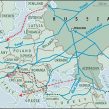

SOUTH STREAM GAS PROJECT DEFEATING NABUCCO BY DEFAULT

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 5 Issue: 42

By:

Gazprom’s blitzkrieg capture of five European Union member countries for its South Stream project, preempting the EU- and U.S.-backed Nabucco project, has shattered the credibility of Brussels’ and Washington’s energy security agendas. Country after country (excepting the lone holdout, Romania) have succumbed to the Kremlin-backed project because the Western one had neither gas resources, nor investment funds to offer after five years of efforts to obtain them.

By contrast, Gazprom comes up with the gas volumes, construction funds, and supplementary incentives in the form of collateral energy projects for the countries it targets. The deceptive nature of these offers is not always readily apparent to most of these countries; and when it becomes apparent, they see no realistic alternative materializing any time soon. Nabucco no longer looks plausible to them, given the continuing absence of Central Asian or Iranian gas for this project.

The countries joining South Stream (Italy, Greece, Serbia) and — even more to the point — those defecting from Nabucco in favor of South Stream (Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria) are motivated quite unsurprisingly by short-term thinking and opportunistic calculations on the economic level. They go for deals with Gazprom because their neighbors and potential competitors do so now; Brussels lacks the instruments of a common policy for energy projects, and Washington’s eminently sound cautionary advice comes without gas or investment credits and without top-level political support. Failing leadership on energy policy in Brussels and Washington gives “third-road” leaders, such as Hungary’s Socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany, an excuse to position themselves strategically between Russia and the West.

Hungary’s incorporation into South Stream means that Gazprom has secured the final leg of the transit route for Caspian gas to Europe and the markets along that route to Vienna. The outgoing and incoming presidents of Russia, Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, witnessed the February 28 signing ceremony in the Kremlin with barely disguised gloating, to Gyurcsany’s fawning.

Putin derided the Nabucco project: “You can build a pipeline or even two, three, or five. The question is what fuel you put through it and where do you get that fuel. If someone wants to dig into the ground and bury metal there in the form of a pipeline, please do so, we don’t object.” Sarcastically, Putin dismissed the notion of a competition between Nabucco and South Stream: “There can be no competition when one project has the gas and the other does not” (Interfax, February 28; Rossiiskaya gazeta, February 29).

Gyurcsany demonstrated that he had internalized the arguments for surrender. Citing Putin’s 2006 proposals to extend South Stream (at that time as the Blue Stream-Two version) to Hungary and on to Austria, Gyurcsany thanked profusely: “It is with satisfaction and gratitude that I see Russia doing everything it has promised to us. Hungary has realized that it had no alternative to cooperation with Russia.” He portrayed the choice of South Stream as a Hungarian national choice, in preference to Nabucco: “You were faster than the [Nabucco] project. And it is up to us to determine the tempo of implementing projects in our interest” (Interfax, Russia Television Channel One, February 28).

The Hungarian government’s alibi for choosing South Stream is that Hungary supports Nabucco also — an argument that ignores the two projects’ mutual incompatibility. But, in finally choosing South Stream, the government went to hyperbolic lengths, professing openness for an infinity of options. Its Moscow ambassador, Arpad Szekely, lobbying at home for South Stream, declared that Europe would need as many as 15 Russian gas pipelines and therefore Hungary’s choice of South Stream hardly makes a difference to the overall picture. In Moscow, Gyurcsany declared somewhat more modestly that Hungary would prefer to have two pipelines rather than one, or ideally three pipelines rather than two. The governmental Rossiiskaya gazeta (February 29) commented that the prime minister was “dreaming.”

In Brussels, the Russian ambassador to the European Union, Vladimir Chizhov, also felt able to deride the Nabucco project: “Nabucco is a classical example of an energy project that is being pushed to get rid of Russia. An empty pipe will bring no profits. What South Stream will be filled with is clear to us, but what Nabucco will be filled with, is clear to nobody” (Russia and CIS Business and Financial Newswire, February 29). What seems clear to Moscow is that South Stream — if actually built — would enable Gazprom to control Central Asian and even Iranian gas, for which the Nabucco project had been conceived.

The U.S. government made last-minute attempts to caution Hungary against rushing into the South Stream project. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Matt Bryza gave several interviews to Western media, which Hungary’s media replayed, during the week prior to the Moscow signing event. Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Fried published an article in Hungary’s leading newspaper, pointing to the economic disadvantages of South Stream to Hungary and the non-transparent endgame negotiations with Moscow (AP, Reuters, February 22, 25; Nepszabadsag, February 25, 28).

Hungary’s Fidesz opposition party and even the Free Democrats, junior partners to the Socialists in the government coalition, are criticizing the agreement with Moscow on South Stream and demanding a full-fledged parliamentary debate. However, due to Western failures to open access to Central Asian and Iranian gas, Russia’s South Stream is winning by default.

For now, the Kremlin and Gazprom are preempting supplies and markets against Nabucco and other Western-backed projects. Moscow’s offers are misleading, however. Gazprom will not, in fact, be able to provide the declared gas volumes for all of its existing and planned pipelines to Europe: Nord Stream, Yamal, the Ukrainian system, Blue Stream, and now South Stream. In the short-to-medium term, Gazprom itself faces gas supply shortfalls for Russia’s own rising internal consumption and its manifold export commitments.

Undoubtedly anticipating that situation, Gazprom seeks to accelerate pipeline construction in order to control European markets long-term through control of transportation and access, even if Gazprom’s own deliveries to Europe stagnate or decrease. At that stage, control of transportation — particularly in the southern corridor through South Stream — could position Russia to control the entry of pipeline-delivered gas to Europe from Central Asia and Iran. On top of its role as unwanted middleman, Gazprom would also become the gatekeeper of Europe’s southern corridor for energy supplies. Growing control of transport could extend Russia’s control of non-Russian gas en route to Europe and of the European markets, notwithstanding Gazprom’s own anticipated gas deficit.