Russia and China Part Company in Davos

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 14 Issue: 5

By:

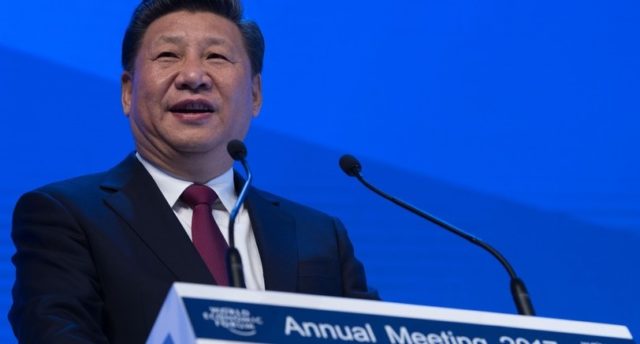

Chinese President Xi Jinping was this year’s star guest at the World Economic Forum in Davos (January 17–20), where the mood of the traditional crowd of successful entrepreneurs and high-flying politicians was far from jubilant. The shadow of the inauguration of US President Donald Trump was so dark that Anatoly Chubais, one of Russia’s veteran reformers who still try to connect with the global elite, described the atmosphere in the Swiss resort as “deep dread” (BFM, January 19). Xi, to the contrary, radiated confidence and enjoyed the sincere admiration of the moneyed audience, which was entirely unconcerned about such topics as human rights in China. Russian President Vladimir Putin had no intention of traveling to Davos this time, and did not even think about dispatching his usual substitute, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. The obstacle for the Kremlin was not the dismal performance of the Russian economy, but the country’s profound incompatibility with the kind of globalization that Davos has come to exemplify (Moscow Echo, January 18).

Perfectly at ease with his debut performance at Davos, Xi started his address with a quote from Charles Dickens about “the best of times and the worst of times.” The Chinese leader stated in no uncertain terms that his country was ready to take the lead in sustaining the dynamics of global growth (Kommersant, January 20). He preached to the liberal-minded crowd about the benefits of free trade and condemned protectionism, positioning himself at the forefront of an effort to turn the tide of populist parochialism around the world (Vedomosti, January 19). Asserting his commitment to economic openness, he implied that China did not fear trade wars with the newly-isolationist United States, which is turning away from the negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—the massive multilateral regional trade deal that could have contained China’s expansion (RBC, January 17). He announced a new step forward in his “One Belt, OneRoad” initiative but refrained from addressing such sources of regional instability as North Korea (which seems to be preparing yet another nuclear test) or the South China Sea. The Chinese president concluded on a remarkably positive note about history being “created by the brave” (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, January 18).

Xi did not find it opportune to mention Russia even once in his address. This conscious omission reflects the fact, often obscured by layers of self-complimentary rhetoric, that China’s bilateral strategic partnership with Russia simply does not fit into the model of dynamic globalization that Beijing is promoting. At Davos, outgoing US Vice President Joe Biden stated that “Russia has a different vision for the future,” which underpins Moscow’s aim “to collapse the liberal international order.” Biden further discussed the implications of Russia’s international maneuverings at a face-to-face meeting with Xi on the sidelines of the Forum (Newsru.com, January 18). Russia is indeed actively and massively deploying “hybrid” weapons of propaganda, corruption and cyber-crime against the West (Gazeta.ru, January 18). Two thirds of Russians (rather than 80 percent a year ago) now think that the country faces enemies on the international arena, but as many as 75 percent of respondents take pride in the belief that Russia is feared by its neighbors (Levada.ru, January 16).

China, on the other hand, seeks to reassure its partners—though not always successfully—that they have nothing to fear from its peaceful rise. Beijing now has an opportunity to claim the role of a guarantor of the stable evolution of the international order. Whereas Russia continues its full-blown assault on this order by targeting particularly the turbulent Middle East. It has recently joined forces with Turkey in combat operations in northern Syria, treating the Kurdish forces as hostile rebels on par with the Islamic State (Novaya Gazeta, January 19). At the same time, Moscow has launched a new format for Syrian peace talks—a conference in Astana, Kazakhstan, co-sponsored with Iran and Turkey, but with no Western contribution (RBC, January 20). In a parallel intrigue, Moscow hosted a meeting between Hamas and Fatah, where yet another agreement on forming a Palestinian national unity government was penciled. This meeting was supposed to convince Israel that Russia is a key party to the talks on the impossible but inescapable two-state solution (Gazeta.ru, January 15).

China remains suspicious of Russian attempts to exploit the US’s retreat from the Middle East: For instance, Khalifa Haftar—the self-appointed “marshal” of the rebel forces in Benghazi who challenges the Libyan government in Tripoli—was recently welcomed onboard the Russian aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov, on its way back to Severomorsk from the eastern Mediterranean (Svobodnaya Pressa, January 12). Beijing is also far from thrilled by Russia’s agreement with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) on cuts in oil production to push the price up, amounting to a cartel colluding against free trade—which Xi so powerfully promoted in Davos (Forbes.ru, January 18).

Yet, the strongest force contributing to the growing political divergence between Russia and China is their contradictory economic performance. Despite a recent worrisome slowdown, China continues to prioritize growth and remains the main beneficiary of Davos-style globalization (Rossiiskaya Gazeta, January 21). Russia, meanwhile, is stuck in stagnation, and its attempts to lure Asian investors with promises of a return to modest growth in 2017 are as ineffectual as Moscow’s attempts to persuade the European Union to lift its sanctions (Kommersant, January 19).

With the limits of the Russian-Chinese strategic partnership becoming clearer and the relationship slipping ever lower, Putin is pinning his best hopes on the incoming Trump administration’s apparent mixture of arrogant unilateralism and narrow-minded isolationism. Nobody from the Trump transition team was present at Davos; and if their boss’s Twitter account gives any indication of the new US administration’s policy guidelines, they indeed would have had no business there. But this does not necessarily determine that a US rapprochement with the anti-globalist and maverick Russia is in the cards, and the Kremlin is now downplaying its expectations of a “beautiful friendship” (RBC, January 20). Indeed, Moscow may soon discover that its best opportunities for both cooperating with Washington and for taking advantage of US reluctance to becoming entangled in new messy conflicts abroad opened and closed during Barack Obama’s just-concluded presidency (Vedomosti, January 20). China has to expect many test of wills in its relations with the US, but Xi needs no help from Putin to manage these challenges. What he expects from Russia is for it stay on an even keel and refrain from high-risk experiments in projecting its diminishing power. But such expectations are unlikely to come true.