New Year with Old Burden: Political Limbo and Unclear Purpose to Haunt Moldova in 2013

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 3

By:

Three key political trends shaped Moldova’s political landscape during the last year. First of all, there has been an observable erosion of purpose and unity in domestic politics, affecting the coherence of Moldova’s diplomacy. Furthermore, one of the most severe gaffes of Moldovan political leaders was falling victim to their strategic misunderstanding of Russian foreign policy. Finally, Moldova underutilized the benefits offered by the political sympathy it enjoyed among political elites in the European Union and the United States.

One of the essential ingredients of a successful foreign policy is achieving unity of purpose and effort among domestic leading political actors. Last year, as previously, was marked by an increasing division in Moldova’s foreign policy strategic priorities between the incumbent Alliance for European Integration (AIE) and the opposition Communist Party (PCRM), which has tilted toward Russia (pcrm.md, December 10, 2012). These disagreements on whether Moldova should continue its European integration efforts, favor instead strengthening its ties with the Russian Federation and its regionally-controlled structures (see EDM, December 11, 2012), or pursue a combination of the two have been slowly wearing out the AIE itself.

Even though publicly all three leaders of the AIE confirmed their unconditional support for European integration through continuous institutional reforms and democratic consolidation, the reality is much more dim. Both formal and informal state institutions are captured by interest groups supporting the three political parties forming the AIE—the Liberal-Democratic Party (PLDM), Liberal Party (PL) and Democratic Party (PDM). Undoubtedly, there has been an obvious and considerable improvement in the performance of state institutions in comparison to the governments run by PCRM until 2009. However, this is hardly the result of the individual AIE members’ benign efforts at reforms. The competition between the three AIE parties for redistribution of state resources as well as control over lucrative businesses and formal institutions has ironically created the checks and balances that favored the observed improvement in governance during 2009–2011.

Last year, however, was one of stagnation in this regard. Key law enforcement agencies, such as the Ministry of Interior and the Security and Intelligence Service, but also the Office of the Public Prosecutor and the Ministry of Justice, are guarding select parties’ interests and staunchly resist reform. The government is obstructed by these interest groups inside the AIE and cannot optimally mobilize its resources to promote effective policies domestically or internationally. These fissures among the incumbent AIE members have been duly noted by Moscow, which is eager to explore them with the intention to strengthen its leverage over Chisinau’s internal and foreign affairs (see EDM, September 10, 2012).

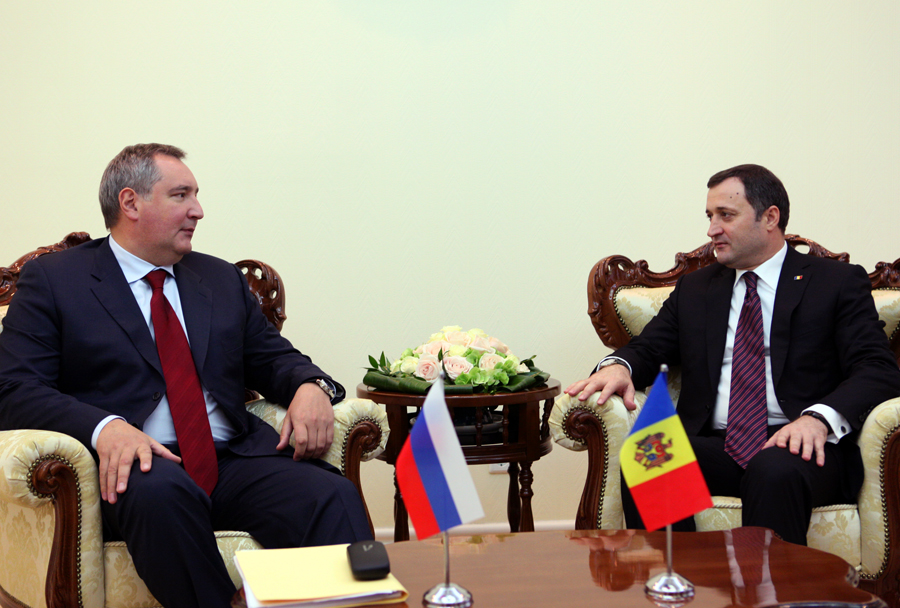

This domestic political background sheds light on Moldova’s policies toward Russian in general and the Transnistrian conflict in particular. Incapable of figuring out ways to resist continuous and increasing Russian pressure, the Moldovan government has slowly but steadily succumbed, giving up concessions to Moscow (kommersant.ru, November 20, 2012; ng.ru, December 29, 2012). In an extensive interview to a local TV station in Tiraspol, Dmitry Rogozin, the Russian presidential envoy for Transnistrian conflict-resolution, insisted that the Moldovan government has no other choice but to accept all of Russia’s demands. He pointed out, however, that the Kremlin is careful not to push things too quickly, as it does not want to rock the boat in Chisinau and awaken anti-Russian feelings among AIE voters (vesti.md, November 20, 2012). Russia’s strategy, according to Rogozin, is to create facts on the ground, while having the Moldovan leadership turn a blind eye to it, and then present the West with cases of fait accompli (see EDM, December 11, 2012).

Last year, Moldovan-Russian diplomatic relations were clearly summarized by the aforementioned Rogozin interview and revealed a number of highly worrisome facts. Apparently, Moldova’s government, in negotiations with Russian officials, attempted to hide behind the explanation that it could not openly accept the Kremlin’s demands due to domestic public opposition and fear of massive protests. This naïve trick is nothing but a major foreign policy miscalculation of the current Moldovan government and has set a ticking time bomb in its diplomatic relations with Russia. While it relieved Moldova of some of the Kremlin’s pressure in the short term, it has also suggested to Russia’s leadership that the Moldovan government can actually be pushed into submission and encouraged Moscow to further invest resources and efforts to continue this strategy over the long term. Russian experts have labeled this incrementally submissive diplomacy that Moldova carried out last year toward Russia as the “Moldovan model.” And it is now suggested that the Kremlin is developing a similar approach to its relations with Bidzina Ivanishvili’s new government in Georgia (ng.ru, November 11, 2012).

The previous year also emphasized the decreasing ability of the “5+2” negotiations to achieve diplomatic breakthroughs. This failure is explained by their format, in which Russia made sure to limit the capacity of the EU and the US to influence the agenda of its protégé, the Transnistrian leadership. Moscow has also encouraged personal diplomacy with Chisinau and the EU, making the process non-transparent, and allowing Russia to divide its opponents’ efforts. Specifically, the Kremlin took sufficient pain to distance Washington from the negotiations process outside the “5+2” format, playing on the EU’s foreign policy ambitions and discouraging the Moldovan government from cultivating US support.

There are no signs or hope that things are going to change in 2013. The current Moldovan leadership will continue to employ strategies entrenched in defeatist thinking and an inferiority complex toward Russia. AIE-affiliated interest groups will become more vulnerable economically to Russia as Moscow will encourage their further investment into the Russian state-controlled economy. These factors shall discourage Chisinau from building its own capabilities to generate economic and political costs to Russian involvement in Transnistria. Then, by making itself even more susceptible to Russian influence, Moldova will actually attract less essential political support from the EU and the US, as it will be perceived by the West as too costly. Finally over the course of 2013, Russia will likely continue to be successful in discouraging the Moldovan government from inviting substantial US support and actively involving US-based actors.