Poland on the Frontlines Against Russia’s Shadow War

Poland on the Frontlines Against Russia’s Shadow War

Executive Summary:

- Russia’s shadow war against Poland combines low-level sabotage, insider espionage, informational warfare, and cyber‑attacks.

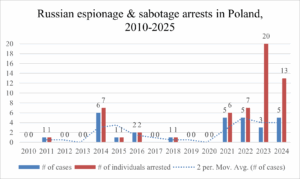

- Between 2010 and 2025, Polish authorities closed 30 subterfuge cases, leading to the arrests of 61 individuals—19 cases and 49 arrests since 2021—accounting for roughly 35 percent of Europe’s Russian-linked espionage and sabotage arrests.

- Recruits for these operations have shifted from ethnic Poles to predominantly Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian nationals. Their missions aim to reduce support for Ukraine, disrupt decision-making, erode social trust, and stoke extreme and disruptive politics.

- Countering the threat will require holistic countermeasures spanning media literacy, institutional hardening, and increased NATO intelligence cooperation.

Poland’s Digital Affairs Minister, Krzysztof Gawkowski, warned on May 6 that Russia is mounting an “unprecedented” cyber‑interference campaign aimed at skewing the vote away from frontrunner Rafał Trzaskowski ahead of the presidential elections scheduled for May 18 (TVP World, May 6). According to government reports, “eastern actors” have more than doubled their attacks on critical networks—probing water and sewage systems, power grids, and even the National Health Fund—and are simultaneously unleashing waves of intentionally false information designed to stoke political extremism on the eve of the elections (TVN24, April 15).

Russia has evidently intensified its subversive “shadow war” against leading NATO states in tandem with its war effort against Ukraine since February 2022. As a frontline NATO member, the principal military force in Central-Eastern Europe, and the main transit hub for Western aid to Ukraine, Poland has become the primary target for Russian subterfuge. Subterfuge in this case includes espionage, hostile reconnaissance, sabotage operations, cyber-terrorism, targeting society with false reports, and political influence campaigns. Poland tops the list among European states, accounting for roughly 35 percent of all known cases culminating in arrests. [1] Although subterfuge as a component of war is an established Russian tradition, the term “hybrid” is now widely used to highlight innovations in the way Russia coordinates these subversive tools into unified actions just below the threshold of open war (see Jamestown Perspectives, May 2).

Since 2021, the Polish counterintelligence agency ABW (Agencja Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego) has posted 19 cases of Russian subterfuge, leading to the arrests of 49 individuals on charges of espionage or sabotage. Extending the timeframe to 2010, the figure rises to 30 cases, involving 61 individuals. [1] The actual footprint of these activities is undoubtedly wider. As a statistical guideline, the number of arrests reflects only the number of foiled operations, a figure then decided by the number of cases that the ABW deemed acceptable to inform the public. Publicizing a case may either accelerate or compromise the dismantling of adjacent networks, while different countries treat espionage according to different legal parameters. The Polish ABW and the Estonian equivalent, KAPO (Kaitsepolitseiamet), are notoriously aggressive, whereas Western agencies tend to be more tight-lipped (Warsaw Institute, March 12, 2018).

On February 23, an investigation by the Polish TV station TVN depicted some of the typical ingredients of Russian covert actions, including Telegram, cryptocurrency, disaffected youths, and a propensity for destruction and arson (TVN, February 23). Portraying the case of a 16-person spy ring dismantled over the course of 2023, the TVN investigation traced their experiences from recruitment, one having been a promising Russian hockey star for the Polska Hokej Liga (Polish Hockey League) club Zagłębie Sosnowiec, to their espionage and sabotage activities and arrests. This particular case was not an isolated occurrence. In 2024, Polish authorities posted the arrest of a structurally identical 12-member ring linked to fires at an IKEA warehouse in Vilnius, Lithuania and a paint factory in Wrocław, Poland (Wyborcza, May 20, 2024). Beyond operational support for Russia’s war effort, these operations intend to terrorize and undermine social trust. By co-opting local civilians and newly-welcomed refugees to betray their own country, Russian subterfuge stokes social divisions and compounds cynicism, then paving the way for extremist and disruptive politics (Riehle, “Ignorance, indifference, or incompetence: why are Russian covert actions so easily unmasked?” January 30, 2024).

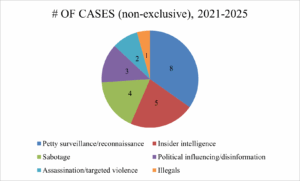

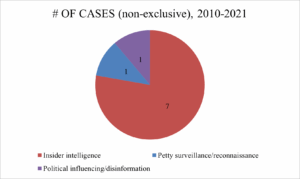

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, petty reconnaissance and sabotage missions have formed the lion’s share of Russian activity in Poland. This represents a marked shift from the 2010s, a time characterized by conventional espionage activity (see Figure C below). “Petty” denotes the crude operational level of these missions with a low degree of planning and risk. The recruitment blueprint is rough-hewn, yet effective. One of the most common methods involves using Telegram bots to recruit susceptible individuals—often vagrant types, marginalized youths, refugees, or budding Russophiles—to carry out tasks such as photographing military bases, railways, or individuals of interest on a pay-to-hire basis (OCCRP, September 26, 2024; see EDM, April 9). As for sabotage and acts of targeted violence, Russia’s practice of exploiting pre-existing criminal gangs has been well documented (Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, November 2024). Russian reconnaissance and sabotage operations in Poland have mainly targeted military bases, airfields, and adjacent transportation networks straddling the country’s eastern flank. The aforementioned 16-member network dismantled in 2023 was in charge of installing camera surveillance systems around the Rzeszów-Jasionka airport and planned to derail a train carrying military aid into Ukraine (Notes From Poland, December 19, 2023). Around the same time, Nikolai M. and Bernard S., a Belarusian citizen and his Polish accomplice whose surnames remain unpublished by the ABW, were arrested for reconnoitering rail and air facilities in the Lublin Voivodship, principally the military airfield at Biała Podlaska, between 2018 and 2023 (Belsat, May 11, 2024). In April 2024, the ABW arrested Pawel K. for relaying security information related to Rzeszów-Jasionka airport, intelligence that was suspected to furnish a plot to assassinate Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy while in transit (Notes From Poland, April 18, 2024).

Poland’s policy of harboring Russian and Belarusian dissidents has also imported violence. In July 2024, prosecutors in Łódź disclosed two foiled assassination and blackmail plots against Pavel Latushka—deputy head of Belarus’s United Transitional Cabinet—highlighting attempts to silence high-profile exiles through bribery, threats, and orchestrated violence (X/@PavelLatushka, July 22, 2024; RMF24, July 24, 2024). In April of this year, Polish authorities formally opened an investigation into the disappearance of Anzhelika Melnikava in late March, an exiled Belarusian opposition leader living in Poland. Her phone has since been traced to Belarus by Latushka (Polskie Radio, April 17). The Belarusian State Security Committee (KGB) also exploits Poland’s willingness to host refugees and dissidents to implant its operatives. Daria Ostapenko, a Belarusian OnlyFans model, arrived in Poland in January 2024 as a political refugee. She had been working with the Belarusian KGB, however, to gather intelligence on oppositionists living in Poland, which she mistakenly revealed to her friends during a night of drinking (Kresy, September 14, 2024). In March 2024, Leonid Volkov, a former colleague of late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, was attacked by hammer-wielding Poles in Vilnius on the orders of a Belarusian handler. While the case is often pegged to Russian intelligence services, an investigation by the Navalny team instead accused rival oppositionist Leonid Nevzlin of the Mikhail Khodorkovsky faction of the attack (LRT, September 13, 2024; see EDM, February 18). Nevertheless, the Volkov episode remains a worrying instance of Russian political violence spilling into Poland.

Insider Intelligence

The recruitment of insider assets remains a critical dimension of Moscow’s subterfuge. It presents the dual-edged threat of the theft of strategic intelligence and the corrosion of institutional trust from within. Since 2010, Polish counter‑intelligence has uncovered a dozen cases where Russian services recruited well-placed insiders to siphon high-value information from sensitive institutions. [1] In March 2022, the ABW arrested a Warsaw Registry Office employee who had unfettered access to city archives and was passing personal data on refugees and foreign residents directly to Russia’s foreign intelligence services, the SVR (Служба внешней разведки, Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki). The case exposed the vulnerability of bureaucratic information systems to espionage (Kresy, March 23, 2022). In May 2022, prosecutors charged Grzegorz M., a veteran of the communist‑era riot police (ZOMO), and his accomplice Radosław K., with conspiring to provide classified border‑control and migration plans to the Belarusian and Russian intelligence agencies. This demonstrated how recruitment can exploit institutional knowledge and private‑sector intermediaries (Government of Poland, May 5, 2022).

The ABW has cracked only one case from the “illegal” spy mold—deep undercover Russian agents operating under fake identities. Pablo González Yagüe, a reputed freelance war journalist from the Basque Country in Spain, was arrested for espionage while attempting to cross into Ukraine from the Polish border city of Przemyśl (VSquare, August 12, 2024). The case generated significant coverage given his decades-long track record as a war journalist. After a protracted investigation by the ABW, debates over González’ actual identity—sleeper agent Pavel Rubtsov—were ended when, in August 2024, he emerged from the same plane carrying fellow “illegals” Mikhail Mikushin, the Dultsevs, and others, back to Moscow (The Insider, The Moscow Times, August 1, 2024). Having formed relationships with Russian oppositionists and Ukrainian fighters, Rubtsov embraced Russian President Vladimir Putin on arrival.

Propagandists and Cyber-Warfare

Russian subterfuge in Poland has featured a relentless barrage of political‑influence, information warfare, and cyber‑attacks, each reinforcing the other to weaken public trust and political cohesion. This digital maskirovka (маскировка)—Russia’s doctrinal gamut of psychological operations designed to confuse and sow chaos behind enemy lines—is implemented domestically to maintain conformity and exported abroad to do just the opposite. In the twenty-first century, Russia has been the manipulator par excellence of online networks to achieve its geopolitical aims.

These efforts already gained attention in the 2010s. Stanisław Szypowski, a lawyer, was convicted in 2017 for transacting a classified LNG‑terminal report, recruiting informants for Russian military intelligence, the GRU (Главное разведывательное управление, Glavnoye Razvedyvatelnoye Upravleniye), and disseminating pro-Kremlin narratives in the Polish media. Since his release in 2021, Szypowski has seamlessly transitioned to high-level influence-peddling for Russia, publicly planting pro-Kremlin narratives at Ukraine‑reconstruction and fintech conferences attended by Polish ministers and diplomats (Frontstory, January 16). Mateusz Piskorski, founder of the small pro-Russian Zmiana party, used his Sejm platform to host Kremlin-backed militants and push anti-NATO, pan‑Slavic messaging—exchanging emails with Russian politicians—before his 2016 arrest for espionage on behalf of Russia and the People’s Republic of China (Frontstory, March 14, 2023).

Russia’s agents of influence are only a few faces of a sprawling informational warfare industry. Poland has faced a concerted campaign in which Russian dark‑net recruiters, false information outlets, and cyber‑sabotage units operate in concert to infect Polish political discourse and undermine critical infrastructure. If the Polish Ministry of Digital Affairs is to be believed, the country absorbs “60,000 to 70,000 attacks a month” from its eastern flank (TVN24, April 15).

Ahead of Poland’s 2023 parliamentary elections, coordinated troll-farms on Telegram and Facebook flooded Polish-language groups with false claims that NATO was planning to station nuclear weapons on Polish soil to stoke anti-Western sentiments (Demagog, February 19, 2024). At the same time, the Kremlin-aligned outlet Sputnik Polska published fabricated “leaks” alleging corruption within the main opposition party, then amplified them via Polish-language bots on X to undercut confidence in democratic institutions (Security & Defence, February 2024). In January of this year, Polish counter‑intelligence announced it had uncovered a Russian-inspired network on the dark web aimed at recruiting Poles to spread election-related disinformation and sow discord ahead of the presidential vote (eGospodarka, January 22). In September 2024, the ABW foiled a sabotage cell that had used stolen credentials to launch DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks against logistics firms handling military aid to Ukraine—part of a broader Russian effort to disrupt Poland’s support for Kyiv (TVN24, September 9, 2024). Additionally, in mid-2024, a coordinated cyber‑attack on the Polish Press Agency PAP (Polska Agencja Prasowa) spread false reports of a nationwide military draft before authorities restored the feed and debunked the hoax (Euractiv, June 1, 2024). Behind the scenes, CERT Polska detected renewed APT28 (Fancy Bear) probing of government networks, including the National Health Fund and air‑defense command systems, echoing tactics first seen in the “NotPetya” cyberterrorist attacks in 2017 (CERT Polska, May 8, 2024; The Record, May 9, 2024).

Strategic and Social Implications

The frequency and diversity of operations in Poland demonstrate the strategic priority Moscow has given to fracturing Polish society. By co-opting local civilians, including marginalized youths, corrupt professionals, and political proxies such as Piskorski, Russia manipulates social grievances to try and erode national morale. The insider‑asset cases also highlight vulnerabilities in bureaucratic and critical‑infrastructure systems that cannot be addressed by technical cyber‑defenses alone. Informational warfare and troll‑farm networks demonstrate how cyber-enabled propaganda can be synchronized with other tools in attempts to fracture Poland’s political consensus and weaken NATO’s eastern flank.

Early insider‑asset cases in Poland hinged on ethnic Poles betraying their homeland for money or adventure. Today, an overwhelming majority of those arrested for espionage and sabotage are Russian, Belarusian, or Ukrainian citizens, suggesting Moscow’s waning ability to turn Poles against their country (Notes From Poland, April 9). This is an encouraging development. Rather than fracturing Polish society, Russian subversion may be galvanized it. After the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, 97 percent of Poles expressed an unfavorable opinion of Russia, the most hostile response of all countries surveyed (Pew Research Center, June 22, 2022). The views of Ukraine are more nuanced. Data from Polish polling organization Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej (CBOS) indicates growing “Ukraine fatigue,” with a majority of Poles now agreeing that Ukraine should strive for peace even at the cost of its territory, while only 53 percent support accepting Ukrainian refugees—the lowest levels since Russia’s full-scale invasion began (CBOS, October 2024). Poland’s unity against Russian influence remains strong, but Moscow hopes that support for Ukraine may waver as the war grinds on. To uphold its defenses Warsaw must remain vigilant, reinforce media literacy, harden institutions, and enhance both military and cyber-defenses against evolving hybrid threats. In January, Deputy Prime Minister Krzysztof Gawkowski unveiled “Election Umbrella” (Parasol Wyborczy), a comprehensive cybersecurity and resilience program featuring intensified monitoring, multi‑agency coordination, and a nationwide media‑literacy campaign ahead of the May 18 vote (Government of Poland; PAP, January 28). How effectively Warsaw handles the plethora of hybrid threats will serve as a lesson for other democracies along NATO’s eastern front in confronting Russia’s incessant attempts to shatter their solidarity.

Note:

[1] Data drawn from Polish media, Agencja Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego (ABW), and Polish police records.