Pakistan Beats Kyrgyzstan to Gain UN Security Council Seat

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 207

By:

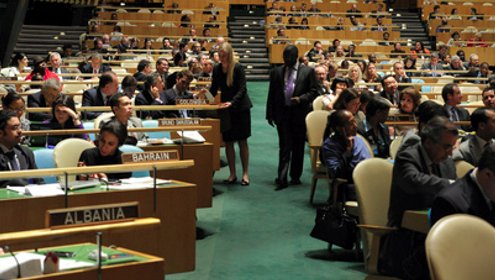

On October 18, Hina Rabanni Khar, Pakistan’s first female foreign minister, met with Roza Otunbayeva, Kyrgyzstan’s first female president, in Bishkek to persuade Kyrgyzstan – its competitor for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council – to drop out of the race. Kyrgyzstan declined, but Pakistan emerged victorious nonetheless, having secured the seat on the Asia bloc for the seventh time in its sixty four-year history of independence.

For many, the view of Munir Akram, Pakistan’s former representative to the UN, explains Islamabad’s success. “Pakistan is a very large country [and] it has vital national interest in the issues on the agenda of the Security Council,” he said before the Assembly vote that took place on October 21. “Kyrgyzstan, I think, has never as such made vital contributions to international peace and security. Pakistan is the largest troop contributor to [UN] peacekeeping operations. I think the comparisons in the contribution that are made and can be made by the two countries are very stark and very clear,” Akram argued (www.rferl.org, October 19). Pakistan, the world’s sixth most populous country with the world’s sixth largest nuclear arsenal, has over 9,000 troops in eight UN Peacekeeping Missions worldwide (www.ftpapp.app.com.pk, October 21).

Kyrgyzstan is a small country but it does its share, and there are some benefits that could have been derived for the international community had it gained a seat on the UN Security Council. Talaibek Kydyrov, the Kyrgyz Ambassador to the UN, says that Kyrgyzstan sends peacekeepers to Africa each year. Around 16 Kyrgyz peacekeepers serve around the world today, though their number was 45 a few years ago (www.rferl.org, October 19; www.gazeta.kz, October 21). But it was Roza Otunbayeva who defined the need for the international community to support the country’s aspirations: “The Kyrgyz Republic as a member of the group of landlocked countries, of the group of small countries with economies in transition, and as a young democracy with a multifaith population, supports the need for wider representation of all categories of countries in the Security Council” (www.rferl.org, October 19). Commenting on the unfolding race between Pakistan and Kyrgyzstan over the UN Security Council seat, the Kyrgyz Ambassador to Pakistan Alik Orozov said Kyrgyzstan chose the parliamentary system and that “this is our beginning towards democracy and we need support from the world” (www.dailytimes.com.pk, October 21).

That support turned out to be insufficient. Kyrgyzstan, the only candidate from Central Asia, received only 55 votes. Islamabad, however, was backed by 129 of the 193 member states in the General Assembly, allowing it to replace Lebanon from January 1, 2012. However, Pakistan’s weaknesses, not strengths, assured its victory. Some analysts claim that Islamabad plays a dual role of both the spoiler and stabilizer in Afghanistan, which is scheduled to see a drawdown of coalition forces by 2014. Many powers accuse Pakistan of aiding militants, engaging in international terrorism, and playing a destructive role in the broader region plagued by the Pakistani-Indian conflict over Kashmir. Concerns over Pakistan’s record and potential for nuclear proliferation amid an increased terrorist threat to its homeland only further underscores the need for the international community to work with the Pakistani authorities on solutions that would bring stability to the country, its troubled neighbor, and the broader region. Bringing Islamabad into the world’s security body, some analysts argue, would help major players discipline Pakistan and shape its policies, viewed as both a source of problems and solutions.

Kyrgyzstan’s governance record is not without its flaws. It has experienced two regime changes in the last six years and a violent conflict between two major ethnic groups that claimed hundreds of lives. It suffers from prevalent poverty and has a shaky political system as it seeks to build a more just and democratic polity. But it has made advances that some fear and many more hope will be replicated in the post-Soviet space. Two of its corrupt regimes were brought down well before the emergence of the Arab Spring, raising prospects for better socio-economic life and the evolution of a parliamentary system of governance that continues to face strong opposition at home and abroad. As a small developing nation, it has pursued a relatively more open and liberal political and economic agenda – no small feat in Central Asia, a region defined by authoritarian regimes. The country is therefore landlocked geographically and also in political terms. Its pro-democratic aspirations face strong opposition from the region and major powers on the region’s frontiers.

Nevertheless, Kyrgyzstan has hosted a key logistical base for coalition forces for many years, in part because relying on Pakistan for secure supply routes has proved problematic. As a post-Soviet and largely Muslim nation with a secular form of government and pro-democratic ambitions, it also offers an interesting model of development for the region and beyond.

The presidential elections held on October 30 in Kyrgyzstan may change the country’s course, just as ongoing domestic and regional economic and security challenges may fundamentally reshape Pakistan. Hope remains that Islamabad’s non-permanent seat at the UN Security Council – an achievement considering Pakistan’s internal and external record – will help its authorities lead based on the country’s strengths, not weaknesses, and in a sustainable way.