PUTIN-GYURCSANY MEETING STEERS HUNGARY’S GOVERNMENT ON THE “THIRD PATH”

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 3 Issue: 174

By:

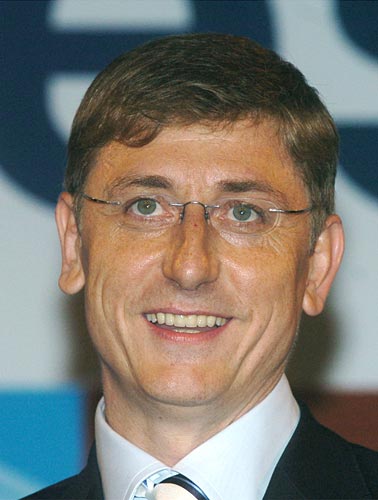

Hungary’s crisis-plagued government under Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany seems to have embarked on a “third-path” course between the institutional West, where Hungary belongs, and Russia toward which Gyurcsany and his closest associates seem increasingly to gravitate. The concept of a “Third Path” (Harmadik Ut) between the West and Russia has antecedents in Hungary’s right-populist and left-populist thought before and after World War II; but it has lost its rationale and forfeited any legitimacy since Hungary became a member of the European Union and NATO.

Hungary’s choice between the EU’s and Gazprom’s rival grand projects — the Nabucco pipeline for Caspian gas or the South European Gas Pipeline for Russian gas — has become a touchstone of the Gyurcsany government’s allegiances. Although the EU has declared its project to be a high priority for European energy security, Hungary’s government is holding talks with both sides while quietly signaling to Russia and Gazprom an actual preference for the latter option.

On September 18, Gyurcsany discussed this and other issues with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi. On the same day in Budapest, a political crisis broke out when public television aired the recording of a secret Gyurcsany speech to his Socialist party cadres, in which the prime minister openly and repeatedly admitted to have “lied” to the country. The government, he said, had concealed the gravity of the economic situation and doctored statistics in order to win reelection.

In the concluding news conference with Putin in Sochi, Gyurcsany acted as a sounding board on energy security. Implicitly and at times explicitly, he distanced Hungary from the EU’s evolving position on this and other issues. Endorsing the idea of mutual dependence between the Russian state monopoly Gazprom and European consumers, Gyurcsany obliquely cautioned Europe, “Those who do not understand something here will sooner or later go bust. We, Hungarians, do want to understand Russia” (NTV Mir, September 18). &ldqu o;Europe needs not just a common energy policy, Europe needs an open and goodwill-based cooperation with Russia, and we are linked to one another for long times to come. Russia offers a wonderful example of how to build these relations.” Hungary’s bilateral deals with Russia on gas transport and other energy projects, Gyurcsany went on, “Do not contradict, but rather favor Europe’s interests by making energy supplies more reliable and predictable” (a remark contradicting the EU position on the high-priority Nabucco).

Alluding to critics back home, Gyurcsany assured Putin, “We are determined to build relations with Russia for the long term … for which we sometimes must wage a fight in our own country” (Interfax, September 18). He also took pride in his ability to “find instant understandin g with the president of Russia.” Reporting the Sochi news conference, the independent daily Kommersant described Gyurcsany’s ingratiating behavior toward Putin and merriment over this in the audience (Kommersant, September 19).

No new understandings seem to have been reached in Sochi about building Gazprom’s South European Gas Pipeline (SEGP) from Turkey to Hungary. Bilateral Russian-Hungarian discussions on this project began in February, intensified in June and July (see EDM, June 30, July 3) and are ongoing, indicating the Hungarian government’s tilt in that direction, despite its having joined the EU-backed Nabucco consortium for Caspian gas. Gazprom and Hungary’s dominant energy company Mol (a Nabucco member) have created a joint company to study the feasibility of building transit and storage capacities in Hungary, targeting countries farther to the West.

Gazprom proposes to extend its Blue Stream pipeline — which carries Russian gas via the Black Sea to Turkey — by building the SEGP through the same countries that have joined the Nabucco project: Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, with a further extension to Italy. A choice of SEGP over Nabucco would institute Hungary instead of Austria as the European hub for the planned pipeline. According to most experts, Gazprom’s project could kill the EU’s Nabucco because both projects target the same markets.

Moreover, Nabucco is racing against Gazprom to line up supply volumes and markets. Hungary’s separate negotiations with Russia tend to generate uncertainty about Nabucco’s viability and could discourage investment in that project. Gazprom would characteristically impose such long-term arrangements through SEGP that lock the consumer countries in and any competing suppliers out. As part of its tactics, Gazprom even proposes to supply part of Nabucco’s gas volumes — a move that would defeat the EU’s goal to diversify the suppliers to these countries. The Hungarian government’s position directly and indirectly facilitates Gazprom’s tactics.

On some other European issues as well, the Hungarian government’s official discourse has acquired some nuances and emphases that tend to suggest a special understanding of Russia’s positions. I n Sochi, Putin exploited this opening by holding up Hungary as an example to other EU and NATO countries: “While a member of NATO and the EU, Hungary finds the way to promote its national interests through cooperation with others, including Russia … Russian-Hungarian relations can serve as an example in this regard” (Interfax, September 18).

Gyurcsany, one of Hungary’s wealthiest businessmen, has in recent years established his control on the Socialist Party. By filling the foreign affairs minister’s post with a psychologist, Kinga Goencz, who lacks foreign-policy experience, the prime minister essentially controls foreign policy as well. Economics Minister Janos Koka, who runs the negotiations with Gazprom, is also a business tycoon. He leads the Free Democrat Party, junior party in the coalition governmen t. The quality of leadership groups in both parties has deteriorated markedly since the days when they shepherded Hungary’s successful post-communist transition in the 1990s.