Mauritania Confronts Structural Problems as It Steps Up Counterterrorism Efforts

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 31

By:

The past six weeks have seen an escalation of hostilities between Mauritanian troops and the forces of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). The first signs of this escalation occurred on June 24, when Mauritanian forces raided, with Malian help, an al-Qaeda camp in the Wagadou forest in Northeastern Mali, killing fifteen militants (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, July 7). Unlike its sanctuaries in the remote desert of Mali and Algeria, AQIM’s decision to establish a forward operating base (a mere 70 km away from Mauritania) was a bold move that put the group within striking distance of Mauritania’s urban centers (Jeune Afrique, July 6). The make-up of the AQIM contingent (half of its members were Mauritanians) also raised alarms in Mauritanian circles, as it confirmed accounts of the rising number of Mauritanians in AQIM. Mauritania’s military operation in Mali was therefore necessary to signal resolve and demonstrate an ability to dismantle sanctuaries from which the country can be attacked. However, shortly after the Mauritanian operation, another heavy-armed confrontation broke out on July 5 when scores of AQIM fighters attacked an army base in the eastern Mauritanian town of Bassiknou, near the troubled border with Mali (Agence Nouakchott d’Information, July 5). This was a retaliatory strike intended to show the versatility of AQIM and its continuing ability to mount attacks inside Mauritania.

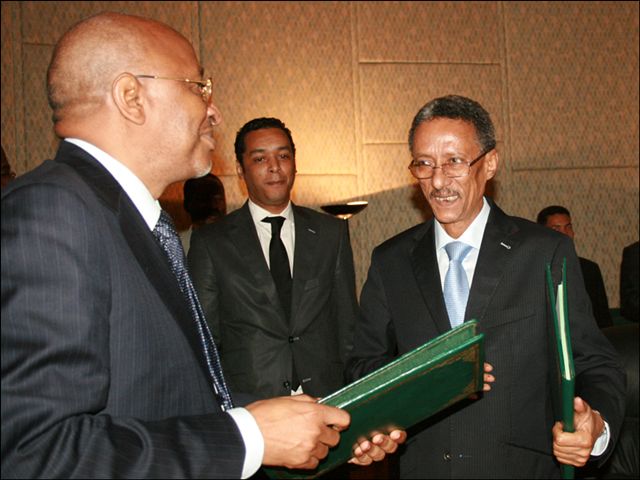

These fierce battles have been closely watched by political and military leaders in the fragile Sahelian states most threatened by AQIM’s destabilizing activities and their backers in the West. The latter, especially the United States and France, are eager to see how effective their investments have been in boosting the military capabilities and counterterrorist cooperation of their African allies. The military encounters also provided an opportunity to observe AQIM’s capabilities and how they were affected by the group’s alleged supply of weapons smuggled from Libya (Jeune Afrique, March 25). The performance of the Mauritanian forces and the cooperation of Mali must have been a welcome development, as was clearly expressed in Nouakchott by the head of the United States African Command (AFRICOM), General Carter Ham. “I congratulated [the Mauritanian president] for the success of the Mauritanian army in its fight against AQIM, in collaboration with Mali and other countries in the region,” said Ham after a meeting with President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz (AFP, July 12). French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé, also on a visit to Mauritania, praised the country’s “exemplary fight” and stressed the need for other countries to stay “more engaged” (AP, July 11). This was a veiled reference to Mali, which has long been seen as a lukewarm partner in the war on AQIM, preferring to maintain neutrality in a fight some Malians consider not their own.

Mauritania, by contrast, emerged as one of the nations most determined to strike at AQIM within and beyond its territory. This aggressive counterterrorism campaign finds its roots in the massacre perpetrated by AQIM in September 2008, shortly after the coup that brought Abdel Aziz to power, when 11 Mauritanian soldiers and one civilian were captured and decapitated outside of Tourine in an attack claimed by AQIM (Akhbarmauritania.info, September 18, 2008; al-Fajr Media Center, September 23; see also Terrorism Focus Brief, October 1, 2008). Since then, Abdel Aziz has taken the offensive against units of AQIM led by Yahya Abu Hamam, an Algerian tasked with mounting terrorist operations against Mauritania (Jeune Afrique, July 6). Obviously, Mauritania’s struggle with terrorism predates the 2008 attacks. The terrorist threat first emerged in earnest in 2005 with the deadly attack perpetrated by the GSPC against the Lemgheity barracks, killing 15 Mauritanian soldiers (El-Watan [Algiers], July 6, 2005; al-Jazeera, June 5, 2005). More worrisome for Mauritania and its Western allies has been the ability of the terror network to make recruiting inroads in the country.

The recruits share the same difficult background. They are young, hail from the poor neighborhoods on the periphery of Nouakchott and possess little education. [1] This profile has reignited the debate about the drivers of extremism and terrorism. As many authoritative studies have shown, socio-economic deprivations do play a role in radicalization, but they do so indirectly and often in conjunction with other “causal factors.” In the case of Mauritania, it is chronic weak governance, extreme inequalities and structural social injustice that enable violent extremism. Rapid urbanization of society has aggravated social tensions in the country by weakening traditional mechanisms of social regulation. A USAID report on Mauritania clearly documents a trend whereby the vulnerability of youth to extremism “increases where family, clan and ethnic-based structures that used to constrain anti-social or violent behavior have frayed or disappeared, where the state has shown itself unable to create alternative mechanisms of social regulation, and where former avenues of sociability have faded away.” (2) It is within this context that radical Salafist ideas thrive. Salafi-Jihadi groups in internet forums, mosques, and prisons have taken full advantage of the dissolution of these societal controls and the pervasive marginality of significant numbers of youths to lure them into extremist groups.

The Mauritanian government has undertaken several steps and initiatives to combat extremism. In addition to improving its fighting capability and modernizing its military equipment through the acquisition of high-performance aircraft and other materiel, the government has bolstered its legal system. New anti-terrorism legislation tries to balance security and legality, as establishing the legitimacy of counterterrorism laws is essential to gaining popular support for prosecuting the country’s war on extremism and terrorism. The government has also tried to delegitimize the ideological justifications for radicalism by hiring hundreds of new imams to preach in the country’s mosques as well as engage extremist prisoners through a dialogue with state-sponsored Islamist scholars and clerics. (3) The goal is to rehabilitate violent extremists as well as to demobilize and de-radicalize potential recruits.

Notes:

1. Alain Antil and Sylvain Touati, ?Mali et Mauritanie: pays sahéliens fragiles et états résilients," Politique Etrangère 76(1), Spring 2011, pp.59-69.

2. Guilan Denoeux, “Guide to the Drivers of Violent Extremism,” USAID, February, 2009.

3. Cédric Jourde, “Mauritania 2010: between individual willpower and institutional inertia,” IPRIS Maghreb Review, March 2011, pp. 1-6. See also Terrorism Monitor Brief, February 4, 2010.