Russia Hopes to Use Caspian Sea Route to Evade Sanctions

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 35

By:

Executive Summary:

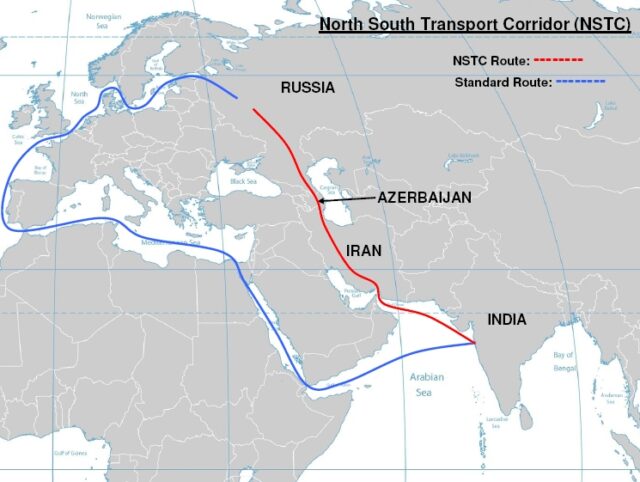

- Moscow seeks to boost its struggling economy through increased development of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) as a real competitor to the Suez Canal and the Bosphorus Strait.

- Moscow wants the INSTC to open pathways to new markets that circumvent Western monitoring and sanctions to better sustain its war-time economy.

- Infrastructure development along the INSTC remains meager, an issue that will soon require serious modernization, but the Kremlin sees long-term potential in developing this economic corridor.

On February 26, Serik Zhumangarin, Kazakhstan’s deputy prime minister and minister of Trade and Integration, called for increased transit along the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route. That shift may serve to boost business and economic ties with Russia, Iran, Turkmenistan, and other regional players (Inform.kz, February 26). Although Kazakhstan has its own reasons for supporting routes that avoid Russia, Moscow may be looking to exploit such developments to evade sanctions and access other markets away from Western eyes. The INSTC is a 7,200-kilometer-long ship, rail, and road route for moving freight between India, Iran, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Central Asia and could provide a means for the Kremlin to reassert its influence over regional transit and trade.

The idea of a trade corridor between Russia and South Asia goes back to the 15th century to the famous voyage of a merchant from Tver, Afanasy Nikitin. From 1889 to 1892, Russian engineers devised plans to build a water artery to Iran and India. During Soviet times, the Caspian Sea was used to transport military equipment and materials as a part of the Lend-Lease Act. After World War II, the idea of building a major transportation route was tabled for a time (Flagman-news.ru, June 26, 2023).

Notable changes occurred in 1999 when the agreement to create the INSTC was signed between Russia, Iran, and India. This development was largely a by-product of the actions of Yevgeny Primakov, at the time, the anti-Western premier, a Russian conservative, and strong proponent of the India-Russia-China triangle. Later, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Syria, Oman, and Bulgaria (as an observer) joined the agreement. These moves were mostly symbolic and did not contribute much to substantive development along the INSTC (Kommersant.ru, November 30, 2021). The situation began to change more drastically after the April 2021 incident in the Suez Canal when transportation along the world’s busiest transportation artery was essentially paralyzed. Specifically, the INSTC experienced visible growth in railroad container transportation in 2022 (Interaffairs.ru, July 26, 2022).

Multiple problems instantly became evident—including the lack of sea-based infrastructure between Russia and Iran and the unsatisfactory state of Russia’s seaports—stunting any real increase in transportation and trade ties. The initial failure, however, did not dissuade the Kremlin from continuing to foster support for the INSTC’s development. For example, Russian experts note that, if technical issues are dealt with expeditiously, the INSTC could provide Russia with the shortest (between 15 and 25 days instead of 45) and cheapest (by 30 percent) possible trade route to the markets of Pakistan, India, and other countries in Southeast Asia. Other experts have argued that the INSTC could become a real competitor to the Suez Canal and the Bosphorus Strait (Ng.ru, December 22, 2022).

Moscow sees numerous benefits in the further development of the INSTC. First, the route would provide a bridge for Russia to the Global South (primarily, the countries of the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia). The Kremlin’s emphasis on this transit corridor highlights Russia’s pivot to the Indo-Pacific. Many Russian experts compare the INSTC to the gas- and oil-pipeline networks to Europe, which played a vital role in the Moscow’s ability to divert hydrocarbons to European markets and the Trans-Siberian Railway (Transsib) and Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM). Increased use of these routes paved the way for increased economic cooperation with China and Northern Asia. Russian analysts have claimed that the project could offer a historic chance for the Eurasian Economic Union to extend Russia’s economic presence in the booming markets of the Indo-Pacific region and beyond (Eurasia.today, August 16, 2023).

Second, the INSTC would strengthen the development of intra-Caspian ties in the format of the “Caspian Five”—Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Such an arrangement would give Moscow increased influence over Caspian trade and allow Moscow to redirect its economic and geopolitical aims toward the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. That reorientation will likely diminish Russia’s strategic connection to the ports of the Black Sea and Azov Sea basins. In terms of its economic-industrial core, Russia will be able to accomplish a strategic shift from the “Ukraine pre-borderland” (along the so-called Federal Automobile Road M-4 “Don”) closer to the Volga basin area (Eurasia.today, August 16, 2023).

Third, the INSTC has the strong potential to revitalize the economies of several Russian regions. The Astrakhan region (and the city of Astrakhan) would likely be the primary beneficiary. According to Astrakhan Governor Igor Babushkin, last year, the region witnessed a dramatic increase in cargo transportation, by 70 percent as compared to 2022. Additionally, exports increased by 77 percent and imports by 44 percent. Alexander Tysiachnikov, a Russian consultant on marine transit, noted that, after the outbreak of the so-called “special military operation,” many Western companies abandoned the Russian market, primarily disrupting cargo transit in the Baltic Sea region, dropping by 75 percent, and the Black Sea region, which experienced a 40 to 45 percent drop. In contrast, freight transportation in the Caspian Sea region has steadily grown in recent months (Ng.ru, January 15, 2024).

Russian experts point to three critical challenges hindering the INSTC’s successful development (Flagman-news.ru, June 26, 2023). First, Moscow does not possess enough vessels on the Caspian Sea to secure constant and uninterrupted transportation of massive volumes of freight, one of the fundamental pillars of economies of scale.

Second, Russia lacks appropriate infrastructure, including sufficiently deep canals and arteries for the passage of large cargo vessels. The infrastructure issue is not a new challenge. Its origins go back to Soviet times when river ports were built in city centers, tying all transportation to inner-city infrastructure. As the infrastructure has become more decrepit and, in many ways, no longer suitable for cargo, the whole system warrants serious modernization.

For now, the actual changes in the development of infrastructure along the INSTC remains meager. However, with Russia’s departure from the West and prospective greater integration with the Indo-Pacific region, Moscow could obtain a significant competitive advantage, in which it begins to control larger parts of north-south transit routes.