Scandal Exposes Technocracy, Nepotism, and Control Among PRC Elite

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 12

By:

Executive Summary:

- Elite privilege and lack of transparent checks and balances mean that corruption scandals are a feature of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) system of governance. As Beijing seeks to manage rising public discontent and technocratic continuity, it faces a delicate balancing act between providing symbolic accountability while ensuring elite preservation.

- A recent scandal involving a medical intern recently sparked public outrage when it transpired that her parents likely abused their powerful positions to engineer an impressive but unlikely career trajectory. The scandal exposed mechanisms through which elite families in the PRC navigate and dominate key institutional pathways.

- The episode has unfolded with a surprising degree of media tolerance from Beijing, with light-touch censorship suggesting that the Party may seek to leverage the incident to restructure entrenched power networks within the healthcare sector and academia.

- The official response—revoking the intern’s medical license—was largely successful in appeasing growing public frustration over elite privilege, indicating a sophisticated playbook for stability maintenance.

On April 18, an open letter circulated online accusing Dr. Xiao Fei (肖飞), a thoracic surgeon at the China–Japan Friendship Hospital (中日友好医院), of engaging in extramarital affairs with multiple colleagues (InnoMD, April 28). Public accusations by spouses targeting disloyal partners are not uncommon on the internet within the People’s Republic of China (PRC); however, by April 28, the focus of online discourse had shifted. Attention turned away from Dr. Xiao’s personal misconduct to focus on one of the named mistresses, Dong Xiying (董袭莹), and the circumstances surrounding her rapid career advancement within the country’s healthcare bureaucracy.

Investigative research suggests Dong Xiying has been able to engineer a meteoric rise in part by leaning on the connections and questionable behavior of her powerful parents. This story offers a glimpse into how a technocratic elite—what some call a “scholar-official clan” (学阀)—can exert influence across seemingly unrelated sectors within the PRC’s institutional ecosystem (China Digital Times [CDT], accessed June 18). It also shines a light on how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) balances between an opaque system that often relies on informal patronage networks and a discontented public that calls for accountability for perceived injustices.

Elite Networks Helped Dong Cheat the System

According to publicly available information, Dong is currently a licensed physician at the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (中国医学科学院肿瘤医院) (Baidu Health, accessed May 1). At the time of the affair, however, she was an intern at the hospital where Xiao worked. Her attainment of a medical doctorate from Peking Union Medical College (北京协和医学院; PUMC), widely regarded as one of the most prestigious medical institutions in the country, and possibly in all of Asia, has been the focus of public scrutiny.

Unlike the conventional pathway in the PRC, where medical education spans 11–12 years from undergraduate study to clinical qualification, Dong earned her medical doctorate in just four years through a special track known as the “4+4” program. Officially titled the “Pilot Reform Class for Clinical Medical Training” (临床医学专业培养模式改革试点班), this program, according to PUMC’s website, was established to “respond to the spirit of the National Undergraduate Education Conference in the New Era … targeting outstanding undergraduate students with … high potential to become exceptional physicians” (响应新时代全国高等学校本科教育工作会议精神 … 招收 … 具备成为卓越医生潜质的优秀本科生) (PUMC, accessed May 2). Entry requirements for the program are stringent, requiring a high number of undergraduate class credits from a top 50 global university (or, in the case of U.S. liberal arts colleges, a top 10 national university). Each applicant also must secure recommendations from at least two associate professors or above in medical-related disciplines (PUMC, accessed May 2).

Dong holds an undergraduate degree in economics from Barnard College in New York. Based on publicly stated admissions criteria, she would not appear to meet the entry requirements for the “4+4” program. More controversially, during her time as a student and intern, Dong is credited with authoring or co-authoring a total of 11 academic papers—including her dissertation—spanning disciplines as varied as orthopedics, gynecology, radiology, polymer physics and chemistry, and materials science (YiCai, April 30; GitHub, accessed May 2). Particularly notable is her position as lead author on a paper titled “Clinical Practice Guideline of Bladder Cancer,” a role typically reserved for seasoned clinicians (Sohu, April 30). Dong’s unusual resumé has led to widespread skepticism, leading CNKI, the PRC’s largest academic database, to retract her doctoral dissertation.

Figure 1: Dong Xiying Thanks her Supportive Family in her Dissertation

(Source: Github)

As news of the scandal broke, netizens uncovered information about Dong Xiying’s family that added to criticisms of corruption and a lack of fairness within the PRC. Dong Xiying’s mother, Mi Zhenli (米振莉), is deeply embedded in the PRC’s materials science establishment, judging from her academic publications and patents (Chinalco, August 19, 2024; USTB, accessed May 3). She currently serves as a deputy director of both the National Engineering Research Center for Advanced Rolling and Intelligent Manufacturing (高效轧制与智能制造国家工程研究中心) and the Institute of Engineering Technology at the University of Science and Technology Beijing (北京科技大学; USTB) (Baidu Baike, April 30). Critiques of Dong Xiying’s family ties have focused substantial textual and technical overlap between sections of Dong Xiying’s doctoral dissertation and a patent registered by several professors at USTB, where her mother works (Yangcheng Evening News, May 1). This discovery has fueled speculation that Mi Zhenli may have played a direct role in contributing to Dong’s dissertation.

Dong Xiying’s father, Dong Xiaohui (董晓辉), holds multiple senior roles within the state-owned metals conglomerate system. He currently serves as a board member, general manager, and deputy Party secretary of the China Metallurgical Construction Research Institute (中冶建筑研究总院; MCC), a subsidiary of China Minmetals Corporation (中国五矿集团) (AiQicha, accessed May 2; MCC, accessed May 2). He also concurrently holds the position of general manager at Chalco Advanced Material (中铝新材料), a wholly owned subsidiary of the Aluminum Corporation of China (中铝集团; Chinalco), the world’s largest aluminium producer (AiQicha, accessed May 2). In 2018, Dong transferred the largest shareholding of a private equity firm he owned called Beijing Junxiao Equity Investment (北京君晓股权投资中心) to his daughter (AiQicha, accessed May 2).

Dong Xiaohui has connections to the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, the very institution where his daughter is now employed. Public records reveal that Dong Xiaohui personally attended both the groundbreaking and topping-out ceremonies for the construction of the hospital in 2017. At the time, according to corporate registration records, he served as board director and general manager of Beijing Yuanda Engineering Management Consulting (北京远达国际工程管理咨询), a wholly owned subsidiary of the MCC, where he currently serves as a board member (AiQicha, accessed May 3). During his tenure, Yuanda secured a number of contracts related to hospital construction and managing medical equipment procurement tenders (Sohu, December 26, 2017; May 2; Xunbiaobao, accessed May 3).

Information concerning Dong Xiaohui’s father (Dong Xiying’s grandfather) has deepened suspicions about Dong Xiying’s career trajectory. Dong Baowei (董宝玮), according to online sleuths, is a medical specialist and former director of the ultrasound department at the prestigious PLA General Hospital (a.k.a. 301 Hospital) in Beijing. Authorities, however, have sought to quell these rumors. On May 1, an official statement from Weibo’s administrators refuted suggestions that Dong Baowei and Dong Xiaohui were related (Tencent News, May 2). The refutation did not provide any alternative explanation of Dong Xiying’s family ties, however. Authorities also refuted a separate rumor suggesting that Mi Zhenli was the daughter of a foreign member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering (Weibo Trends, accessed June 19).

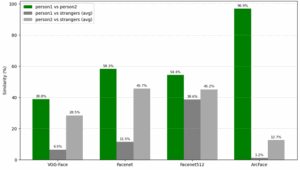

To assess the plausibility of a familial link between Dong Xiaohui and Dong Baowei, I conducted a facial similarity analysis using four deep learning-based face recognition models on publicly available official ID photographs of Dong Xiaohui and Dong Baowei. The results strongly suggest that the two men are related, contrary to official denials. The results of the experiment are summarized in the following table and figure, and the codes can be found in the appendix below.

Table 1: Model results on Whether Dong Xiaohui and Dong Baowei are the Same Person

| Model | Same Person? |

| ArcFace | True |

| VGG-Face | True |

| Facenet | False |

| Facenet512 | False |

(Source: Author)

Figure 2: Similarity Comparison Across DeepFace Models

(Source: Author)

All four facial recognition models consistently found that the similarity between Dong Xiaohui and Dong Baowei was significantly higher than their respective similarities to unrelated control subjects the models were also tested on. Among the models, Facenet and Facenet512 returned similarity scores for the two men’s photographs in the 54–58 percent range. According to experts who blog about facial recognition on Github, this range is often interpreted as indicating biological resemblance; that is, suggestive of a familial relationship (National Institute of Standard and Technology, September 11, 2019; Github, accessed June 19). The ArcFace model, by contrast, tends to classify first-degree relatives with near-identical facial features as the same individual due to the model’s high sensitivity. In this case, it returned a score approaching 100 percent, suggesting an extremely close resemblance. The fourth model, VGG-Face, also returned a positive score that, despite being more moderate than the other models’ scores, was still above the usual threshold for unrelated individuals. Taken together, the combined results show a high probability of a first-degree familial relationship between the two men. If so, Dong Xiaohui’s institutional ties may have been established well before his tenure at Yuanda, and perhaps were facilitated by pre-existing familial connections within the PRC’s medical establishment.

Beijing’s Crisis Management Playbook

The exposure of such a privileged family’s apparent ability to covertly leverage resources across two seemingly unrelated sectors—medicine and heavy industry—has triggered public anger. Witnessing how an entrenched academic elite family can bypass fierce competition to secure lucrative positions for their offspring is likely to provoke widespread resentment—especially among young people, many of whom face the dual pressures of “involution” (内卷) and the grim reality of “graduation equals unemployment” (毕业即失业). Beijing is eager to suppress that anger, which could easily fuel a form of passive resistance—a phenomenon known as “lying flat” (躺平) (People’s Daily, November 15, 2022). Popular among disillusioned university graduates, “lying flat” entails opting out of societal expectations by drastically curbing consumption, refusing to work, and rejecting marriage.

The latest scandal paints a picture of a governance system where outcomes are markedly different from the regime’s ideal of equality and Xi Jinping’s narrative of a “China dream” (中国梦). The picture that emerges instead is one that chimes with phrases like “dragons beget dragons, phoenixes beget phoenixes” (龙生龙,凤生凤), which children in the PRC are taught to characterize the injustices of the “old society” (旧社会)—particularly the infamous “Four Great Families” of the Republican era: the Chiangs, Soongs, Kungs, and Chens (蒋宋孔陈四大家族), who have long been portrayed in public education as cautionary tales (Baidu Baike, May 20). In this way, the Dong family scandal does more than expose an alternate path to success that remains inaccessible to ordinary citizens—it calls into question the validity of the formula that underpins the CCP’s approach to governance.

Beijing clearly recognizes the crisis of credibility it faces as a result of such scandals. In the case of Dong Xiying, the government responded with a series of measures aimed at salvaging its image and restoring public trust (People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Data Center, May 19). Unlike in many past cases, authorities did not censor online discussions or complaints. Instead, they even allowed some rumors to circulate. This strategy created an illusion of responsiveness, encouraging the public to believe that their outrage could compel the government to act seriously and punish those involved. Beijing’s official denials of any familial ties between Dong Xiaohui and Dong Baowei, as well as between Dong Xiying’s mother, Mi Zhenli, and a foreign academician, formed a second stage of this playbook (Jimu News, May 2). The denials aimed to minimize the scandal’s scope, framing it not as the exposure of a powerful hereditary “scholar-official clan” but merely as an isolated case of a father helping his daughter circumvent university admissions rules. Crucially, the intended end-state informed the state’s response, rather than any relationship its claims had with the truth. The goal was instead for the regime’s myth of “equality” to remain nominally intact.

The final stage of the official response was to announce an investigation that found Dong Xiying guilty of academic fraud, falsified grades, and involvement in an irregular admissions process. Her medical degree and license were revoked (China News, May 15). With this apparent fait accompli, the government asserted that the public was largely satisfied with the outcome—though neither Dong Xiying’s father nor PUMC faced punishment (People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Data Center, May 19). This selective accountability reinforced the message that the system remains fair while avoiding any real disruption to elite networks.

Beijing has constructed an effective playbook for managing online discourse by maintaining so-called harmony and dampening criticism. In the Dong Xiying case, this playbook was almost a complete success. Discontent continued after official attempts to dole out justice on minimally disruptive terms, but ultimately the regime was able to engineer more positive views of the regime by capitalizing on the arrival of a fresh news cycle. As conflict erupted south of the border between India and Pakistan, stories emerged of PRC military technology helping Pakistan to down Indian fighter jets. These stories spread rapidly across screens, flooding digital spaces with nationalist pride. The dominant tone of online discourse shifted from skepticism of the government to renewed confidence in the state’s military and technological prowess.

Conclusion

The Dong Xiying affair is indicative of the balance Xi Jinping intends to strike in his quest to achieve national rejuvenation via Chinese-style modernization. In this instance, Beijing was able to capitalize on external developments to reinforce regime stability and quell public dissatisfaction that had been mounting for several months by pointing to evidence of material progress in the country’s technological development. As economic problems persist in the months and years ahead, Xi increasingly is set to pin the nation’s hopes on ever-greater technological advances to underwrite the legitimacy of his regime. His ability to maintain this fine balance is now a key determinant of the PRC’s fortunes.