Pushing the “New Type of International Relations” in Latin America

Publication: China Brief Volume: 13 Issue: 15

By:

On July 24, Beijing hosted Jose Ramon Balaguer, head of the International Department of the Communist Party of Cuba—the latest in a series of bilateral meetings with Latin American countries running back to the spring (Xinhua, July 24). The rhetoric of these visits illustrates the effectiveness of Chinese diplomacy under President Xi Jinping in enlisting states of all kinds—from Cuba and Venezuela to Costa Rica and smaller Caribbean countries—to its vision of how states should behave. China’s willingness to approach these states in a balanced way is intended to demonstrate how different China’s approach to international diplomacy is from the United States. That is, Beijing appears to be approaching Latin American states as equals to avoid being associated with the imperialist legacies of the 19th and 20th centuries. Although the degree of commitment to Chinese ideas probably varies from state to state, this is a geographic area where China has few interests that conflict with the home government and its ideas may have the most potential.

Although the “New Type of Great Power Relations” is the more commonly known term, Xi gave a speech in Moscow where he expanded the terminology to a “New Kind of International Relations” (People’s Daily, March 24; Wei Wei Po [Shanghai], March 23). The core of the expanded concept was common development, meaning countries must respect each state’s right to pursue its own political and economic development. Xi also said the world’s increasing interdependence and non-traditional security threats meant that states should not pursue security unilaterally, but should rely on cooperative mechanisms to address their security concerns (“Out with the New, In with the Old: Interpreting China’s ‘New Type of International Relations’,” China Brief, April 25; People’s Daily, March 24). This more expansive “New Type” concept allows Beijing to bridge the gap between small or developing countries and great powers, providing a common framework for understanding “core interests” and peaceful development (People’s Daily Online, July 26; Guangming Daily, July 25).

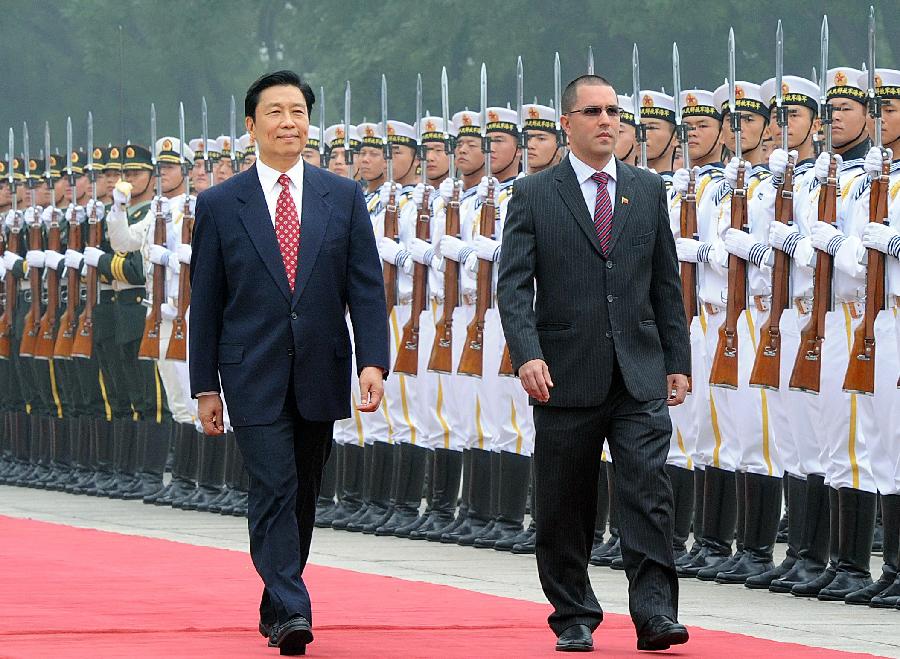

Beijing’s most successful efforts still probably are with the more anti-U.S. countries like Cuba and Venezuela, judging from how officials from Havana and Caracas speak publicly to their Chinese counterparts. For example, Cuban Interior Vice Minister Fernandez Gondin told Chinese Central Political-Legal Commission chief Meng Jianzhu “Cuba will continue to firmly stand by China on issues concerning its core interests” (Xinhua, April 9). When Politburo member Guo Jinlong visited Cuba in June, Cuban Vice President Mercedes Lopez Acea noted “Each country faced the task of building socialism with its own national characteristics.” Acea added that Sino-Cuban ties “had become a model of bilateral ties” between large and small countries based on “mutual understanding and mutual respect” (Xinhua, June 1). Even though Venezuela does not share China’s political system or communist legacy, Caracas still endorses Beijing’s political choices in precisely the way “New Type of International Relations” suggests. Venezuelan Vice President Jorge Arreaza said “China’s adherence to the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics is encouraging for other countries” (Xinhua, July 19). Arreaza also said the “Venezuelan people admire China for its commitment to the principle of mutual respect in international relations and its great contributions to world peace and development” (Xinhua, July 19). In a joint appearance with Chinese Vice President Li Yuanchao, the Venezuelan vice president added that Caracas “is ready to learn from China’s experience in development” (Xinhua, July 18). These remarks demonstrate the intent of all the governments concerned to deflect the pressures for democratic reform intrinsic to the U.S.-led international liberal order.

Even where such language does not fit, Chinese officials—in the case of Costa Rica meetings, National People’s Congress Chairman Zhang Dejiang—shoehorn the ideas into the conversation. Zhang told his interlocutors “China will firmly support Costa Rica’s adherence to the country’s development path in accordance with its own national conditions” (Xinhua, July 9). When President Xi visited Costa Rica en route to the Sunnylands summit with the United States in June, he told his counterpart Laura Chinchilla “The China-Costa Rica relationship is in a position to become a paradigm of cooperation between countries of different size and national condition.” The two countries “should push forward democracy in international relations and jointly safeguard the interests of developing countries as a whole” (Xinhua, June 4). Xi’s statements speak directly to Beijing’s assessment that the international system is becoming more multilateral—therefore, requiring a more democratized international system—and that each country should decides it’s own development path (Guangming Daily, July 25; Wen Wei Po [Shanghai], March 23). More importantly, China’s rhetorical treatment of Costa Rica demonstrates that Beijing’s position and its appeal are not confined to problematic governments.

The terminology associated with China’s diplomacy also shows that President Xi’s “New Type of International Relations” lacks novelty—indeed, some Chinese analysts concede this (People’s Daily Online, July 26). During Xi’s swing through Trinidad and Tobago where Caribbean leaders gathered to meet the Chinese president, Antigua and Barbuda Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer “thanked China for its aid to his country and lauded the Asian nation for its efforts to develop relations with Antigua and Barbuda on the basis of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” (Xinhua, June 3; China Daily, June 3). The five principles have been part-and-parcel of Chinese foreign policy since the 1950s. The equality of each country’s choice of political system and development path has long been a hallmark of how Beijing defends its own development path, socialism with Chinese characteristics. The “New Type” concepts, especially the broader one, probably are best characterized as a rhetorical evolution of China’s peaceful coexistence strategy (“China’s Coexistence Strategy and the Consequences for World Order,” China Brief, May 23).

Beijing’s continuing push for a “New Type of International Relations” deserves scrutiny, because of the concept’s potential ramifications for the international system. Although regional alternatives have diluted the influence of Western-led international institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, many Western aid and development organizations push governance and democracy promotion programs. For all practical purposes, China is undermining the legitimacy of such work. Additionally, China is doubling down and attempting to spread the principles that it used to justify its multiple vetoes of a UN-sanctioned intervention in Syria. Keeping focused on the Americas, how Brazil responds to China’s alternative to post-World War II notions of conditional sovereignty will be one of the more important indicators of how well Beijing’s diplomatic push is faring.