Mekong Murders Spur Beijing to Push New Security Cooperation

Publication: China Brief Volume: 11 Issue: 21

By:

On November 1, Chinese security officials and their counterparts from Burma, Laos and Thailand announced a new security initiative to make the Mekong River safe for commerce as it passes through the volatile “Golden Triangle.” The four parties issued a joint statement indicating they will step up law enforcement patrols and create a new cooperative mechanism for sharing intelligence, joint operations and shared emergency response (People’s Daily, November 1; Xinhua, November 1). The announcement capped a hectic month of debate and diplomacy in China following the murder of 13 Chinese boatmen in northern Thailand on October 5—now referred to as the “10-5 Incident” in Chinese press (Guangming Daily, October 10; Xinhua, October 10).

In early October, drug traffickers hijacked two Chinese riverboats to use in transporting narcotics and murdered the 13 crewmen. The attacks left 164 boatmen and 26 boats stranded in Thailand after shipping was suspended along the Mekong (Xinhua, October 10). China sent police escort vessels to bring the stranded boatmen and boats home in two groups, which returned to Yunnan on October 16 and October 23 (Xinhua, October 23; October 16).

The hijacking and murders spurred discussion in China about the security of Chinese citizens abroad and Beijing’s responsibilities. Wang Hanling said Beijing should recognize protecting Chinese citizens abroad is going to become a bigger challenge (Guangzhou Daily, October 12). Taking a different tack, Zhu Feng, Deputy Director of Beijing University’s Center for International and Strategic Studies, raised the question as why do China’s neighbors choose to neglect its interests. Zhu posited China’s Mekong neighbors would not respect Chinese interests routinely until Beijing started to provide essential public goods, such as taking the lead on regional governance (Firstpost [India], November 1).

On the policy front, Chinese experts and officials, as well as their Southeast Asian counterparts, started making noises about new security cooperation. Official press stated the Mekong River in the Golden Triangle is becoming more and more like the Gulf of Aden—an important waterway increasingly threatened by pirates. China has two options to consider: Gulf of Aden-like deployments and a new regional security cooperation mechanism (People’s Daily, October 24, October 18; Xinhua, October 14). China Academy of Social Sciences expert Jia Duqiang noted, while there is no short-term fix for problems in the Golden Triangle, Beijing had an opportunity to take a more positive role in building cross-border cooperation mechanisms (Guangzhou Daily, October 12). Bangkok and Vientiane both opened the door to consider new Mekong security cooperation and Thailand boosted its patrols along the river (China News Service, October 14).

Beijing‘s response to the “10-5 Incident” developed rapidly, led by State Councilor and Minister for Public Security Meng Jianzhu. Beijing directed the Embassy in Bangkok and the Consulate in Chiang Mai to press Thai authorities to investigate promptly and track down the perpetrators. The relevant Yunnan provincial departments also set up an emergency leading group in conjunction with the Ministry of Transportation and the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) while investigations proceeded (Guangming Daily, October 11). On October 13, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs called in the interim Thai charge d’affaires in Beijing to urge on the Thai investigation and, more importantly, stated China would engage multilaterally to improve security on the Mekong River (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 13). On October 23, Minister Meng chaired a security conference at Xishuangbanna while MPS Vice Minister Zhang Xinfeng led a high-level, eight-man security delegation to assist with the investigation in Thailand (Xinhua, October 26, October 23). The following day, Meng emphasized the importance of the Mekong River in Chinese-Southeast Asian trade and a vital link connecting the region (People’s Daily, October 24).

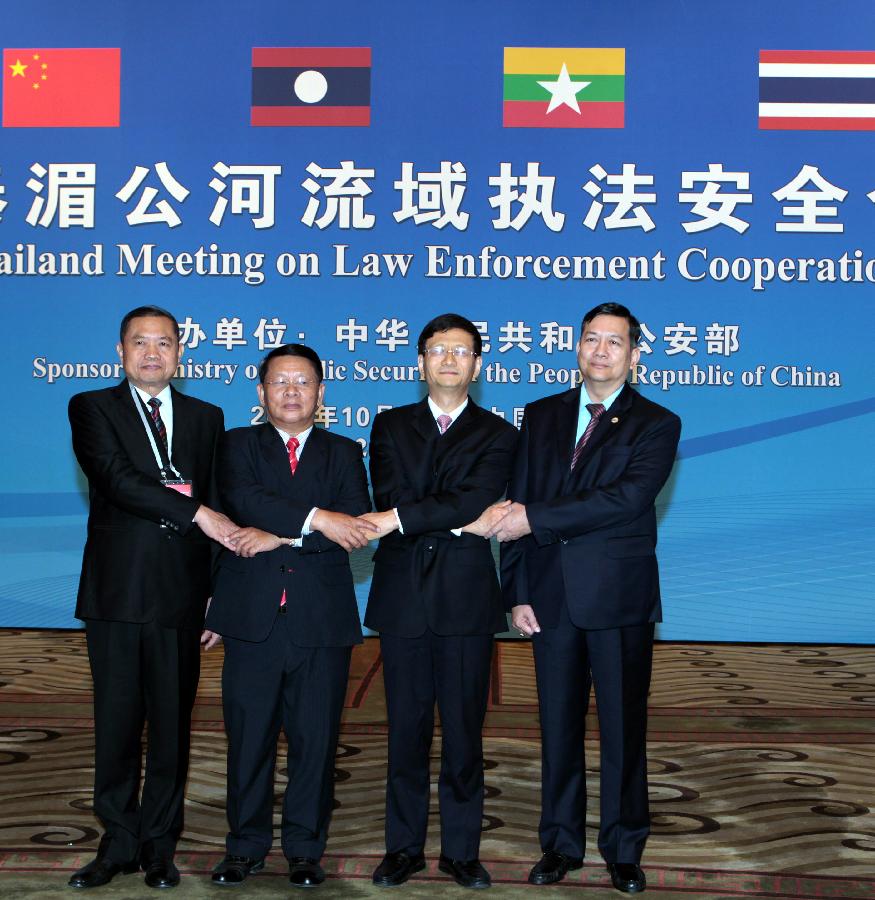

A week later on October 30, Beijing hosted a two-day security conclave at the Diaoyutai Guesthouse with Burmese, Laotian and Thai officials. While Politburo Standing Committee member and Secretary of the Central Political-Legal Committee Zhou Yongkang met individually with the leaders of each foreign delegation, Meng also met each side individually and chaired the conference proceedings going into the next day. At the end, Meng, Thai Deputy Prime Minister Kowit Wattanna, Laotian Minister of Defense Douangchay Phichit and Burmese Minister of Home Affairs Ko Ko announced the formal creation of the “Mechanism for Law Enforcement Cooperation along the Mekong River” (Xinhua, November 1, October 31; China Broadcasting, November 1; China Police Daily, October 31).

The joint statement set the objective of securing the Mekong River for trade by the time of the next Great Mekong Sub-region Meeting in December (Xinhua, November 9). China, Burma, Laos and Thailand will create joint river patrol with China’s contribution probably coming under the jurisdiction of the Xishuangbanna border guard detachment. China may contribute 1000 or more people to the effort, but official press places the number around 600 security personnel, using refitted merchant vessels and speed boats (Phoenix Television, November 7; Xinhua, November 9).

At least one Chinese observer, a professor at China’s Public Security University, advocated caution in greeting the announcement, because the agreement was still only an agreement on paper and dealing with four different legal and political systems presented significant hurdles (Xinhua, November 1). Nevertheless, official press outlets suggested the Chinese seriously are considering armed escort boats for Chinese river traffic and more regularly employing security personnel to protect Chinese businesspeople and traders abroad (Xinhua, November 9; Global Times, November 8). An editorial in one southern Chinese paper stated China should go beyond mechanical adherence to “non-interference in internal affairs” and actively participate in international rule-making. China’s naval support for the anti-piracy in the Gulf of Aden should be used as an exemplar, even if the situation on the Mekong is more complex. The paper opined pushing forward with joint policing of the rivers will be difficult, but “undoubtedly the most direct and effective” way to protect Chinese and international interests (Southern Metropolis Daily, November 6).

Regardless of how well action matches rhetoric, the remarkable thing is how fast Beijing moved on a transnational issue involving sovereignty and potentially the use of force—albeit against non-state groups—beyond China’s borders. As one Ministry of State Security researcher put it, this Mekong River agreement is a breakthrough (China Daily, November 1). This agreement, especially if Chinese border guards regularly patrol the river beyond China’s border, suggests a changing Chinese security consciousness that recognizes Beijing must be much more involved beyond its borders to preserve and protect its interests.