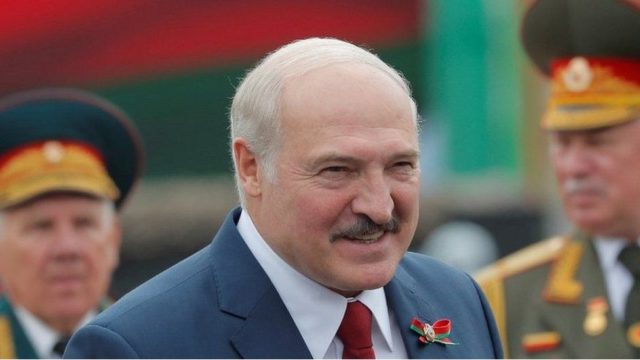

Popular Support for Belarusian Government Grows Amidst Fears of War Next Door

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 19 Issue: 100

By:

In late June, Belarusian Foreign Minister Vladimir Makei gave an extensive interview to Sputnik, a state-backed Russian media and propaganda outlet with affiliates in several countries, including Belarus. One of the overarching and persistent themes emerging from his remarks was the adamant rejection of the notion that Belarus is losing its sovereignty to Russia. And in this, the top Belarusian diplomat echoed a message that President Alyaksandr Lukashenka has also sought to present in recent months. Speaking to Sputnik, Makei insisted that there is a clear consensus to never even broach this subject in conversations with Russian dignitaries. Belarus and Russia are close allies that would never betray each other, he asserted, but each country retains its own policy (Sputnik.by, June 27). Admittedly, bilateral military cooperation is only tightening. Indeed, Russia is once again using Belarusian territory to launch air attacks against Ukraine, much like it did at the start of the 2022 re-invasion. Still, at least one area in Belarusian behavior notably diverges from Russia’s: allowing and then extending visa-free travel for Latvian and Lithuanian citizens until the end of 2022.

Along these lines, Makei launched a blunt rhetorical offensive. “In principle, it is normal,” he observed, “when people communicate with each other—and mind you, this is exactly what Western countries wanted during the Soviet era. And what do we see now? […] Now, maximum obstacles are being created to prevent Lithuanians and Latvians from entering Belarus. Up to denying them car insurance for the trip. Memos are issued to the effect that each visitor will be followed by a [Belarusian] security service agent. You can be arrested any time. You should not buy anything there, because food may be poisoned” (Sputnik.by, June 27). Shortly after Makei’s interview, visa-free travel was introduced for citizens of Poland, too, including visiting areas close to the border without a permit (Belta, June 30). This ruling coincided with Poland finishing the construction of a 5.5-meter-high wall along a 186-kilometer stretch of its border with Belarus. Polish Interior Minister Mariusz Kamiński explained that the wall separates Poland from the “ominous dictatorship of Lukashenka” (Deutsche Welle—Russian service, June 30).

Makei’s former subordinate, Pavel Matsukevich, who served as Belarus’s chargé d’affaires in Switzerland before resigning in September 2020 and is now an exiled opposition-minded analyst, uncovered some important asymmetries in Belarusian-Russian relations. He pointed out that whereas Lukashenka often holds face-to-face contacts with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, as he did again on June 30 (Sputnik.by, June 30), the opposite is not true. That is, Lavrov’s counterpart, Makei, has never been received by President Vladimir Putin in Moscow. That avoidance, hypothesized Matsukevich, stems from a fear that Makei (or somebody else) could enter Putin’s Kremlin office in one official capacity but symbolically exit it as Lukashenka’s anticipated successor. Likewise, Lukashenka often receives visiting heads of Russian regional administrations, but Putin never reciprocates in the same fashion (New Belarus, July 1).

Much like Makei, in the televised part of Lukashenka’s latest discussion with Lavrov, the Belarusian leader once more dismissed the idea of Russia moving to incorporate Belarus. You “are not so foolish as to incorporate somebody” (YouTube, June 30), remarked Lukashenka, reinforcing the impression of a true idée fixe. Psychologists have long observed that “disowned feelings are prickly emotions that you attempt to block out of awareness,” in part through repeated verbal denials (Psychology Today, November 23, 2020).

In his interview, Makei ridiculed the oft-repeated conviction of some Western politicians that “we hear the voice of the Belarusian people,” “so we will bring democracy to Belarus sooner or later.” They mistake some 1,000 plus renegades for the voice of the Belarusian people, asserted Makei. What is peculiar is that at least six of those alleged renegades—Pavel Slyunkin, Artyom Shraibman, Philip Bikanov, Gennady Korshunov, Katerina Bornukova and Lev Lvovsky—admit that popular trust in the Lukashenka regime is evidently growing. In a recently released report, they compare the results of two online surveys, the first conducted in October 2021 (1,500 respondents) and the second from May 2022 (1,024 respondents). And they conclude that in the latter case, those prone to trust the Belarusian authorities, combined with the regime’s diehard supporters, summarily accounted for 48 percent of all respondents; whereas, the same group made up only 38 percent half a year earlier. In other words, support for Lukashenka’s government has significantly increased in the meantime. Among the ardent opponents of the regime, there are more men, and they are more educated; representatives of this segment more often live in Minsk and have a higher income. In addition, the two surveys record a vast increase in polarization—that is, so-called social distance and mutual antagonism between the opposing groups of Belarusians. The authors of the report explain this growth in Lukashenka’s support by the ongoing war next door. And keeping Belarus effectively out of this war is popularly interpreted as a great achievement by the authorities. Quite a few people who evinced political neutrality at the time of the October 2021 survey, thus, become regime loyalists by May 2022 (Euroradio, June 28; Fes.de, June 26).

As has been noted multiple times (see EDM, March 22, June 13), by their sheer format, online surveys end up with samples skewed in favor of the opposition-minded public. That is because this segment of the population is more internet-active and because supporters of the regime are much more likely to refuse to participate in an undertaking (such as an online poll) that in any way looks to be linked to the opposition or its values. That implies that actual support for the Belarusian authorities may be even broader than reported.

Does that mean the regime has become a benign force? Surely not. However, neither the regime, nor the opposition can be thought of as the sole spokesman for Belarusians at large. On the one hand, this raises serious questions about the idea of forming a government in exile—in addition to the current public activism of opposition leaders residing outside the country. Zerkalo, a media outlet founded by a group of former Tut.by associates, left no doubts as to its skepticism regarding Pavel Latushko’s recent attempt to set up such a competing government (Zerkalo, June 27). On the other hand, the United States’ decision to locate its team of diplomatic envoys not in Minsk but in Vilnius, where it has interacted primarily with the office of Svetlana Tikhanovskaya (Belsat, April 21, 2021; By.usembassy.gov, February 28, June 9), increasingly looks like a misguided idea.