MSS Sensationalizes National Security Awareness

Executive Summary:

- Online messaging campaigns from the Ministry of State Security (MSS) seek to educate citizens about national security threats and to instill a suspicion of foreigners, especially those from West countries.

- Numerous examples in WeChat posts from 2025 detail ways in which foreign spies might manipulate people into providing sensitive information and describe how model citizens can report suspicious activity to the authorities.

- The 2023 decision by the MSS to raise its public profile via social media echoes an approach taken by other international security services in recent years. The ministry hopes to professionalize its image, shedding its reputation as an opaque organization and building legitimacy for its mission to protect citizens from foreign threats.

The Ministry of State Security (MSS; 国家安全部) WeChat account has, for over two years, been a key part of its public education effort (China Brief, September 22, 2023). In 2025, posts have warned against a range of national security threats. Examples include foreign entities luring college students into filming military airports and tricking people into remote part-time jobs that are actually vectors for military espionage, cognitive operations involving card games with “problematic maps” (问题地图), and even smart TVs broadcasting illegal content. The increasingly broad nature of threats featured across its 269 posts, as well as the frequency of messages, indicates that the MSS recognizes a growing number of domains in which foreign intelligence organizations may seek to exploit people within the People’s Republic of China (PRC). [1]

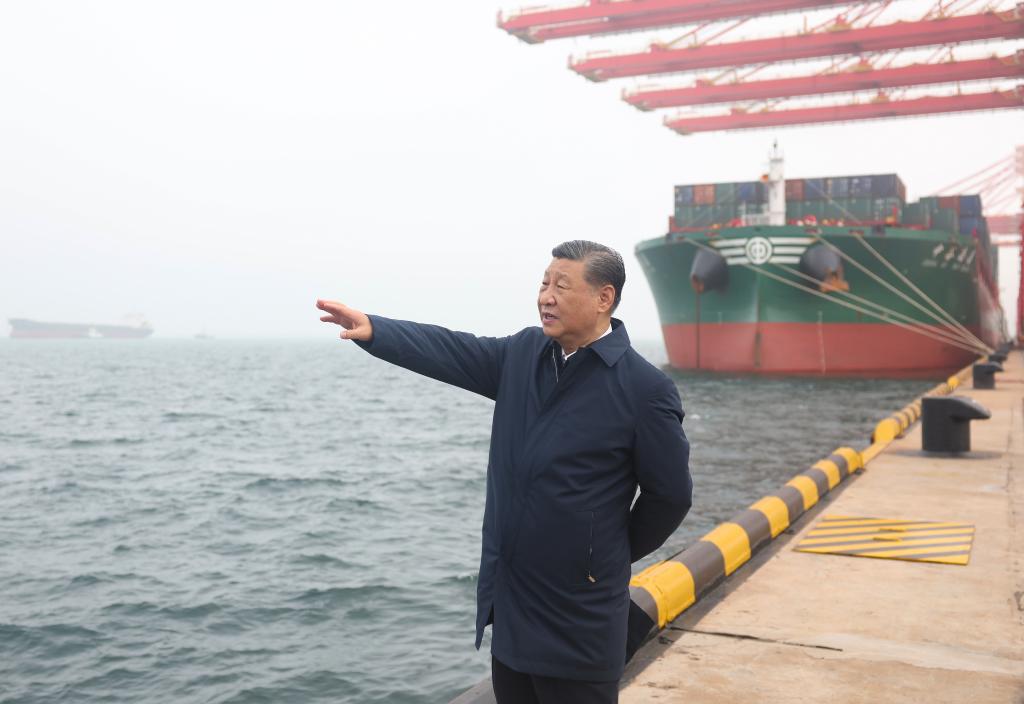

The constant communications emphasize that the political security of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the foundation for the entire national edifice, and are downstream of the implementation of CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s “comprehensive national security concept” (总体国家安全观) (China Brief, April 26, 2024). The MSS WeChat posts receive widespread coverage in Chinese news media. This is likely part of a coordinated approach to online messaging that maximizes impact across platforms, as observed in other PRC influence operations (China Brief, July 25). The sensationalist manner of the posts is designed to shock citizens into believing that they face a constant threat from “foreign hostile forces” (境外敵對勢力). It also seeks to involve them in national security work, expanding threat dissemination beyond the traditional audience of Party cadres and government officials to the whole of society. Part of this is done by encouraging vigilance and actively reporting suspicious activity directly to the MSS.

Most ordinary PRC Chinese citizens have historically had little knowledge of how the MSS operates, instead harboring a healthy dose of fear and apprehension about the formidable security apparatus. Echoing an approach taken from security services internationally in recent years, the ministry is engaging more on social media in an effort to professionalize its image, shedding its reputation as an opaque organization and building legitimacy for its mission to protect citizens from foreign threats.

Threats Can Stem From Foreign Contacts, Media, and Travel

Several MSS WeChat posts suggest that foreign espionage agencies recruit PRC citizens via social media. The first in a series of posts from October titled “National Defense Line: Analysis of Typical Cases of National Security Agencies” (全民防线——国家安全机关典型案例解析) detailed an example of this. It described a foreign spy enticing and bribing PRC citizens to gather intelligence on their behalf. Xiaojie (小杰), a university student in Tibet, allegedly received a social media message from an attractive blogger who wanted to film a travel video in the province. The blogger asked Xiaojie to help film a few locations in Tibet, for which he would be paid, and sent him a list. Luckily, Xiaojie was a model student, whose national security education helped him realize that some locations were adjacent to military installations. Upon discovering this, he called the MSS hotline to notify the authorities. The ministry soon found that the same “blogger” had made similar approaches to over 100 people (WeChat/MSS, October 12).

Another warning sign, according to the MSS, is exposure to foreign entertainment content. In an article from September, the MSS drew attention to platforms that provide users with access to illegally broadcast overseas propaganda content under the guise of “shareware” (共享软件) and “customized hardware” (定制硬件). The MSS said that once software of unknown origin is installed in smart TVs, receivers, or mobile phones, the illegal broadcast of overseas counter-propaganda not only violates network security regulations but also “spreads bad content, pollutes the social and cultural environment, and poses a double challenge to national cultural security and the privacy of citizens” (传播不良内容,污染社会文化环境,造成对国家文化安全和公民隐私权的双重挑战). The ministry called on citizens to jointly safeguard national security by not downloading illegal software, not installing illegal hardware, and “purifying” (净化) cyberspace (WeChat/MSS, September 19).

The MSS also casts suspicion on scholarly exchange. One post from August says that foreign intelligence agencies use academic exchanges to recruit individuals and infiltrate institutions, and provides several examples so that PRC scholars know what to look out for. In one example, a foreign spy approached a PRC researcher surnamed Zhang while on a tour at a foreign university, offering paid consulting work. Zhang accepted, and subsequently sold large amounts of classified data to the spy. Zhang was ultimately caught and arrested. In another example, Mr. Liu, a volunteer for a biological research magazine, accepted an invitation to observe and photograph the activities of a certain species inhabiting an urban area. After sending through some photographs, he received requests for more detailed information about the area. Suspicious, Liu called the MSS hotline. Unlike Zhang, Liu was rewarded for his work. The clear message from these contrasting examples is that citizens should report suspicious behavior. They are even incentivized to do so (WeChat/MSS, August 27).

Foreign spies even pose risks to PRC tourists overseas. According to a WeChat post from over the summer, citizens should “beware of spy traps” (防范间谍陷阱). They should make sure not to disclose information about their work unit or research field, and if approached by any foreign espionage or law enforcement agency for interviews, they should request consular protection and report the case to national security authorities upon their return home (WeChat/MSS, June 28).

Conclusion

The breadth of domains touched on in MSS messaging suggests that the ministry sees potential threats wherever PRC citizens night come into contact with foreigners—at home, in cyberspace, and overseas. Its rhetoric encourages paranoia about foreign spies. But it also feeds into broader CCP messaging that fosters anti-U.S. sentiment. Some posts slip into overt language on this. In August 2023, the MSS accused the United States of fabricating the PRC’s threat to U.S. national security and pursuing hegemonic security for global expansion (WeChat/MSS, August 13, 2023). This is entirely in line with constant messaging from other parts of discourse apparatus that discuss the “hegemonic playbook” of the United States (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 2023; China Brief, September 12, October 31). In this way, the aims of MSS messaging are twofold. One is to shore up national security and enhance public education on security threats. The other is to instill suspicion and hostility toward the United States and the West more generally.

Notes

[1] The paranoia is warranted. On May 1, the Central Intelligence Agency released two high-production quality recruitment advertisements across Western and Chinese cyberspace targeting PRC nationals (YouTube/CentralIntelligenceAgency, accessed November 5).