Putting Money in the Party’s Mouth: How China Mobilizes Funding for United Front Work

Putting Money in the Party’s Mouth: How China Mobilizes Funding for United Front Work

Introduction

Over the past two years, a series of government and think tank reports have shed light on the united front, the collection of organizations the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leverages to co-opt non-Party institutions and influence minority groups at home and overseas (USCC, August 2018; ASPI, June 2020). Facing heightened scrutiny, People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials have repeatedly insisted that there is “no factual basis” to Western reporting on China’s influence operations, and accused foreign analysts of “maliciously hyping up the normal foreign exchanges of the United Front Work Department” (MFA, June 2020; PRC Embassy in Sweden, August 2019).

However, there is a universal truth known to government bureaucrats in every country: budgets speak louder than words. As this paper demonstrates, the scale and scope of funding for the united front system belie the Chinese government’s claims about its importance and function. This article synthesizes information from more than 160 budget and expense reports from national and regional PRC government and Communist Party entities. [1] It finds that organizations central to China’s national and regional united front systems spent more than $2.6 billion in 2019, exceeding funding for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA, 2020). [2] Nearly $600 million (23 percent) was set aside for offices designed to influence foreigners and overseas Chinese communities.

Defining the Inner Circle of the United Front System

To carry out united front work, the CCP funds a network of dozens of organizations spanning Chinese government, industry, and civil society. United Front Work Departments (UFWDs) of CCP committees at the central, provincial, and local levels of government coordinate activities in each administrative region, municipality, district, or county in China. But amid a tangled web of state, Party, and nominally non-governmental entities, four organizational bureaucracies stand out for their size and importance to united front work. They are each controlled, directly or indirectly, by UFWDs.

- Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conferences (中国人民政治协商会议, Zhongguo Renmin Zhengzhi Xieshang Huiyi or 政协, zhengxie) (CPPCCs) serve as platforms for members of China’s eight minor political parties to participate in Chinese government activities in an advisory capacity. CPPCCs are not official Party or government organizations, but political brokerages controlled indirectly by the UFWD. They are also responsible for recruiting non-Party members to take positions in government, so as to lend credibility to the Chinese political system (Qinghai Municipal UFWD, 2012). The Chinese government frequently points to minority party members in CPPCCs to deflect criticism that China is a one-party state (PRC Embassy in Papua New Guinea, undated). In internal discussions, united front leaders are more blunt: selecting non-Party intellectuals to serve in government preserves the appearance of a “reasonable structure of the leadership team, but also helps expand the Party’s ruling resources and consolidates the Party’s ruling foundation” (Hexi District UFWD, 2017).

- Ethnic and Religious Affairs Commissions (民族宗教事务委员会, Minzu Zongjiao Shiwu Weiyuanhui) (ERACs) formulate and implement the Communist Party’s ethnic and religious policies within China. Specifically, they monitor and censor religious groups banned by Beijing while controlling the appointment of clergy members for sanctioned religious organizations (S. State Department, 2019). In the course of united front work, ERACs “resist religious penetration” of Chinese universities by blocking communication channels for evangelical students and missionary workers (China University of Petroleum UFWD, June 2020). ERACs are government organizations, but they also double as Party entities, sharing the same offices, staff, and budgets as the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureaus of UFWDs. [3]

- Foreign and Overseas Chinese Affairs Offices (外事侨务办公室, Waishi Qiaowu Bangongshi) (FOCAOs) are government offices that coordinate provincial and local Party organizations’ outreach to foreigners and overseas Chinese, especially residents of Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. [4] The united front’s overseas mission is chiefly concerned with promoting the “reunification of the motherland” (Zhejiang Provincial UFWD, 2014). When contacting representatives from the “Three Compatriots” (Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), the united front “actively promotes China’s opening-up policy, introduces preferential policies and procedures for investing in businesses and factories in the mainland, and introduces funds, technology, talents, equipment, and advanced technology…” (CPPCC Work Manual, 2003). FOCAOs coordinate with federations of Chinese students who have returned from overseas study, as well as Chinese student and scholar associations (CSSAs) and Chinese professional associations (CPAs) based abroad (CSET, July 2020).

- Federations of Industry and Commerce (工商业联合会, Gongshangye Lianhehui) (FICs) are nominally non-governmental organizations, which embed Party committees within private enterprises and mobilize Chinese entrepreneurs’ investments in ways that are consistent with the Party’s goals. The constitution of the national All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, for example, stipulates that FICs should “guide members to actively participate in China’s economic construction” and “recommend political arrangements for representatives of the business community” (ACFIC, 1997, pg. 1,229).

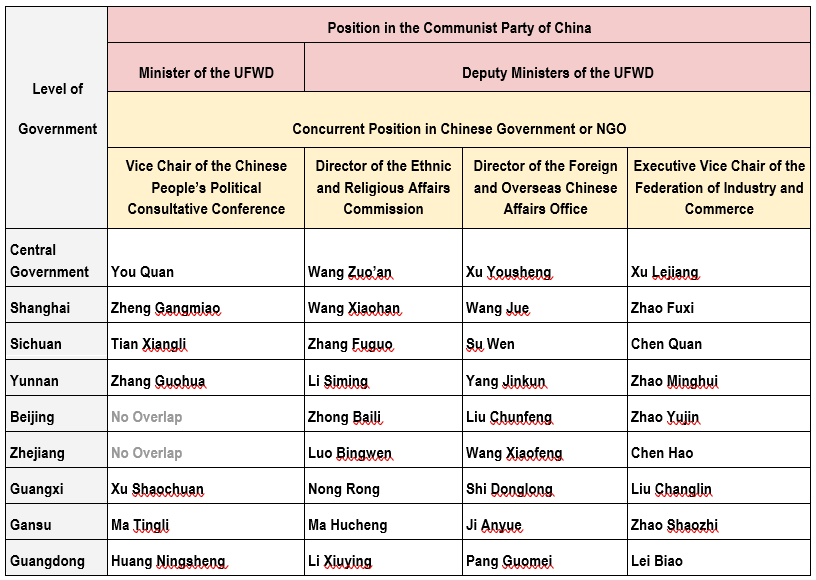

The united front’s control of these organizations is evident at every level of Chinese government. They issue joint press releases, co-host events, and release financial documents simultaneously, sometimes as part of the same spreadsheet or PDF file as that of the local UFWD (Yantian District UFWD, 2018; State Council Press Release, September 2019; Henan Provincial UFWD, 2014; Weihui Municipal UFWD, 2019). But perhaps the clearest signal of their importance to the united front system is found in their overlapping leadership structures—a common practice for key Party figures. The ministers and deputy ministers of UFWDs concurrently serve as the directors and secretaries of party committees within CPPCCs, ERACs, FOCAOs, and FICs, as demonstrated in Table 1. [5]

Table 1. United Front Ministers Hold Concurrent Leadership Positions in Government and NGOs

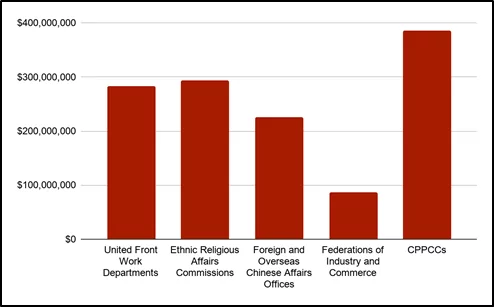

Adding the budgets of these five organizations (UFWDs, CPPCCs, ERACs, FOCAOs, and FICs) is a conservative, if incomplete way to estimate Chinese funding for united front work, including domestic and overseas influence operations. Dozens of smaller organizations not included in this paper, such as federations of overseas returnees, schools of socialism, and Confucius Institutes, are also part of the united front system and report to UFWDs (Foreign Policy, October 2019). Nonetheless, contrasting spending among these five organizations nationally and across each of China’s 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions (a total of 160 organizations) provides a minimum estimate for united front spending, and clarifies the structures and priorities of organizations behind China’s influence operations.

Central Government Spending on United Front Work

The Ministry of Finance publishes annual budget documents for most Chinese government and Communist Party entities, but not the Central UFWD. Budgets are available, however, for the other organizations that form the inner circle of the United front system. [6] Together, their spending amounts to $1.4 billion per year—nearly as much as China’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS, 2019).

Table 2. Yearly Central United Front Spending Tops $1.4 Billion (USD) Per Year

| Entity (English) | Entity (Chinese) | Year Available | Public Budget (USD) |

| Central United Front Work Department | 中央统战部 | N.A. | Not published, likely over $400 million |

| Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference | 中国人民政治协商会议全国委员会 | 2019 | $131 million |

| State Ethnic Affairs Commission | 国家民族事务委员会 | 2019 | $903 million |

| State Administration of Religious Affairs | 国家宗教事务局 | N.A. | Removed |

| Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council | 国务院侨务办公室 | 2017 | $359 million |

| All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce | 中华全国工商业联合会 | 2019 | $19 million |

| Total Budget of the Central Government’s United Front System | At least $1.4 billion, likely more than $1.8 billion | ||

If funding for the Central UFWD mirrors trends in funding at the provincial level, then it likely exceeds $400 million each year. [7] Adding this estimate would bring the central government’s annual spending on united front work to at least $1.8 billion. However, the Central UFWD’s budget is likely much higher. The scope of its mission is broader than that of regional UFWDs: it oversees re-education work in Xinjiang and Tibet, coordinates overseas technology transfer efforts, and is responsible for training the next generation of cadres to fill the ranks of the national Chinese government.

Regional Spending on United Front Work

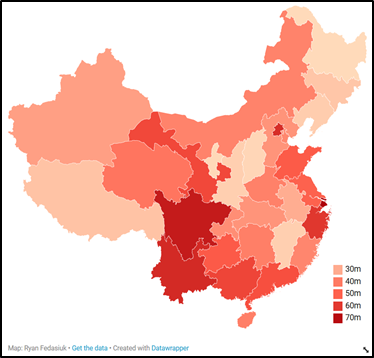

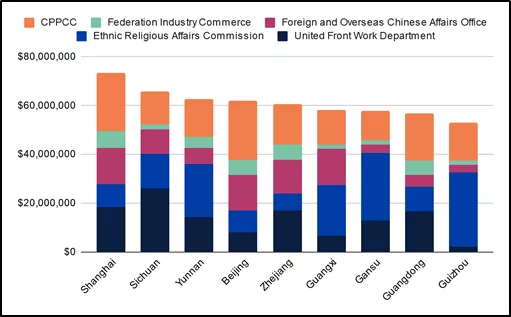

Across China’s 31 administrative regions, spending on united front work exceeds $1.3 billion annually, on par with regional CCP spending on propaganda. CPPCCs spend the most money of any entities in the united front system ($386 million), followed by ERACs ($293 million), UFWDs ($283 million), and FOCAOs ($226 million). FICs have the smallest budgets, amounting to $87 million per year.

Funding for the united front system varies in each administrative region in China, from $21 million in Heilongjiang to $73 million in Shanghai. A mix of wealthy, strategically important areas (Shanghai, Beijing, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Sichuan) and ethnically and religiously diverse areas (Yunnan, Guangxi, Gansu, Guizhou) top the list of regions by spending.

Influence Efforts at Home and Abroad

Ethnic and religious minorities bear the brunt of the united front’s influence efforts inside China. Offices responsible for religious persecution spend upwards of $1.2 billion on related activities each year. Unsurprisingly, the five regions that spend the most on ethnic and religious affairs (Guizhou, Gansu, Yunnan, Guangxi, and Inner Mongolia) tend to have significantly lower populations of Han Chinese and higher populations of ethnic and religious minorities, relative to national averages. ERACs also play a more dominant role in their united front systems; whereas ERACs accounted for 23 percent of united front spending nationwide, in these five regions they accounted for 43 percent—twice the share—of united front spending. Readers might be surprised at how low Xinjiang (20th; $5.2 million) and Tibet (23rd; $4.7 million) rank in ERAC spending. One explanation could be that the Central UFWD has established bureaus dedicated to pouring central government resources into these areas, which likely are not reflected in local budget documents (Guancha News, September 2018).

Foreigners and overseas Chinese are also major targets of the united front. Collectively, the Chinese government equips the central OCAO and regional FOCAOs with $585 million each year. Wealthy coastal regions such as Shanghai, Beijing, Zhejiang, and Shandong dedicate larger shares of funding to their FOCAOs, relative to other regions.

In their day-to-day operations, FOCAOs are responsible for inviting and receiving prominent foreigners in China, training cadres to carry out united front work overseas, and promoting “overseas Chinese-related propaganda” (Zhejiang Provincial UFWD, June 2020; Fengtai District UFWD, January 2019). The budget documents of some FOCAOs also confirm that they coordinate with “national security and intelligence departments” (国家安全及保密部门, guojia anquan ji baomi bumen) to “supervise and inspect the implementation of foreign affairs discipline and foreign-related confidentiality systems” (Jiangxi Provincial FOCAO, February 2019). FOCAOs also coordinate with Chinese student and scholar associations and overseas professional associations to promote “scientific and technological cooperation and talent development” (Fengtai District UFWD, January 2019).

While FOCAOs attempt to influence communities in other countries, they are also responsible for monitoring and censoring what the Chinese government considers to be foreign interference in China. Published in the early 2000s, a 1,700-page instruction manual for the national CPPCC dictated that united front officials should “resolutely oppose any conspiracy to create ‘two Chinas,’ ‘one China, one Taiwan,’ or ‘Taiwanese independence,’” and detailed explicit strategies and tasks the united front should adopt in the Hu Jintao era (CPPCC Work Manual, 2003, Chapter 3). According to more recent Communist Party work committee instruction manuals, many of the same strategies are still deployed under Xi Jinping’s leadership. [8]

Conclusion

Chinese officials maintain that the united front system is a benign network of administrative organizations, and that the PRC’s foreign policy is based on “mutual respect and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs” (PRC Embassy in Sweden, August 2019; ABC, June 2020). If this really were the case, regional governments probably would not classify their united front spending as secret (涉密部门, shemi bufen) or refuse to disclose the structure of government offices ostensibly reserved for public diplomacy (Jiangxi UFWD, February 2018; Jilin FAO, 2020).

At the same time, some Western observers have questioned the importance of the united front system relative to other organizations in China. That regional governments in China budget nearly as much for united front work ($1.3 billion annually) as they do for CCP propaganda indicates how highly the Party values the united front as a tool for both domestic and foreign influence.

Ryan Fedasiuk is a Research Analyst at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). His work focuses on military applications of emerging technologies, and on China’s efforts to acquire foreign technical information.

Notes

[1] In every instance, organizations’ budgets were equal to their spending—a textbook example of the “use it or lose it” nature of government funding.

[2] Budget documents were collected for 2019 or the last year available. About three-quarters of budget figures were from 2019, and all others from 2018. The budget estimates presented in this paper should be considered a floor for United front spending. In reality, funding for China’s United front system is likely much higher. No data is available for the Central United front Work Department, and some regional governments classify details about the organization and spending of organizations involved in United front work as secret.

[3] For example, the budget documents for the ERAC in Shaanxi clarify it is also the Religious Affairs Bureau of the Shaanxi UFWD [陕西省民族事务委员会(省宗教局)2017年部门决算说明], https://archive.vn/0V7UI. Similarly, the Huizhou UFWD website hosts the budget documents of all its constituent organizations, including the Huizhou ERAC/Religious Affairs Bureau [2019年惠州市民族宗教事务局部门预算公开], https://archive.vn/rB7kL.

[4] Whereas deputy ministers of UFWDs previously served as heads of OCAOs in every region of China, they are now starting to serve as directors of the new, broader FOCAOs. For example, see Shi Donglong in Guangxi, “Secretary of the Party Group of the Foreign Affairs Office of the Autonomous Region…” [自治区外事办党组书记…], Foreign Affairs Office of the Guangxi Autonomous Region, July 30, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20200707220528/https://wsb.gxzf.gov.cn/xwyw_48149/szyw_48151/t1701128.shtml; or Zhou Jing in Ruian, “Leading Member of the Foreign Affairs and Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the People’s Government of Ruian City” [瑞安市人民政府外事侨务办公室领导成员], Ruian Government Information Catalogue, June 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20200707220500/https://xxgk.ruian.gov.cn/art/2018/6/7/art_1413231_18475094.html.

[5] Duties assigned to Ethnic and Religious Affairs Commissions are split among two entities at the central government level: the State Ethnic Affairs Commission (SEAC) and the State Administration of Religious Affairs (SARA). Wang Zuoan, Deputy Minister of the Central UFWD, heads SARA. Additionally, in the central government, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs remains separate from the OCAO, which was absorbed into the Central UFWD in 2018.

[6] At the central level of government, SARA is distinct from SEAC. At the regional level, these entities are usually combined into ERACs. However, after it was absorbed into the Central UFWD, SARA removed any trace of its budget documents from its website.

[7] On average, the local UFWD accounts for only about 22 percent of spending on the broader united front system in each province or region.

[8] See example strategies and guidance for carrying out united front work in “Peking University Party Branch Work Instruction Manual (Draft for Comment)” [北京大学党支部工作指导手册 (征求意见稿)], December 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20200707231607/https://student.coe.pku.edu.cn/docs/2019-08/20190823134035407054.pdf.