (K-News, June 14).

The project is meaningful for Kyrgyzstan, as it will allow the country to transit electricity from its main hydropower station in southern Jalalabad through its own territory to Bishkek and the surrounding northern regions. Currently, Kyrgyzstan relies on transit agreements with Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to power its north, as was intended for the Soviet-era regional energy grid. Regular accusations of electricity siphoning have brought the sharing system to near collapse in recent years and threaten to leave Bishkek and northern Kyrgyzstan with severe power deficits in summer. China’s interest in the project stems from the potential to import Kyrgyzstan-origin hydropower during the summer season via the new lines (FerganaNews, June 14).

Both sides expressed support for a curious private Chinese investment in a small oil refinery in the northern Kyrgyzstani town of Kara-Balta, along with a minor oil pipeline from the nearby city of Shymkent to supply the facility. Even at full capacity, the facility will supply only 65 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s demand for refined fuel products. However, the refinery will be the country’s largest, and will exist in isolation in a market increasingly dominated by Gazprom.

Later, back in Kyrgyzstan, the PLA’s Deputy General Chief of Staff Ma Syatoyana met with Atambayev, where the latter issued the now-famous Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s boilerplate statement on their shared threats of separatism, extremism and terrorism (Erkin-Too, via www.gezitter.org, June 19).

Later, a cultural delegation discussed China’s increasing interest in social ties. Confucian Centers sponsored by the Chinese government are teaching Mandarin to middle-class Kyrgyz at several Bishkek universities. A Kyrgyzstani vice premier even proposed establishing a Chinese university in the northern town of Tokmok (K-News, June 27).

The leadership’s desires to build ties with China are understandable. While China’s practice of offering investment on a quid pro quo basis is often viewed with suspicion or derision by Russia and the West, Chinese terms are generally more favorable than those offered by the former. Kyrgyzstan is now considering Chinese investment in a massive hydroelectric project that Russia has dallied on for years. China’s demand for energy imports may make it a more natural partner. Yet, considering Kyrgyzstan’s economic stagnation and record of expropriations, Russia has good reason to remain circumspect.

Russia’s more recent tendency to demand assets, such as the Dastan torpedo factor or KyrgyzGaz distribution network, in exchange for loan forgiveness can be nothing but worrying for officials in Bishkek. Handing over state assets such as these, even unprofitable ones, can mean significant losses of revenue streams for government patrons and allies.

And while Western companies may offer the best technology to exploit the country’s mineral resources, the Kyrgyzstani parliament’s most recent flirtation with nationalization of the Canadian-owned Kumtor Operating Company has sent yet another warning shot across the bow of foreign investors from further afield.

Chinese terms become still more favorable considering the lack of transparency inherent in China’s soft loan and concessionary infrastructure deals. Compared to the auditing requirements and performance targets required for financial assistance by Western governments and development banks, the opaque deals with Chinese government agencies are more profitable for officials on both sides of the signature page, regardless of the underlying investment.

Such dealings with China do not come without political risks for Kyrgyzstan’s leadership. One article in the Kyrgyz-language press decried the “millions” of Chinese immigrants that would enter the country with the construction project, and described Atambayev as having set Kyrgyzstan on course to becoming the “Chinese-Kyrgyz Republic” (Zhany Ordo, via www.gezitter.org, June 29). Meanwhile, a youth movement is petitioning to put the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway project to a popular referendum (K-News, June 15). Animosity toward China is pervasive among Kyrgyzstanis across ethnic groups, owing to Soviet-era prejudices and to the Kyrgyz fears of lacking sovereign control of their own destiny. Nationalist opposition politicians have been quick to capitalize on the government’s carousing with China.

The Kremlin has allowed Kyrgyzstan to court China, but its Customs Union project and its insistence that Kyrgyzstan sign on may ultimately limit China’s economic interests in the country.

In the interim, while the Kyrgyzstani leadership approaches China as a natural economic partner, it will continue to raise the risk of instigating its restive streets. Whether Atambayev and his ally, Prime Minister Omurbek Babanov, can manage to attract significant Chinese resources without risking their own power – either to foreign intrigues or domestic unrest – will likely be the principle foreign policy question of their reign.