Russia’s Push to Complete Nord Stream Two

Russia’s Push to Complete Nord Stream Two

While the United States struggles with the coronavirus pandemic, Russia has deployed two pipe-laying vessels to the Baltic Sea in a suspected attempt to complete the Nord Stream Two natural gas pipeline. On May 12, Russian pipe layer Akademik Cherskiy arrived at the German port of Mukran, on Rügen Island, where the Nord Stream Two logistics hub is located (Marinetraffic.com, accessed May 13). The ship joined the Russian pipeline crane vessel Fortuna, which is equipped with the necessary pipe-welding gear that the Akademik Cherskiy lacks. If allowed to work in combination, the two vessels are capable of laying the remaining 100 miles of Nord Stream Two pipeline from Denmark’s Bornholm Island to the German coast.

Since last December, when the Swiss Allseas Group S.A. suspended its Nord Stream Two construction works under threat of new US sanctions, the Kremlin has been seeking alternatives to complete the pipeline project (Allseas, December 21, 2019). The Akademik Cherskiy, Gazprom’s only pipe-laying ship that has a dynamic positioning system (as required by the Danish Energy Agency), has topped the list—working alone or in combination with a pipe-laying barge (TASS, December 27, 2019; DEA, October 30, 2019).

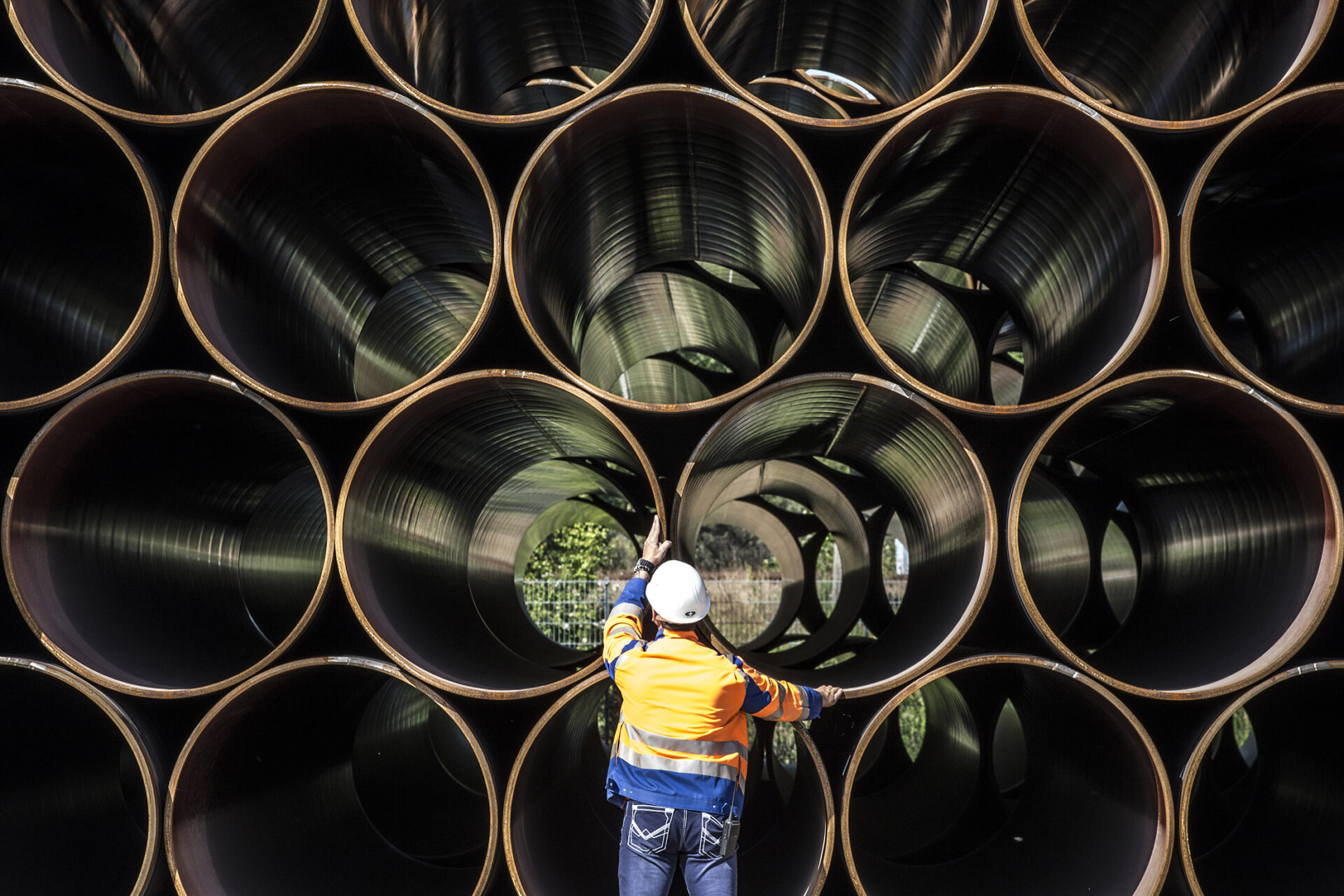

The Gazprom-owned ship, however, is only equipped for laying pipes up to 32 inches in diameter, while the twin Nord Stream Two pipes are wider, 48 inches in diameter. Thus, the pipe-laying barge Fortuna will have to be physically attached to the Akademik Cherskiy to complete the job (Gazeta.ru, May 7). Such a solution carries its own technological and environmental risks, particularly if the Fortuna needs to be anchored near World War II–era munitions dumps in the Baltic Sea; thus its involvement will have to be approved by the Danish Energy Agency (Europe’s Edge, February 19; Helcom.fi, 2013).

Both vessels and their owners, Russia’s energy giant Gazprom and subsea construction company MRTS, respectively, risk US sanctions as soon as they engage in Nord Stream Two pipe-laying. The US Department of State, in coordination with the US Treasury Department, is obliged to submit regular reports to Congress about all vessels engaged in pipe-laying for the construction of the Nord Stream Two pipeline project, as well as any foreign persons who have knowingly sold, leased or provided those vessels for the construction of such a project (Congress.gov, December 20, 2019, p. 1103).

The next report to Congress is due by May 20. If the two Russian vessels have started preparations for resuming Nord Stream Two construction, the report will have to include that information. US sanctions against Gazprom would have a detrimental effect on Russia’s energy sector, natural gas exports and international projects. But the authorities in Moscow do not seem to believe that Washington would sanction Russia’s largest gas company. Alternatively, the Kremlin is calculating that brisk construction of the remaining 100 miles of pipeline while Washington is preoccupied by the pandemic and the struggling national economy would take the US government by surprise, leaving it with no time to react.

Russian officials have publicly expressed confidence that blocking the construction of the Nord Stream Two gas pipeline is not a US government priority, “especially considering the new challenges Washington and Moscow are trying to jointly answer,” according to the chairperson of the State Duma Energy Committee, Pavel Zavalny. “I think it would be right if America abandoned these ineffective, wrong sanctions,” Zavalny said last month (Interfax, April 22). He also argued that since the pandemic shrank the demand for energy and brought energy prices down, it would be simply economically unprofitable for the US to supply Europe with liquefied natural gas (LNG). This statement reiterated a favorite line in Russian disinformation that the US is opposed to Nord Stream Two only because it wants to sell more LNG in Europe (Polygraph.info, May 12, 2019).

Zavalny’s statement alluded not only to Washington’s struggle with the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing economic crisis, but also to recent cooperation between Washington and Moscow on stabilizing plummeting oil prices, which was followed by the new OPEC+ agreement in April (Lenta.ru, April 12). The Kremlin capitalized on the fact that US President Donald Trump was the one who initiated the call with Russian President Vladimir Putin to help smooth Russia’s spat with Saudi Arabia over oil production quotas (Kremlin.ru, March 30). The Russian press widely publicized President Trump’s praise for the deal, which he said “would save hundreds of thousands of energy jobs in the United States” (Twitter.com/realDonaldTrump, April 12). Now Moscow evidently expects a quid pro quo—just as Russia helped with propping up oil prices to save American jobs, it now wants the US government to close its eyes and forget about the sanctions law until the pipeline is built.

The Russian operation to bring the Akademik Cherskiy across the globe from Nakhodka in the Far East, where it was involved in the Sakhalin-3 oil pipeline project, to the Baltic Sea, was a long and complicated endeavor (see Hot Issues, March 31). The ship left Nakhodka on February 10; but instead of heading directly toward Danish territorial waters, it sailed to Singapore, changed course to Sri Lanka, skipped the Port of Suez and circled the African continent to Las Palmas on the Canary Islands. The next stated course to Egypt’s Port Said was also changed and, on April 28, the Akademik Cherskiy passed through the English Channel into the North Sea (Gazeta.ru, May 7; TASS, May 1).

According to observers, the Cherskiy’s wavering route and often-changing direction was an apparent attempt to deceive observers and conceal the ship’s final destination to avoid sanctions or a ban on entering foreign territorial waters. Significantly, Russian navy ships or civilian support vessels accompanied the pipe layer throughout its journey. At different times, the Cherskiy was guarded by the large anti-submarine ship of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Vinogradov, the patrol ship of the Baltic Fleet Yaroslav the Wise, the rescue tugboat of the Northern Fleet Nikolay Chiker, and the sea tanker Akademik Pashin (Gazeta.ru, May 7). The engagement of Russian military ships in the Akademik Cherskiy’s convoluted journey to the Baltic Sea underscores that finishing Nord Stream Two construction remains an imperative for the Kremlin. The two Russian vessels may try to start construction works immediately, before the closures in the eastern Baltic Sea in July and August to allow cod to spawn (Ices.dk, May 2019). Satellite images of the port of Mukran taken on May 10 show Nord Stream Two pipe segments already moved to a pier adjacent to the Russian vessel Fortuna (Bloomberg, May 13).