Russo-Japanese Rapprochement Moves Forward

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 35

By:

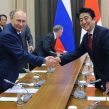

Despite the mounting ferocity of Sino-Japanese rhetoric, China’s partner Russia is moving forward on normalizing its ties with Japan. Indeed, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe met with Russian President Vladimir Putin at Sochi on February 8, and Putin has accepted an invitation to visit Tokyo in May (https://eng.kremlin.ru/transcripts/6627; Kyodo World Service, January 28). Moreover, on Friday, January 31, in Tokyo, Russia and Japan officially began the first round of talks on a bilateral peace treaty to formally close the World War II chapter of their relationship. The Tokyo meeting included delegations led by Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Igor Morgulov and his Japanese counterpart, Shinsuke Sugiyama, and their consultations focused on the historical aspect of the two countries’ unresolved conflict. As they continue over the following months, both sides pledge that these negotiations will include a serious discussion of the disputed Kurile Islands as well (RIA Novosti, January 31).

The bilateral talks are moving forward despite the fact that the overall environment in Asia is becoming ever more inauspicious as Chinese attacks on Japan grow and Japanese resistance stiffens. But those are not the only obstacles. For example, the Japanese government published a detailed account of all the scrambling missions it had to take against foreign aircraft—many of which were Russian—in April–December 2013 (Japanese Ministry of Defense, January 21). Such revelations certainly impede efforts to improve bilateral relations. But Moscow has made no formal reply and, indeed, its press has been relatively quiet on Japanese issues.

Russia’s Foreign Minister Segei Lavrov, on the other hand, has to deal with these issues in his official capacity. Yet, his response to what appeared to China as an outrageous provocation, namely Abe’s visit to the Yasukuni Shrine in late 2013, was relatively restrained. Lavrov said that Russia felt Abe’s visit was a misstep that does not facilitate bilateral normalization (Xinhua, December 30, 2013). And later, he went on to reiterate on two separate occasions during the same press conference that all contested territorial issues in the Pacific, including the root issue that is now roiling Sino-Japanese relations—the Senkaku or Diayoutai Islands—must be solved by peaceful means on the basis of the United Nations Charter, which formalized the end of World War II (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, January 24). In 2010, then-presidents Hu Jintao of China and Dmitry Medvedev of Russian formally agreed to support each other’s territorial claims against Japan regarding Pacific islands—disputed claims dating back to the Second World War. Thus, Lavrov’s tepid statement that he delivered at the end of January 2014 can hardly be expected to win any friends or influence in Beijing.

Undoubtedly China, which can ill-afford discord with Russia right now, is more than a little upset; but it has held its fire for now. In Chinese press reports, the official media claims that Russia stands by China against the “rebirth of Japanese militarism” (Wen Wei Po, January 22). But Moscow’s evident rapprochement with Tokyo was, at least in part, brought about by Beijing’s own regional actions. As many analysts have noted, China’s overall belligerent actions and talk have alarmed Russia, Japan, South Korea, India, Vietnam and India, not to mention the United States (see China Brief, September 12, 2013). So it is hardly surprising that Moscow and Tokyo are currently cozying up to each other.

Apart from the general stridency of Chinese claims and its unilateral imposition of an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the North Pacific (see China Brief, December 5, 2013), China has undertaken specific actions that threaten both Moscow’s and Tokyo’s interests. In mid-2012, a Chinese icebreaker, the Snow Dragon, made a historic, three-month expedition to the Arctic and sailed into the Sea of Okhotsk (Xinhua, September 27, 2012). The vessel’s route probably contributed to Russia’s response of declaring military exercises in the Far East to coincide with its voyage (https://www.mod.go.jp/e/publ/w_paper/pdf/2013/12_Part1_Chapter1_Sec4.pdf). As the Snow Dragon passed between Sakhalin Island and Japan, the Russian military decided to test its anti-ship missiles on Sakhalin. Next year, in summer 2013, after their joint exercises with the Russian Navy (see China Brief, September 12, 2013), Chinese naval vessels, sailed into the Sea of Okhotsk, cruised south of Sakhalin, through the Kurile island chain, and eventually circumnavigated Japan, thus entering into the Sea of Japan, hitherto thought of as a Russo-Japanese lake. Though the Chinese naval tour did not result in any dangerous incidents with regional neighbors, nonetheless the Russian government immediately launched a snap inspection exercise personally supervised by President Putin that was the largest sea and land exercise in Russia’s Eastern Military District since the end of the Cold War (mil.ru, July 13, 2013; see EDM, July 23, 2013; https://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2013/11/27-gang-two-russia-japan-make-play-pacific-hill).

Such incidents notwithstanding, Russia is unlikely to turn anti-Chinese for now and would like to forge a relationship where it and China can work together with Japan—for example, on future military exercises. But Moscow also refuses to be pressured by Beijing’s unilateral actions and will continue to hedge against overweening Chinese policies in Northeast Asia by reaching out to other regional neighbors. The Russo-Japanese rapprochement is but the most recent overt example of this policy course.