Russian Report Questions Missile Defense Myths

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 126

By:

The continued standoff and potential risk to US-Russian bilateral relations over the Obama administration’s missile defense plans were recently underscored by Chief of the General Staff, Army-General Nikolai Makarov who stated that “no progress” has been made in ongoing negotiations. On June 28, Makarov explained that this lack of progress has occurred against a background of “useful” discussions on the issues involved in missile defense, but this had been followed in May 2012 by the NATO summit in Chicago, marking the approval of the first stage of deploying the system in Europe (Interfax, June 28).

One day earlier, while generally advocating continued dialogue on missile defense between NATO and Russia, officials in Brussels expressed concern that Moscow’s repeated statements about possible “counter measures” in response to the deployment in Europe of a US and NATO missile defense shield did not facilitate a real discussion of the problems (Interfax, June 27). However, the nature of Russian security concerns about the theoretical risk from missile defense to the long-term strategic nuclear balance, and in particular to its own nuclear deterrent, is well known.

Curiously this political stance is openly questioned by the Russian military-scientific community. In an article in Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye on June 8, the content and conclusions of a recently published report on missile defense and the legacy of the US withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty contradicted the official position of the Russian government. The report, published by the USA and Canada Institute in Moscow, has impressive credentials: its authors are Sergei Rogov, the Director of the institute, and its Deputy Director Major-General (retired) Pavel Zolotaryev, Colonel-General (retired) Viktor Yesin, the former Chief of the main staff of the Strategic Missile Troops (RVSN) (1994-1996) and Vice Admiral Valentin Kuznetsov, Russia’s Chief military representative at NATO (2002-2008) (https://nvo.ng.ru/concepts/2012-06-08/1_dogovor.html).

The report was published to mark the tenth anniversary of the decision by the then US President George W. Bush to abrogate the 1972 ABM Treaty, referred to by the authors as a cornerstone of strategic stability, and it also noted the recent context of Moscow staging an international conference on missile defense in May 2012. The article about the report focused on presenting a detailed overview that reflected on the implications of the “ABM problem.” However, at the outset, the authors refer to the discussion as often being “incomplete” and restricted to “propaganda myths and stereotypes.” They frame the analysis that follows by noting the prevailing “alarmist assessments” and “excessive exaggeration” of the military-technical capabilities of the US missile defense system and the actual future risk it poses to Russia’s nuclear deterrent. The report states that Moscow already possesses assets to overcome the missile defense shield, and that many assessments of the system are rooted in “worst case scenario” approaches (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, June 8).

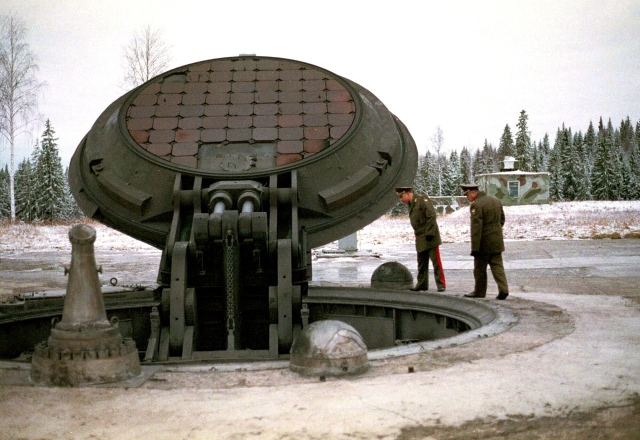

The report is clear in its main assertion: The US strategic missile defense system will not, in the foreseeable future, jeopardize Russia’s strategic nuclear forces. The report states: “The US strategic ABM system has only a ground-based intercept [GBI] echelon with limited capabilities (20 GBI interceptors in two positional regions). The current American strategic ABM system can intercept several primitive ICBMs [Inter Continental Ballistic Missiles] if the attacking side does not employ assets that counter anti-missile defense (maneuvering during flight, using false targets, jamming information systems, etc). The US strategic interceptors have never been tested against an ICBM. Tests have been conducted only in intercepting medium-range missiles, and only for a predetermined time and a predetermined and known flight trajectory. There has not yet been a single successful intercept in conditions where an enemy has launched false targets” (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, June 8).

The justifications for reaching such conclusions are based upon a thorough consideration of the technical and design constraints in the US missile defense system. One instance of this approach is to note that the system currently under development and aimed at full deployment in Europe at the start of the next decade, does not offer any solution to the problem of distinguishing between false targets and actual warheads in the mid-sector of the missile’s flight; whereas a whole complex of anti-missile defense is installed in the warheads of Russian ICBMs. On the military-technical challenges facing US missile defense, the report highlights the likelihood of deploying space-based platforms to be limited until around 2025 at the earliest. The success of the “Aegis” system is acknowledged by the report’s authors, which provides a capability against short and medium range ballistic missiles. However, the speed of the interceptors in the Standard Missile (SM-2 and SM-3 block 1) does not exceed 3.5 kilometers (km) per second making it impossible to intercept an ICBM in mid-sector trajectory. Moreover, these speed characteristics also pertain to the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) ground-based missile defense system, which simply poses no threat to ICBMs (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, June 8).

Indeed, the authors highlight many of the complex technical characteristics of missile defense including unresolved software issues:

“At the end of the current and the beginning of the next decade, there is a plan to commence the deployment of the SM-3 Block 2B interceptor, whose speed is to be 5.5 km per second. For now there is not even a preliminary design for such an anti-missile. The creation of the SM-3 Block 2B, which is to have both liquid-fuel and solid-fuel stages, requires the solution of complicated technical tasks that will not occur before 2020. If this happens, the US will have a new generation strategic anti-missile, whose cost will be four to five times less than the cost of the present GBI systems. However, it is possible that the SM-3 Block 2B will share the same fate as the other high-speed kinetic energy interceptor (KEI), which was intended for the interception of ICBMs in the final and middle sectors of flight; work on it was stopped by the Obama Administration in 2009” (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, June 8).

The report outlines the European Staged Adaptive Approach to missile defense, which prioritizes the deployment of various modifications of the SM-3 anti-missile. The first stage was completed in 2011. The Monterey naval cruiser is on operational watch in the Mediterranean Sea, equipped with the Aegis system using SM-3 Block 1A anti-missiles, and radar has been installed in Turkey and a control center in Germany. During the NATO Summit in Chicago in May 2012, the Alliance declared that the “intermediate system” of European missile defense is now operational. The second stage, scheduled for completion in 2015, will deploy 24 SM-3 Block 1B interceptors in Romania and transfer four destroyers equipped with Aegis to the Rota naval base in Spain. The third stage will deploy 24 ground-based SM-3 Block 2A interceptors in Poland by 2020, while the fourth stage will re-equip European missile defense bases with SM-3 Block 2B interceptors by 2020; these are intended to intercept ICBMs in their final sector (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, June 8).

The technical parameters of the SM-3 Block 2B are still to be announced, but the report pointed to another Russian expert assessment in April 2012, which concluded that although the “potential capabilities” of missile defense are great, accomplishing the interception of one missile would require between five to ten anti-missiles (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, April 13). For this reason, the report concludes: “Until at least 2020 this system cannot have any meaningful effect upon reducing the potential of Russia’s Strategic Nuclear Forces, which are now undergoing a substantial modernization” (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, June 8).