Russia Lacks ‘International’ Factor in Preparations For 6th International Arctic Forum

Russia Lacks ‘International’ Factor in Preparations For 6th International Arctic Forum

Executive Summary:

- Moscow is attempting to signal its leadership of Arctic affairs with the sixth meeting of the International Arctic Forum (IAF) on March 26–27.

- As Russia continues its war against Ukraine, the planned IAF program reflects Moscow’s isolation from most international Arctic partnerships, while the People’s Republic of China remains the most attractive partner in Arctic cooperation.

- Moscow’s narratives during and after the 2025 IAF will indicate any potential shifts in Russia’s perceived status as the leader in Arctic affairs and the degree to which it may interpret the activities of other states in the High North as competitive with that status.

On March 26–27, the sixth meeting of the International Arctic Forum (IAF) convened by Russia will occur in Murmansk (IAF, accessed March 20). In advance of the IAF, Russian President Vladimir Putin recently claimed that Russia is “committed to cooperation with all interested partner states and integration associations” (President of Russia, March 17). The upcoming IAF signifies Moscow’s goal to be at the forefront of Arctic affairs and cooperation and innovation in the region, while challenges remain given Russia’s international isolation due to its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Thus far, these challenges appear to be causing Moscow to struggle in attracting international participation for the IAF, instead relying on domestic engagement and attendance.

Moscow remains committed to its goal of maintaining “Russia’s leadership in the Arctic and [ensuring] dynamic economic development of this macro-region [by consolidating] all available tools, including financial and managerial” (President of Russia, February 28). One of these tools is the IAF, which, for the first time, will be held in Murmansk. The IAF has previously taken place in Moscow (2010), Arkhangelsk (2011 and 2017), Salekhard (2013), and St. Petersburg (2019). Of these cities, Salekhard is the only one located in the Arctic. Murmansk is a notable location as Russia’s westernmost Arctic city near the border with Finland and Norway and, according to Putin, “Russia’s gateway to the Arctic” (President of Russia, March 17).

Moscow’s international relations, however, have seismically changed since the last IAF in 2019 with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Finland and Sweden have joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (NATO, April 4, 2023, March 7, 2024). Greenland has become a point of renewed security interests for the United States (see Strategic Snapshot, February 10). Meanwhile, Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Finland, Norway, and Sweden have all joined in support of Ukraine in Russia’s ongoing war against the country (Government of Canada; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland; Government of Iceland; Government of Norway; Government Offices of Sweden, accessed March 17). Another consequence of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine was the rejection by the seven other Arctic states of cooperation with Russia in the Arctic Council in March 2022, which has since resumed limited project-level work (High North News, April 27, 2022; Arctic Council, February 28, 2024). Additionally, cooperation with Russia in the Barents Euro-Arctic Council was suspended in March 2022, and, in 2023, Russia withdrew from the Council (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, May 17, 2022, September 18, 2023). Moscow has also withdrawn from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) and it no longer cooperates with the Nordic Council of Ministers (Nordic Council, March 3, 2022, February 25; ICES, February 28). Additionally, the European Union, Iceland, and Norway have suspended cooperation with Russia and Belarus in the Northern Dimension joint policy (Koivurova, et. al., 2022; European Union, March 8, 2022; ICES, February 28).

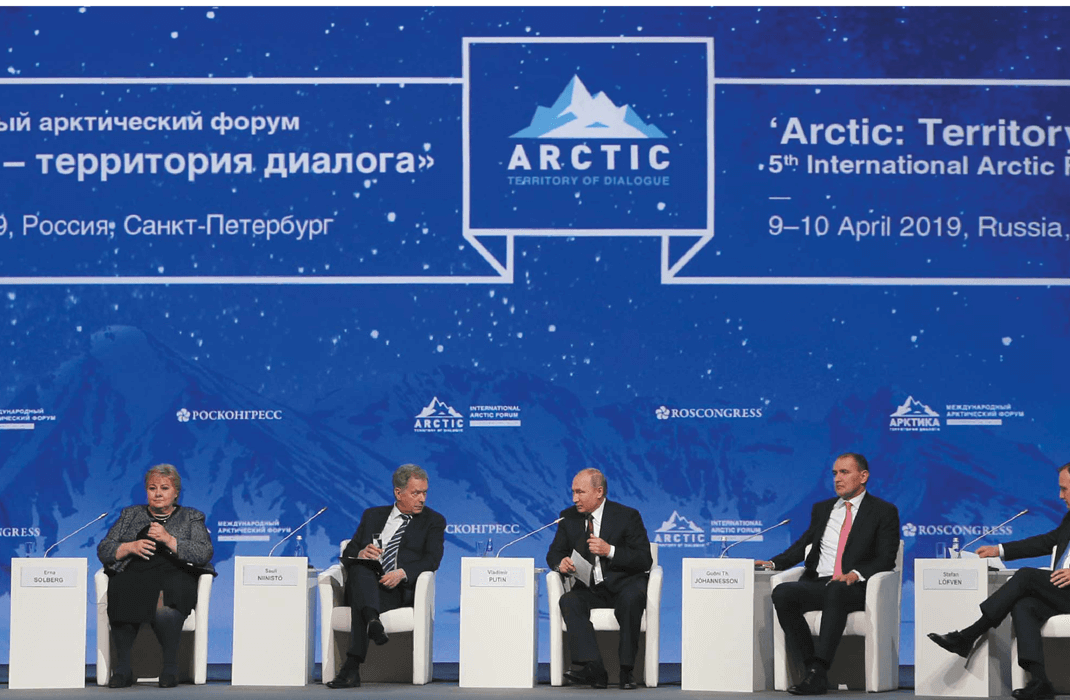

Prior to these substantive changes in Arctic cooperation, in 2019, the presidents of Finland and Iceland, the prime ministers of Norway and Sweden, and the foreign ministers of Denmark and Norway attended the IAF (IAF, accessed March 17). The website of the IAF claims that the largest delegations were from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Norway, Finland, Sweden, the United States, Denmark, Iceland, Canada, and Japan (IAF, accessed March 17). It was also attended by representatives from 12 international companies along with 129 representatives of Russian companies.

Putin has attended all of the past IAF meetings, and it would therefore be unusual if he is absent for this one. On March 17, he issued a welcome statement, as he has done in the past, to the government officials, scientists, and experts who will be in attendance (IAF, April 8, 2019; President of Russia, March 17). Unlike in previous years, the attendees have not been officially announced (President of Russia; IAF, April 1, 2019). The only international representatives in the program thus far are from the PRC, Iran, and Japan. These are Ke Jin, General Director of China Freight Forwarding Company, Hanieh Moghani, Vice-Chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and Sakiko Hataya from Japan’s Sasakawa Peace Foundation (IAF, March 17; UN Decade; Sasakawa Peace Foundation, accessed March 18). Additionally, Lily Ong, a geopolitics talk show host in Singapore, is noted as a “front row participant” (IAF, March 17; Geopolitics360.net, accessed March 18). Other speakers and attendees include Kremlin advisers and ministers, Duma representatives, regional governors, and heads of Russian corporations such as Rosatom (which is sponsoring the IAF), Novatek, the Far East and Arctic Development Corporation, Norilsk Nickel mining company, among others (IAF, March 17, [1], [2]).

As in prior years, the 2025 IAF features a cultural program to showcase “the uniqueness and achievements of the Arctic regions, as well as Russia’s leading role in the development of the Arctic,” according to Anton Kobyakov, advisor to Putin and Executive Secretary of the IAF Organizing Committee (Investment Platform of Russian Regions, March 10). The cultural program includes a tour of the Soviet-era Lenin nuclear-powered icebreaker (the first in the world, as well as the first nuclear-powered civilian vessel) (IAF, accessed March 17). It also features a series of sporting events, including the 51st Murmansk Ski Marathon, which attracted participants from Germany, Slovakia, Australia, Georgia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan in 2019 (IAF, accessed March 18).

The isolating developments discussed above have left Russia with a short list of potential Arctic partners with whom it can cooperate despite the barrage of planned activities. Currently, the PRC is the most attractive partner in terms of its interests and availability to engage in the Arctic (see EDM, February 18, March 6). The PRC has held observer status in the Arctic Council since 2013 (Arctic Council, accessed March 17). Additionally, in 2018, the PRC declared itself a “Near-Arctic State,” marking a new type of identity in what it means for states to be Arctic (State Council of the PRC, January 2018).

The most notable agreements and new cooperation initiatives resulting from the 2019 IAF were with the PRC (IAF, April 10, 2019). In April 2019, an agreement was signed between the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Qingdao National Laboratory on the intended establishment of the China-Russia Arctic Research Center (Ocean.ru, April 10, 2019). A few days later, the PRC’s National Oil and Gas Exploration Development Company and Russia’s Novatek signed a framework agreement to develop the Arctic LNG 2 project (CNPC, April 26, 2019; see EDM, May 20, 2019; Novatek, accessed March 17). Russian and PRC representatives are, therefore, likely to announce further collaboration agreements at this year’s IAF.

Potential further cooperation agreements between Russia and possible attendees of this year’s IAF may include transportation and infrastructure partnerships with states such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. This was highlighted in February as a point of discussion for the IAF in relation to the Northern Sea Route (NSR) during a meeting of these states and Russia at the 3rd Caspian Economic Forum in Tehran (IAF, accessed March 17).

Engagement excluding other Arctic states would mark a shift for the IAF. Most agreements produced from the IAF tend to be between domestic partners, but in the past, the Forum has been a platform for international dialogue and cooperation between Russia and High North neighbors. At the 2019 IAF, Putin met with a number of state leaders, including Patricia Espinosa, then-Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Erna Solberg, then-Prime Minister of Norway, Stefan Löfven, then-Prime Minister of Sweden, Sauli Niinistö, then-President of Finland, and Gudni Thorlacius Johannesson, then-President of Iceland (President of Russia April 9, [1], [2], [3], [4], [10], 2019). The 2019 IAF also featured an Arctic fishing industry discussion with state representatives and subject matter experts from Russia, Norway, Iceland, Japan, and the United States (IAF, April 10, 2019). One month prior, an EU agreement on preventing unregulated commercial fishing in the Arctic had been signed by Canada, the PRC, Denmark, Iceland, Japan, South Korea, Norway, Russia, and the United States, which entered into force later that June (European Union, March 18, 2019; European Commission, June 25, 2019). Also in 2019, the Arctic Society of Finland signed an agreement with the Russian Geographical Society on scientific and cultural collaboration (IAF, April 11, 2019).

Given recent developments, this year’s IAF will likely feature heavy domestic attendance and much lighter international participation than in years prior. At this point, the upcoming IAF may as well be called the Domestic Arctic Forum. Ultimately, the most revealing aspect of this year’s IAF will be which and how many international representatives choose to attend. As narratives about past IAFs emphasize the number of participants and the degree of international participation, it will be important to observe any shifts that might occur in how the 2025 IAF is portrayed. This may in turn signal potential loss of Russia’s own status as the claimed leader in the Arctic and alter how Moscow perceives the presence of other states as competitive with its own position in the High North.