Perspectives on the Islamist and Salafist Parties in Egypt: Similarities and Dissimilarities

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 38

By:

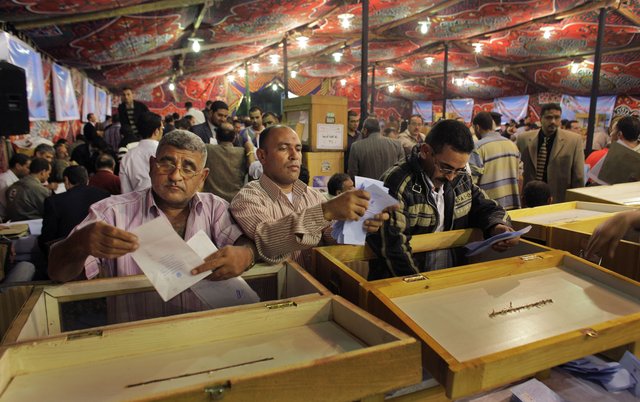

As part of the growing political process that opened up after the fall of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, there are now fourteen Islamist parties in Egypt, a dramatic change from less than a year ago, when all such parties were banned. These religious parties mushroomed after some were approved by the Committee of Political Parties and others after a decision was passed by the Administrative Court endorsing their establishment. [1]

Without a clear cut separation between the religious and the political, the Islamic movement in Egypt has recently tended towards political factionalism. Accusations and counter accusations have become common between various groups; the Fadhila Party, for instance, accused the Assla Party Chairman, Major General Adel Abdul Maqsood, of stealing 3500 records of party members when he left the party and adding them to the members’ list of his own party. This accusation was rejected by Abdul Maqsood, saying the remaining Fadhila members are the ones who abandoned the party when they tried to hijack the party by merging it with non – Salafist parties to form a single political front. [2]

Many other Islamist parties withdrew from the Democratic Alliance (al-Tahalof al-Dimqurati) led by the Muslim Brotherhood’s new political formation, al-Hurriyya wa al-‘Adala (the Freedom and Justice Party) when it became clear the Brothers wanted to monopolize the election lists for the Egyptian parliamentary elections scheduled for November 28, 2011 and the Shura Council election on January 22, 2012. The Nour Party withdrew from the group due to what is perceived as the alliance’s support of secularism.

The Salafist groups largely declared their opposition to the Egyptian Revolution, though some Brotherhood youths participated in the Revolution’s leadership. In spite of the fact Gama’a al-Islamiya (GI) distanced itself from the Revolution and did not attribute any of its struggles or achievements to itself, the Salafist groups have been among those most ready to exploit Egypt’s post-revolution politics and the least flexible in the face of what is sees as policies contradicting Salafist objectives, such as reevaluations of concepts such as citizenship and nationality. The Salafists have also accused the Revolutionary youth of being fanatics or even traitors.

The Salafist stand on the Coptic issue became evident in a series of violent incidents following the Revolution,

- On March 4, the Two Martyrs Church in the Giza Province village of Soul was torched by a Muslim mob. Local Copts remain angry after prosecutors declined to charge anyone in the attack (Ahram Online, April 13).

- Violent clashes between Copts and Muslims over another church burning on March 8-9 left at least ten dead and hundreds injured in the Moqattam district of eastern Cairo (Egypt.com News, March 9).

- In April, Salafists joined the Muslim Brothers in a two-day protest in Qena to oppose the appointment of a Coptic governor, General Emad Shehata Michael (Ahram Online, April 16; al-Masry al-Youm, April 18).

- In May, Salafists assaulted one church and torched another in a violent sectarian clash provoked by a local Muslim who claimed his Christian wife was being held inside the church after converting to Islam (al-Gomhurriya, May 9).

The Salafists’ insistence on a national Islamic identity after the revolution and their animosity towards religious minorities are a basic and prominent element in the discourse of the Salafist political parties. In the 10,000 word manifesto of the Salafist Nour Party, the terms “non-Muslim” and “citizenship” were each mentioned only once, as was the term “civil state.” “Human Rights” was only mentioned within the context of the right to healthcare. “Democracy” was mentioned twice, but only within the context of Islamic terms of reference. [3]

The Salafist al-Asala (Authenticity) Party seems closer in its discourse to Sayid Qutb’s political thought than it is to the Salafist line of thought. The party emphasizes that their first principle is governance based on “the divine law (Shari’a) for its people and the enforcement of this law, as well as annulling all the other laws that are in contradictions with that of Allah, and never to accept man-made laws and only embrace the divine laws of Allah” (al-Masry al-Youm, October 16).

The Islamist parties and al-Haya’a al-Shari’a lil Islah are currently seeking to unite the efforts of the Islamists to endorse an Egyptian Islamic constitution.

In spite of all the apparent similarities among all these parties and their agreement to stifle democracy, citizenship and governance, one can notice three basic contradictions common to their manifestoes and practices:

1) The parties have allowed political competition to challenge their common Islamic purpose in establishing an Islamic state in post-revolutionary Egypt. This competition is manifested in elections, political conflict, the formation of alliances against other parties and the accusations and counter-accusations that dominate relations between the Salafist parties.

2) Egypt’s Salafist parties have incorporated nationalism into their political platforms, a deviation from usual Salafist practices. Salafist parties have regional and nationalistic ambitions such as forming an Islamic axis with Iran and Turkey to further the establishment of a revived Caliphate, as mentioned in the manifestos of the Bena’a wa’l-Tanmiyya (Building and Development) Party, the party of the al-Gama’a al-Islamiya. [4] Other Salafist parties have issued calls for an Arab unity axis or have issued similar nationalist calls.

3) Once the struggle for constitutional reforms began, the Islamist parties unanimously agreed on opposing and challenging the sectarian parties and civil organizations. To this end they decided to carry out a media and religious battle against them before the elections slated for November. On the other hand the Salafist parties completely identify themselves with the Army and its policies designed to open the political process (Ikhwan Online, October 12). The spiritual mentor of the Salafist school, Yasser Borhami, described the sectarian parties as “cartoon infidels that are not worthy of any alliance” (Elbadl.net, October 8).

The post-Revolution proliferation of Salafist political parties is actually impeding their progress towards establishing an Islamic state in Egypt. Political discord prevents the creation of an effective alliance and the parties’ close identification with sectarian street violence is unlikely to enhance their appeal to more moderate Egyptian Muslims.

Notes:

1. Among the Salafist parties to be recognized by the Party Committee in Egypt are al-Amal al-Islami (Islamic Action), al-Hurriyya wa al-‘Adala (Freedom and Justice Party) the Wasat (Center) Party, al-Nour Party, Asala al-Salafi and the Bena’a and Tanmiya Party. The latter was approved by the Administrative Court after it was rejected by the Party Committee because its platform is based on religious beliefs. It was not clarified how this party differs from the other previously approved. The Salafi al-Fadhila Party is still waiting to be approved by the Committee, as is the Tawhid al-Arabi (Arab Union), an offshoot of al-Amal al-Islami. Other parties are still preparing their papers to be presented to the Committee include al-Salam and Tanmiya Party (led by some former jihadists), the Egyptian Tayyar Party, al-Wasatiya Party (led by Karam Zuhdi, the former Chairman of the Shura Council of the Jama’a Islamiya Party), the Masr al-Bena’a Party( led by Nidal Hamad) and the Nahda Islamic Party (led by Muhammad Habib, former Deputy Supreme Guide of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and Dr. Ibrahim al-Za’afarani, a former member of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Shura Council.

2. https://www.muslm.net/vb/showthread.php?t=443388

3. Hani Nasira: “Islamists Contrasts, A Case of al- Nour Party,” al-Hayat, July 3, 2011.

4. For the Bena’a wa’l-Tanmiyya Party manifesto, see https://misralbenaa.com/.