Perspectives for Israeli Gas in Southern Gas Corridor Hampered by Economic Limitations

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 186

By:

Israeli Ambassador to Azerbaijan, Dan Stav, announced, on November 6, that his country was “considering the possibility to transport its natural gas to Europe via the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline [TANAP] through Turkey.” Earlier, on October 14, Turkish presidential advisor Cemil Ertem declared that Turkey wants to connect Israel’s gas supplies to the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC)—an energy transit corridor from Azerbaijan to Europe, of which TANAP is a key link (Trend, November 6; Azernews.az, October 14). Several months before those statements, on June 26, Israel and Turkey agreed to normalize their relations with the hope that a diplomatic rapprochement might smooth the way for an agreement on transporting Israeli gas to Turkey. Such a deal would diminish Turkey’s gas dependence on Russia and help Turkey diversify its sources of energy supplies (Hurriyet Daily News, June 26).

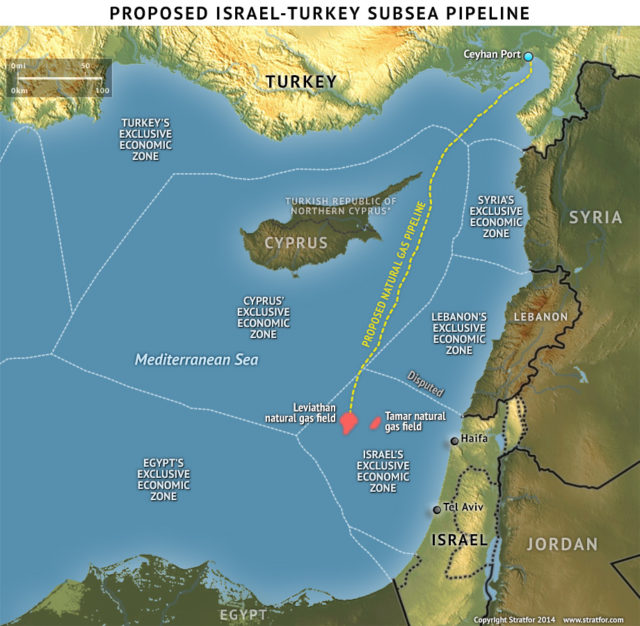

In 2009 and 2010, the United States–based company Noble Energy and Israel’s Delek Drilling discovered two giant offshore natural gas fields—Tamar and Leviathan, respectively—in Israeli waters in the Mediterranean Sea. Tamar field (283 billion cubic meters of reserves), was supposed to meet Israel’s domestic consumption, while production at the Leviathan field (510 bcm of reserves) will likely be export-oriented for European markets (Haaretz, August 12, 2009 and June 2, 2016; Washingtoninstitute.org, June 23, 2016). Furthermore, in 2016, a group led by Isramco Negev and Modiin Energy discovered around 252 bcm of natural gas at the Daniel East and Daniel West fields, close to Gaza’s waters (Haaretz, January 17).

Although the large Leviathan and Tamar gas fields were discovered in 2009 and 2010, long-running discussions on their development, coupled with regulatory disputes within the government, have delayed exploration works and corporate investment decisions. In 2014, Israel’s antitrust authority claimed that Noble Energy and Delek Drilling’s outsized roles in the Tamar and Leviathan fields were not compatible with competition rules in the domestic natural gas market and could push natural gas prices up. The right-wing Israeli government later agreed that the companies could retain their stakes in Tamar and Leviathan, but on the condition that they sell shares in several smaller fields (Natural Gas World, July 13, 2015; December 28, 2015).

The most straightforward option to transport Israeli gas from the Leviathan field to Turkey is by constructing an undersea pipeline, dubbed the “Leviathan-Ceyhan Pipeline,” through Cyprus’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). During the October 13 meeting of the World Energy Council, in Istanbul, Israel and Turkey agreed to examine the feasibility of such a pipeline. However, its construction through Cyprus’s waters is constrained by the level of Turkish-Cypriot diplomatic rapprochement. The problem of dealing with Cyprus’s EEZ is a prerequisite for moving forward. Moreover, the actual economic viability of the Leviathan-Ceyhan Pipeline project is itself questionable. However, successful energy cooperation could reconcile Turkey’s relations with Cyprus and simultaneously strengthen Turkey’s hand in its relations with the European Union. Yet, this project will challenge Russia’s Gazprom, which is eager to complete its Turkish Stream natural gas pipeline’s two legs as soon as possible before additional foreign gas can enter Turkey (Natural Gas World, September 23, 2013 and August 7, 2014; Daily Sabah, October 2, 2016; Iene.eu, January 6). According to Sohbet Karbuz, the director of the Hydrocarbons, France, Mediterranean Energy Observatory, “a potential gas pipeline from the Leviathan field to Turkey could connect to the BOTAŞ pipelines or to TANAP.” But the combination of transport costs and Israel’s current gas prices framework makes Israeli gas unattractive in the European market, Karbuz has argued (Trend, October 14).

Israel could feasibly also use the planned liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal at Vassilikos, Cyprus, or Egypt’s current unused LNG export terminals in Idku and Damietta to sell its gas to European markets (Daily News Egypt, July 14). However, none of the Leviathan field’s corporate partners expressed interest in sharing the financial burden of transporting gas via Vassilikos. Noble Energy, meanwhile, held talks with the United Kingdom’s BG Group to use Egyptian LNG terminals to re-export Israeli gas to Europe. In October 2013, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that 40 percent of Israel’s proven gas reserves can be exported. And more recently, an arbitration dispute between Egypt and Israel was finally settled. Therefore, the transportation of Israeli gas via Egyptian LNG facilities could gain momentum (Natural Gas World, May 1, 2014 and September 22, 2014; New Times, November 20, 2014). However, the combined costs of production, liquefaction, shipping, transporting, and re-gasifying would likely make Israeli gas to the EU much more expensive and non-competitive compared with Russian gas shipped via pipelines to Europe (Caspiandc.org, June 24).

Israeli gas could alternatively make its way to European markets by being pumped directly into the Southern Gas Corridor. One option is to deliver the gas through the planned Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline (EMP), which will link up with the Greek national gas transmission system, and then though to the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP—the final leg of the SGC, which will terminate in Italy). The 1,300-kilometer-long EMP is supposed run from Israel’s Leviathan field, via Cyprus, across the island of Crete and onto the Greek mainland. It is projected to cost $5 billion to construct, and has a planned capacity of 8 bcm per year. Although the EMP project was included in the EU’s Projects of Common Interest (PCI) list, the proposed pipeline currently lacks clear financial backing. Some issues (technical and financial) remain before the construction and implementation of the EMP can commence (New Times, November 20, 2014; Globes.co.il, October 27; Natural Gas World, December 15, 2014 and May 8, 2015). Notably, the construction of this offshore pipeline may turn out to be more expensive than predicted and technically complicated due to the depth of its undersea route. In addition, the EMP is not cost-efficient given the small volume of gas the pipeline will bring to Europe. Compared to Europe’s overall annual gas consumption and the amount supplied every year by Russia (158.6 bcm in 2015), Israel’s contribution would be a rather small drop in the bucket.

Given all the outstanding political, technical and financial issues, as well as prospective plans to bring more natural gas into the SGC from Iraq, Iran, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, Israel’s gas export plans via the SGC remain a distant hope for the time being. Therefore, it is safe to assume that, for now, Israel will continue to focus more on reaching agreements with Jordan and Egypt to supply its immediate neighbors due to their geographical proximity.