Sino-Pakistani Relations Reach New Level After Zadari’s Visit

Publication: China Brief Volume: 8 Issue: 24

By:

China and Pakistan have vowed to push their friendship to new heights (Daily Times, October 17) as the two nations are now exploring new summits in the economic partnership that they have forged since Asif Zardari moved into the Aiwan-i-Sadr (President’s House). As a successful businessman, President Zardari is expected to draw Beijing into an enduring partnership based on trade and investment and to deepen Beijing’s stakes in Pakistan’s national economy and thereby enhance its stability. After years of steady growth of over 6 percent a year, Pakistan has recently seen its economy hit a rough patch. It has found itself drained of liquidity (i.e., cash capital) to bridge its ever-widening trade deficit. Although the country’s export economy is flourishing, it is still susceptible to the volatile commodity market, especially the oil imports which soak up the bulk of its foreign exchange reserves—its oil import bill for 2008 ran up to $11 billion (The Dawn, November 21).

Pakistan’s Macroeconomy

With an anticipated surge in its trade economy, the energy costs for Pakistan are bound to shoot still higher. This means an even wider trade deficit. The projected volume of Pakistan’s bilateral trade in 2008-9 is valued at $56 billion, which is almost 36 percent of its GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of $146 billion. If the increase in the projected trade volume materializes into reality, it will leave Pakistan with a deficit of $14 billion from an imbalance between its exports of $21.3 billion and imports of $35 billion (Daily Times, December 12). This yawning gap will remain unabridged even after it eats up the last dollar in the country’s foreign exchange reserves that have already dwindled to $8 billion in 2008 from a high of $16 billion a year before. Worse still, the trade deficit, directly or indirectly, has punched a deep hole in a national budget that already stands far away from being balanced. As a result, the gap between income and spending has widened to 6.7 percent of the GDP (Bloomberg, June 12).

It is this macroeconomic straitjacket that worries President Zardari. Pakistan needs a partner who can help the country out of this menacing challenge, and this was exactly what went into planning Zadari’s state visit to China at the invitation of Chinese President Hu Jintao, on October 14-17. It has also become customary for every Pakistani leader to begin their term in office with the first call on the "all-weather friend." After his swearing-in as president in September, Zardari took a bit longer than his predecessors to pay a visit to Beijing, for which he caught flak from friends and foes alike (International Herald Tribune, October 13). What further enraged his detractors was his erstwhile private visit to Britain after assuming office as President, which he undertook to seek British intervention for a short-term loan from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) to meet the country’s cash needs. His detractors wanted him, instead, to choose Beijing as his first stop. The need for emergency assistance, however, hastened his visit to China where he wanted to rustle up urgent cash (between $500 million to $1.5 billion) to avert a default on immediate debt obligations (The Dawn, October 16). China, which sits on a mountain of $2 trillion in foreign currency reserves, obliged President Zardari with a soft (i.e., low-interest) loan of $500 million. In terms of long-term economic goals, President Zardari had the Planning Commission of Pakistan work out an economic charter that is charged with helping grow bilateral trade between Beijing and Islamabad, as well as in attracting Chinese investment (Business Recorder, September 26). On September 26, the Planning Commission, in consultation with Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan Lou Zhaohui, prepared the document, which intends to remove any infrastructural bottlenecks in the path of Chinese projects and guarantee their speedy execution (Business Recorder, September 26).

Trade and Investment

The completion of these projects is expected to put Pakistan’s trade economy in the fast lane. As of 2008, two-way trade between China and Pakistan has already risen to $7 billion from a meager $2 billion in 2003. It is now set to grow to $15 billion by 2010 (The Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), December 12). In parallel, informal trade between the two countries also runs into the billions of dollars. This off-the-books trade is part of the reason why both countries have signed the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) that is now in effect. The FTA will allow both nations more preferential terms of trade than permissible as members of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Growth in the investment sector is running along a similar trajectory. In fact, China has already emerged as the largest investor in Pakistan, with its investment portfolio poised to swell to $15 billion by 2012. During President Zardari’s visit, Chinese companies pledged to invest $5 billion in his country. In addition, his persuasion for the faster growth in trade and investment yielded 12 major agreements and memoranda of understanding (MOUs) (The Dawn, October 16) to enhance economic collaboration in such sectors as energy, minerals, infrastructural development, and telecom.

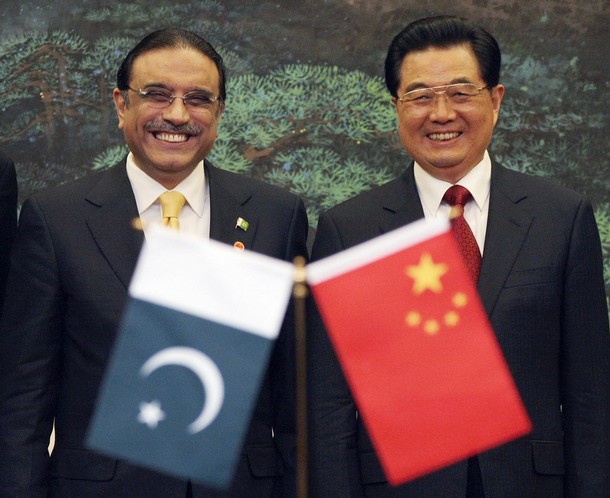

The significance of these pacts was evident on October 16 at a staged ceremony held at the Great Hall of the People that was accompanied by pomp and circumstance, while Chinese President Hu and President Zardari hung around to cheer each other on. Earlier, in a one-on-one meeting, President Hu spent an hour with President Zardari to discuss the future shape of their bilateral relations. Both "reached broad agreement on strengthening the China-Pakistan strategic partnership of cooperation and on international and regional issues of mutual interest under the new circumstances" (Daily Times, October 17). Later, the two men were joined by their aides for another two-hour session. President Hu finally capped the day with a state banquet to honor President Zardari. The hallmark of the banquet was the two leaders’ speeches that noted how each nation is special to the other, and Pakistan’s affirmation of the "one China" policy.

On the day following the glittering signing ceremony and sumptuous banquet, 200 top Chinese corporate executives descended on the State Guest House in Beijing, where President Zardari was staying, to further discuss the avenues of trade and investment in Pakistan. Zardari charmed them with preferential terms of trade and investment that he has now institutionalized in the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) under the FTA. All products manufactured in these zones will be exempt from trade tariff.

Energy and Mineral Production

President Zardari made a special headway in advancing Chinese collaboration in the energy production sector. Pakistan has long sought Chinese investment in the development of its subsoil resources, such as coal, oil and natural gas in Sind and Balochistan. Thar coalfield in Sind boasts one of the world’s largest reserves of 185 billion tons and has a market value that runs into the trillions of dollars (Jang, October 17). Similarly, the net value of metallic resources at Rekodiq, Chaghi, Balochistan, is estimated at $65 billion (The Dawn, September 26). Besides, Pakistan sits on 30 trillion cubic feet of untapped natural gas reserves (Jang, December 12), which is also valued in trillions of dollars. To finance these projects, China and Pakistan have already established a joint venture company with an initial Chinese capital investment of $500 million.

Sino-Pakistani Relations and South Asia

The close economic cooperation between China and Pakistan drew cheers from all of their South Asian neighbors, except for India that has been instinctively wary of their alliance. Its outlook has, nevertheless, begun to change since a dramatic growth in Sino-Indian economic relations has overtaken those of China-Pakistan. As of 2008, Sino-Indian trade has reached $40 billion a year. It is now set to grow to $60 billion by 2010 [1].

To balance its strategic interests with economic ones, China has steadily served as a moderating influence on Pakistan’s historically conditioned view of India. It is especially evident in Beijing’s softening of its hard line on the Kashmir dispute, to New Delhi’s satisfaction. What is more, President Hu volunteered to mediate between India and Pakistan to help resolve this issue. China has since been advising Pakistan to seek a negotiated settlement of the Kashmir question (Jang, December 4). There are visible signs that Pakistani leaders are soaking up the advice and publicly articulating its merits (Jang, December 4).

Above all, China is cautious about its image as the world’s emerging great power, which impels it to conduct bi-national diplomacy in a way that does not conflict with its regional or global ambitions. The case in point is its most recent vote on December 10 at the United Nation Security Council, which led to the banning of Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JUD), a Pakistan-based charity, which is believed to be a front organization of the already outlawed terrorist group, Lashkar-i-Tayyaba, and which is accused of orchestrating the Mumbai attacks on November 26. Earlier, China has blocked the Security Council vote on the JUD three times due to an apparent lack of evidence. After terrorist strikes in Mumbai, however, China accepted the Indian case against the JUD and sided with the United States in the Security Council to vote yes on declaring it a terrorist organization. For its part, Pakistan did not demur and instead it cracked down on the JUD and shut down its operations.

In addition, China is going slow on Pakistan’s persistent pleas for an additional six nuclear power plants at the cost of $10 billion to meet its growing energy needs. China’s lukewarm response is meant in part to calm nuclear proliferation concerns in Washington. In equal measure, it intends to keep India unruffled. Yet China is fully supportive of Pakistan’s "right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy" [2]. Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi vowed to "continue extending nuclear cooperation to Pakistan" [3]. After swallowing Pakistan’s nuclear-capability in weapons production, India too has become resigned to Sino-Pakistani cooperation in nuclear energy. India’s External Minister Parnab Mukherjee publicly supported such cooperation, after China blessed the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal during President Hu’s visit to India in November 2006 [4].

Conclusion

Sino-Pakistani relations have outgrown their monolithic base in this traditional strategic partnership. They are now on the way to diversification into a mutually profitable economic relationship. Pakistan’s current leadership is far keener on the country’s economic security, which it wants to insure through trade and investment. In the near future, Chinese investment in Pakistan’s energy sector, mineral development and communications will multiply dramatically, further boosting the bilateral trade between the two countries. If Pakistan can overcome its energy shortfall, it is likely to emerge as the world’s sixth largest economy, rivaling Italy, taking into account Pakistan’s natural resources (i.e., coal and natural gas reserves), that are valued in the trillions of dollars. More importantly, Pakistan claims to possess combined on- and off-shore oil reserves of 3 trillion barrels. On top of that, Pakistan is a fast growing economy whose GDP doubled to $146 billion in 2001-2008 [5]. For its part, China is responding positively to the needs of a trusted ally that has become China’s watchtower along its restive western territory and along China’s borders with the Central Asian Muslim Republics. India will, however, continue to warily watch the two states as they explore new heights in their relationship.

Notes

1. "Perspective on India and China-India Relations-Speech by Mr Zhang Yan, Chinese Ambassador to India at Asia Society." Asia Society Hong Kong, June 18, 2008.

2. "Chinese Foreign Minister Visits Pakistan," https://english.mofcom.gov.cn/column/print.shtml?/bilateralexchanges/200804/200804055.

3. Op.cit.

4. Niaz, Tarique (2008), "The Turnaround in Sino-Indian Relations," https://www.japanfocus.org/products/details/2540.

5. For a detailed discussion, see: Niazi, Tarique (2008). "Globalization, Resource Conflicts and Social Violence in Asia." International Journal of Contemporary Sociology, 45(1): 177-202.