Moscow’s Territorial Division of Central Asia in 1920s ‘Artificial,’ Tajik Historian Says

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 126

By:

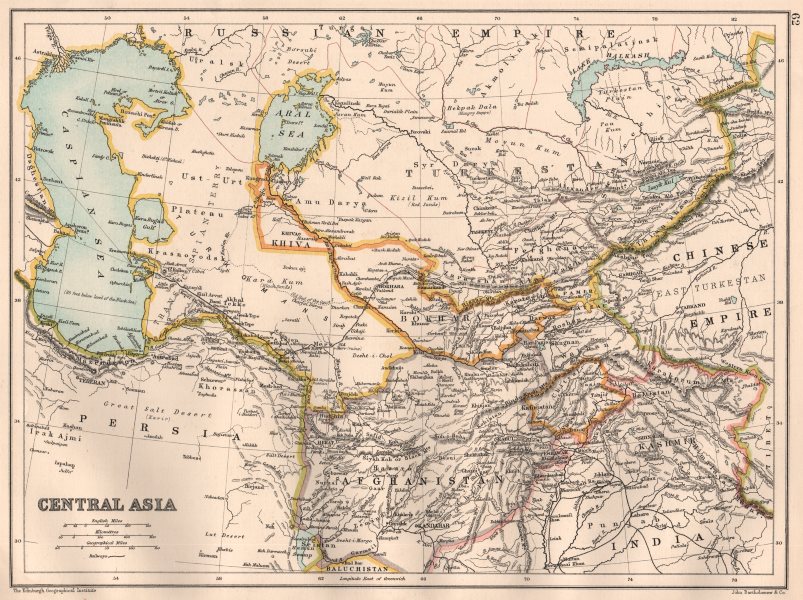

The Bolshevik government achieved two goals by dividing up the territory of Central Asia into various national republics—it undermined the Pan-Turkic aspirations of the jadids, and it helped break the anti-Soviet basmachi movement by refocusing the attention of the local population on national construction, according to Rakhimbek Bobokhonov, a Tajik historian who works at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow.

But if it could be called a success from that point of view, he argues in a new article summarizing his forthcoming book on the subject (Centrasia.ru, July 2), the division of the region—usually referred to as “razmezhevaniye” or “territorial delimitation”—was “an artificial experiment.” Such newly created divisions ignored the psychology and identities of the people there and put in place some delayed-action mines, which are now at risk of exploding under all of the countries that gained their independence in 1991 (Ozodi.org, July 4).

In the course of territorial delimitation, he says, the Tajiks lost their most important historical and cultural centers and saw the destruction of the Sarts who spoke Tajik at home but used a Turkic dialect in public. Because they thought in Tajik, he argues, the Sarts should have been included within the Tajik republic and nation. But because razmezhevaniye was run by Uzbeks and because Moscow was focused on other issues, they were lost to the Tajiks and to history. At the same time, he suggests, the Tajiks can take some comfort in the fact that the act of “razmezhevaniye” in the 1920s set the stage for their emergence as an independent state now.

That is hard for many to accept, he acknowledges, because the Tajiks at the time were major losers as a result of Moscow’s policies. They lost their two most important cultural centers—Bukhara and Samarkand—both of which were handed over to the Uzbeks; and they found themselves in a situation that remains true tiday, in which “the number of Tajiks abroad (those who live in Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Kashgar in China, Pakistan and other parts of the world) exceeds those who live on the territory of Tajikistan” (Ozodi.org, July 4).

In his research, Bobokhonov says, he has devoted particular attention to “the fate of the Sarts because what happened to them is a national tragedy of the Tajik people.” Indeed, he suggests, “the largest victim” of territorial delimitation in Central Asia were the Sarts, who were mistakenly reclassified by the Uzbeks as Uzbeks, and thus lost to the Tajik nation (Ozodi.org, July 4).

The Sarts spoke a Turkic dialect known as Sart Tili, which was sufficiently distinct to classify it as a language. But regardless of the language they spoke in the streets, Bobokhonov says, the Sarts “were Tajiks because they thought in Tajik,” something that Uzbek leader Fayzullo Khodzhayev simply ignored in order to build a larger Uzbek nation and a larger Uzbekistan.

“If the Sarts had been classified as Tajiks at that time,” the Tajik scholar says, “then today we would have a completely different state.” But the Bolsheviks were focused on defeating the basmachi and thus decided, along with Khodzhayev, that “it would be better if they did not give power to the Sarts and Tajiks.”

Bobokhonov’s words show just how sensitive this issue remains. He explicitly casts himself as a dispassionate scholar who wants to avoid any emotionalism. But it is clear from his words that like many other Tajiks, he is offended by what Tashkent and Moscow did almost a century ago. It is evident that Bobokhonov and other modern-day Tajiks view the borders that were laid down in the early 20th century as artificial in a fundamental sense, however much they may be compelled by current circumstances to tolerate them at least for the time being.

According to the Tajik scholar, the Bolsheviks had no choice but to carry out the territorial delimitation of Central Asia because they had promised all nations the right of self-determination. But the actual implementation of that policy, he acknowledges, was selective and was often driven by short-term political needs. Thus, in Central Asia, Moscow was far more concerned about blocking the spread of pan-Turkist and even pan-Islamist ideas and fighting the basmachi than in coming up with borders that reflected the actual ethnic patterns in the region.

In both of these things, he suggests, Moscow was remarkably successful. Local people focused on the construction of national republics, including the demarcation of borders, and increasingly ignored the appeals of the two groups that the Bolsheviks hoped to defeat. It is thus not unreasonable to say that razmezhevaniye played a key role in defeating the basmachi and solidifying Moscow’s control over the region.

But perhaps the most important aspect of Bobokhonov’s research for those analyzing Central Asia today is the attention he gives to other forms of Moscow’s divide-and-rule policy there, including not just games with ethnic identity, as in the case of the Sarts, but also drawing borders and promoting linguistic divisions to create tensions among the various nations of the region and playing off water surplus against water shortage republics. Those actions, he makes clear, are continuing to play out in post-Soviet Central Asia, a kind of poison pill inserted by the Bolsheviks whose impact in the absence of a single arbiter is becoming ever greater.