Russia’s Aerospace Defense Forces: Organizational Chaos

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 154

By:

Recent specialist commentaries in the Russian military press indicate deep dissatisfaction with the Aerospace Defense Forces (Vozdushno-Kosmicheskaia Oborona—VKO) created in December 2011. The complexity of the new structure is not only openly criticized, but there are growing calls for its reorganization in addition to brigade commanders expressing negative views on a range of issues including personnel in the VKO brigades (Ekho Moskvy, August 19).

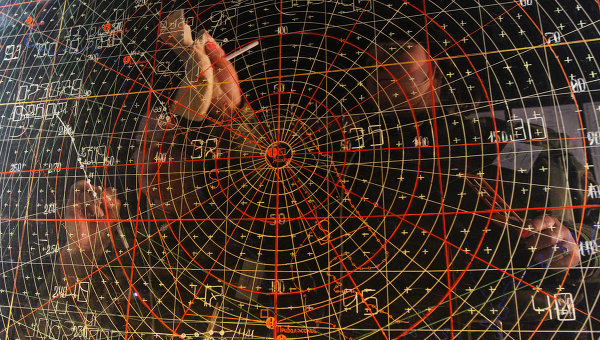

Aleksandr Tarnayev, a member of the State Duma Defense Committee, penned a lengthy critique of the VKO in Voyenno Promyshlennyy Kuryer. Tarnayev reminds his readers that the VKO was established in December 2011 as a new combat arm to organize combat operations among groups of forces in different branches into an overall system of armed conflict placed under a single leadership, as well as a single concept and plan. Yet, due to insufficient rights transferred to the new force structure, the VKO command, according to Tarnayev, cannot fulfill its role. The General Staff lacks the elements needed to constantly track the aerospace situation, re-equipping the VKO with modern high technology assets is progressing too slowly, while the unified system of air defense in the country was broken into five parts: four air defense military districts and VKO force elements (https://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/17139).

The roots of the organizational complexity involved in the creation of the VKO lies in combining a portion of air defense and missile-space forces and assets, which were intended to develop methods of joint command and control. It is precisely this fusion that has failed to happen. According to experts, this failure lies in the absence of a strategic command element, with its duties and rights to organize combat operations among groups of forces, including differing branches and arms of service, in-fighting over command control, the departure of specialists with an understanding of the VKO structure, as well as other issues. In short, Tarnayev states that Russian military specialists believe that the VKO has thus far failed to unite existing subsystems into a single overall system of aerospace defense (https://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/17139).

Tarnayev’s gloomy picture concerning the organizational mess that has unfolded within the VKO is supported in an article by Professor Vladimir Barvinenko in Vozdushno-Kosmicheskaya Oborona. Barvinenko suggests that a new statute must be drafted on the issue of coordination within the VKO. He arrives at this conclusion after referring to work on similar drafts by specialists in the air defense academy (now rebranded as the aerospace defense academy). Though, after these experts worked on this process for fifteen years, it was never published. The author consequently argues that a new statute must be drafted to cover the VKO, taking into account the reorganization of air defense corps and divisions into VKO brigades, with their fighter aviation removed from these air defense brigades. Indeed, Barvinenko concludes that questions of organizing and maintaining VKO coordination and “ensuring the safety of friendly aviation” must be set out in greater detail in an official document, namely a statute on VKO coordination (Vozdushno-Kosmicheskaya Oborona, August 2013).

The problems and challenges facing the VKO are therefore much more complex than the re-equipping and modernization of its structures with state-of-the-art systems such as the much vaunted S-500 air defense system, which the defense ministry claims will begin entering service by 2017. These problems are organizational and systemic in their very nature, as both Tarnayev and Barvinenko suggest. However, in addition to issues related to organization or equipment, brigade commanders also highlight ongoing personnel setbacks. Konstantin Ogiyenko, an air defense brigade commander in the Air Defense and Ballistic Missile Defense Command of the VKO, offered extensive comments on these personnel issues in an interview with Ekho Moskvy (August 16).

Ogiyenko explained that in 2013 the last graduation of lieutenants will occur, meaning that for three years there will be no new lieutenants. He protested, “And imagine not having lieutenants in the primary positions for three years and having this drop occur. After they leave, who will teach them? This, of course, is difficult for us. And how will training be conducted? But [now] they are arriving and entering the school. They will study five years. And how will we influence training here? A year after the graduation of the lieutenants, we will send reviews to the school about them and express our own wishes about what they should pay more attention to, and about what kind of training they should receive, and so on. Now in our branch of the armed forces we have taken on the Mozhaysk academy, the Tver academy and the Yaroslavl school. So it is simpler for us. We are working with them directly” (Ekho Moskvy, August 16).

To reinforce his complaint about staffing in his brigade, Ogiyenko provided some numbers on graduates from higher educational establishments entering service. In 2010, the brigade received 94 graduates, or lieutenants, among which four were discharged at their own request; in 2011, 63 lieutenants arrived and seven were discharged. In 2012, the brigade received 58 graduates and no one was discharged, while this year the number dropped to 50 and next year it will reach zero (Ekho Moskvy, August 16).

At a time when the political-military leadership in Moscow is expressing concern about the potential air-based threats to the country, mainly in reference to Western-led operations in recent years, the new VKO is experiencing systemic problems that are likely to take considerable time and political will to resolve. These issues will add additional burdens to the already troubled effort to rearm by 2020, as well as present numerous opportunities for fresh revisions to the original VKO plans.