Moscow Learns to Play by Asia-Pacific Rules

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 31

By:

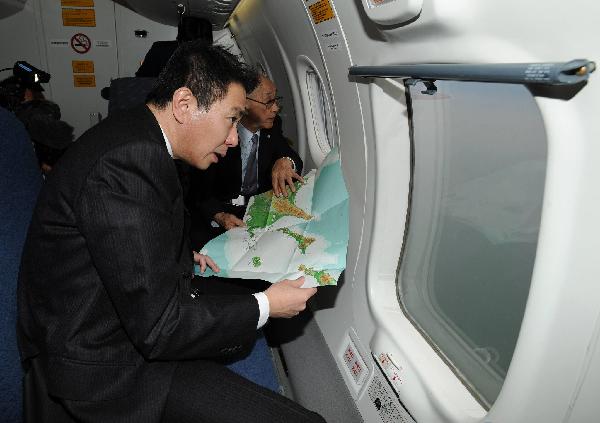

The visit to Moscow by Japan’s Foreign Minister, Seiji Maehara, on February 11 did not lessen the diplomatic row between Russia and Japan that acquired a spectacular character during the last two weeks (RIA Novosti, Kommersant, February 12). The Kremlin appeared prepared rather than perplexed by Japan’s Prime Minister, Naomo Kan’s, characterization of Russian, President Dmitry Medvedev’s, visit to the Southern Kurile Islands as an “unforgivable outrage” and advised him “to prepare for a tough time ahead” (Rossiyskaya Gazeta, February 8). This advice was elaborated in Medvedev’s order to Defense Minister, Anatoliy Serdyukov, who had inspected the troops on the disputed islands one week prior to deploying additional modern weapons there “to ensure the security of these islands as an integral part of the Russian Federation” (Vedomosti, February 10). Medvedev also insisted on additional funding for improving infrastructure on the Kuriles in order to develop tourism and increase their “investment appeal.”

The quarrel might appear as senseless as the proposition that investors who moved some $30 billion out of Russia last year would flock to the remote islands, where the main activity has always been supporting the needs of the 18th Machine-Gun-Artillery Division, which has shrunk to less than one third of its Soviet era strength of 10,000 soldiers (Kommersant, February 11; www.gazeta.ru, February 8). Making the high-profile visit to the Kuriles Medvedev took a few photos against the background of the rusty tanks of this division, which indeed needs some new guns to replace its totally dilapidated arsenal, but it probably needs downsizing to brigade level more than any other unit in the Russian army that is undergoing painful and poorly planned reforms (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, February 11). The dispute with Japan about the ownership of three mid-sized islands (Iturup, Kunashir, Shikotan) and a group of islets (Habomai) dates from the outcome of World War II and has seen many twists and turns, including Khrushchev’s suggestion to split the difference and sign the long-delayed peace treaty (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, February 10).

Medvedev’s eagerness to escalate the quarrel appears out of character and invites the question about its political rationale. Domestic electoral maneuvering –also very prominent in Japan– is the easily available explanation, and asserting sovereign rights over a piece of land, however insignificant and inhospitable, are indeed a faultless method for boosting patriotic feelings (Novaya Gazeta, February 8). Medvedev, however, can hardly count on scoring points with the conservative-nationalist camp where he is perceived as a featherweight weakling but needs support from the wavering groups of “modernizers” who see the spat with Japan as senseless and unhelpful. Medvedev’s popularity is in decline, but in striking the pose of a resolute leader he invariably takes a scratching false note (www.gazeta.ru, February 10).

The rationale behind the conflict-fanning course appears more solid in the context of Russia’s efforts to strengthen its profile in the Asia-Pacific region where the notion of “sovereignty” is taken very seriously. The states of the region traditionally declare their devotion to cooperation but pursue their national interests with uncompromising zeal, so that recent clashes on the Thai-Cambodia border or firing on fishermen near a group of disputed islands is the norm rather than a series of exceptions. Russia’s readiness to accommodate Chinese claims for islands on the rivers Amur and Ussuri, including Damansky that saw fierce fighting in 1969, and its withdrawal from the Cam Ranh base in Vietnam reflect rather poorly on its standing in this quarrelsome neighborhood, so Moscow needs to strengthen its hand before hosting the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Vladivostok in 2012. Picking a “fight” with Japan appears to be a safe option since Russia could take for the reference point its prominent role in World War II and not some obscure historical episode (Kommersant, February 11).

Moscow is perhaps slightly upset that the new US Military Strategy mentions Russia in barely two sentences, but it has duly noted that it is exactly its role in the Asia-Pacific that is acknowledged (www.gazeta.ru, February 10). In this context, the plan for deploying the two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships that France agreed to build for Russia to the Pacific Fleet in order to defend the Kuriles appears not that far-fetched, even if the helicopter-carriers are clearly unsuitable for this role (Rossiyskaya Gazeta, February 10).

Adopting an assertive political style Medvedev seems unaware that what suits naturally the emerging Asian powers finding new confidence in their fast growth looks rather awkward for Russia with its economic sluggishness and dwindling population in the Far East. Moscow definitely wants to avoid the role of raw materials supplier to its dynamic neighbors; hence its husbandry of a not small herd of white elephants” –including the gas pipeline from Sakhalin to Vladivostok to the Vostochny space launch site. The sustainability of these grossly cost-inefficient projects is doubtful, but Moscow still seeks to increase the dependency of these peripheral provinces on funding from the federal budget, stretched as it is, suspecting that local initiatives would free them from central control (www.besttoday.ru, February 12). Japan and China and every other fast-moving economic “dragon” are perfectly aware of the severe stagnation in the Russian Far East and are not very impressed with the zigzags of policy from a position of weakness.

The coherence of Russian foreign policy is certainly undermined by the need to play by one set of rules in the dynamic Asia-Pacific, and by different rules in the conflict-ridden Caucasus that borders the nearly-nuclear Iran, and by a third set of rules in the post-geopolitical Europe, so that the squabble with Japan occurs simultaneously with debates in the State Duma on the ratification of the maritime border treaty with Norway. A greater problem is that in none of its neighborhoods can Russia perform a role that would have answered partners’ expectations and its own ambitions. There is an irreducible weakness at the very center of Russian political decision-making where the ruling duumvirate cannot accept its fundamental inadequacy to the tasks of Russia’s modernization. Foreign policy has become a means to camouflage this inadequacy rather than to resolve these tasks, but such a strategy can only succeed in fooling its authors.