Revision of Montreux Convention Could Work in Moscow’s Favor

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 22

By:

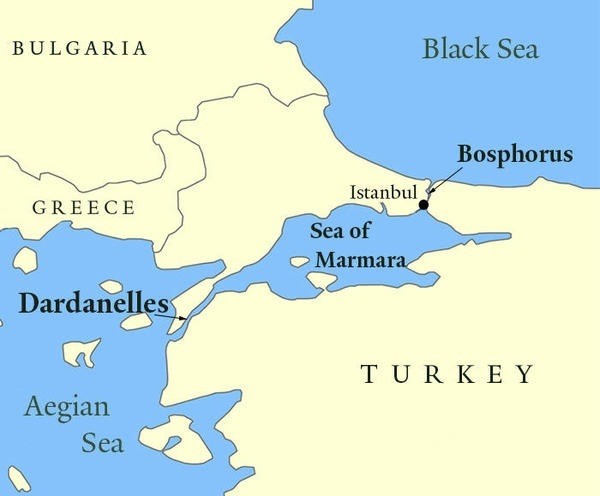

The 1936 Montreux Convention governs the passage of ships between the Mediterranean and Black seas via the Turkish Straits, dictates the size of the vessels that can remain there, as well as limits how long they are allowed to stay. Now, 85 years later, this influential treaty is likely to be revised, Moscow military analyst Sergey Marzhetsky says, when Turkey completes its new Istanbul Canal, which will allow ships to bypass the northern element of the Straits—the Bosporus (although not the Dardanelles). But despite the fears of many in Russia, it is highly unlikely there will be any revision in the Convention without Turkey’s approval or that such changes will benefit the West at Russia’s expense. Instead, he argues, Ankara’s own ambitions are such that they may lead to modifications of Montreux that actually advantage the Russian Federation more than Turkey’s North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies. The reasons for that, Marzhetsky suggests in two new articles, lie in Turkey’s own longer-term interests and the ways in which these conflict with Western goals (Topcor.ru, January 27, February 8).

The 1936 accord specifies that civilian ships from countries without a Black Sea littoral have the free right of passage through the Turkish Straits both in times of peace and times of war. But military ships of non-littoral states can be present in the Black Sea only in peacetime, for a limited period, usually 21 days, and with a specific tonnage, lower than many of the largest ships in the NATO fleets. In recent years, the Western alliance has rotated ships through the Straits into the Black Sea on a regular basis to maintain a presence and project power, but it has not been able to insert its largest vessels or submarines. The presence of Western navies in the Black Sea has been a constant irritant for Moscow; consequently, the Russian government has sometimes favored a revision of Montreux that would eliminate them, and other times, it backed this long-standing convention as the best way for Russia to constrain the unwelcome Western presence (see EDM, April 2, 2019, April 23, 2019, October 1, 2019).

Two developments have exacerbated Moscow’s concerns about Montreux in recent months, Marzhetsky says. On the one hand, Ankara is seeking to build a canal that would allow ships to transit between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea without passing through part of the Straits. Such a canal could vitiate Montreux, he argues, even though Russian officials have insisted that Montreux’s restrictions would apply to ships using the Istanbul Canal as well. And on the other hand, he points out, Ankara is pursuing a dramatic expansion in its navy. It already has the second-largest army in NATO; and it clearly wants to have a major fleet as well, one with a full-sized aircraft carrier—it is currently constructing a small one. This would allow it to project greater power not only in the Eastern Mediterranean but in the Black Sea as well (Topcor.ru, January 27, February 8).

The Russian ambassador in Ankara has insisted that the Montreux limits will survive the construction of the Istanbul Canal and apply with equal force to ships using that waterway as ones passing through the Bosporus. But the Russian military analyst counters that “this is not entirely so,” because while the appearance of the new canal will not affect the Montreux rules, it will give the Turkish government an opportunity to “raise the question about the review of the provisions of that international legal document” and argue that it no longer “corresponds to contemporary realities.” If Ankara were simply an agent of Washington, as some Russians think, that could lead to a situation in which the United States would be able to put more and larger naval vessels into the Black Sea for longer and longer periods or perhaps without any limitations at all. But Turkey is not a US proxy, Marzhetsky writes; therefore, any revisions Ankara may propose or agree to will work to its benefit and not necessarily for its Western allies.

Ankara sees no advantage to a larger presence in the Black Sea (or the Eastern Mediterranean) of ships from the US, the United Kingdom or France. They would only encumber Turkey’s aspirations to be the dominant player in the region. What this means, the Russian analyst predicts, is that “Turkey will solely seek to exclude from the [Montreux Convention] limits the passage through its Straits of aircraft carriers not carrying nuclear weapons.” That way, Turkey could freely send its aircraft carriers and possibly also submarines into the Black Sea; but the US, the UK and France could not. Thus, Washington, London and Paris would not be beneficiaries from any change, and Moscow would not be a big loser, Marzhetsky says. In fact, it could be a beneficiary because its civilian fleet would be able to make use of the new canal, avoiding the crowded Bosporus route.

“In other words,” the Russian military analyst contends, “if Turkey does revise Montreux, it will do so to its own benefit” and no one else’s. Those treaty modifications will not be all that welcome in Russia on principle, but the results will certainly not be the tragedy some are suggesting. And that gives Moscow the opportunity to side with Turkey against the West on revising the 1936 convention, something that Turkey will welcome and that will help to further distance Ankara from Western capitals—yet another development Moscow can profit from. If others in Moscow accept this argument, it could mean the Kremlin will now ally itself with Ankara on this issue. Such a move could create new problems and tensions within the transatlantic alliance.